Migrant crisis: What next for Germany's asylum seekers?

- Published

Germany has become the preferred destination for thousands of people reaching Europe in search of a better life.

Some 450,000 asylum seekers have entered Germany already this year and up to a million are expected in 2015 - by far the most in the EU.

The government in Berlin has broadly welcomed refugees, relaxing EU rules so that it no longer sends back Syrians to other EU countries.

But it introduced temporary border controls on Sunday after admitting that its capacity had been stretched to the limit.

How is Germany handling the arrivals?

Until now, the federal government has insisted it can cope with the high numbers of asylum seekers but wants the burden shared between EU countries.

Authorities have been giving assistance to new arrivals at stations in Munich and other German cities before taking them to reception centres.

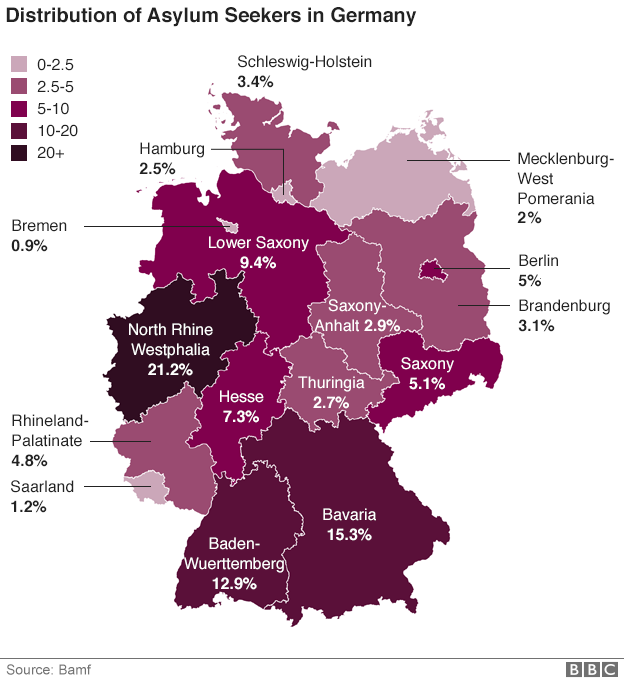

The "Koenigsteiner Key", external is used to distribute asylum seekers across Germany's 16 federal states, calculated according to their tax revenue and their population.

For example, North-Rhine Westphalia, Germany's most populous state, will be expected to take 21% of all asylum seekers, while Thuringia, the focus of several attacks on asylum accommodation, is set to receive under 3%.

What has changed?

With a huge build-up of asylum seekers in the Bavarian city of Munich, and reception centres apparently reaching capacity, authorities in affected states have been calling for the federal government in Berlin to do more.

Bavarian Interior Minister Joachim Herrmann told radio station Bayern 2 that stricter controls were needed because "many en route here are not really refugees".

"It's got about in the last few days that you are successful if everyone claims to be Syrian," he added.

This migrant family are being escorted to buses at Munich's main railway centre

The dispute has seen Chancellor Angela Merkel come under increasing pressure particularly from political allies in the Christian Social Union (CSU), which has ruled Bavaria, Germany's wealthiest state, for nearly 60 years. State Premier Horst Seehofer described the decision to open the borders as "a mistake that will occupy us for a long time".

German Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel told Tagesspiegel newspaper on Sunday, external that the problem was "not the number of refugees but the rapidity at which they arrived".

He said "Europe's inaction in the refugee crisis had driven Germany... to the limit of its capacity".

What is Germany doing about it?

The government ordered police to begin checking travel documents on Sunday from anyone entering from the southern frontier with Austria, and federal police set up roadblocks on motorway networks.

Rail services to Munich were affected by the changes, too.

Police officers have been conducting checks at the border between Germany and Austria

German Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere said the border controls would remain in place until further notice.

"The aim of this measure is to limit the current influx to Germany and to return to orderly entry procedures," he said.

"This is also urgently necessary for security reasons."

The move goes against the principle of the Schengen zone, external, which allows free movement between many European countries. However, the Schengen agreement does allow for temporary suspensions.

There have been warnings that the restrictions could make conditions worse for the thousands of migrants continuing to make the perilous journey across Europe to Germany.

"These measures will not create more order but only much more chaos," said Katrin Goering-Eckhardt, the parliamentary leader of the opposition Greens, according to Reuters.

But the government argues that the new measures will not affect the rights of refugees coming to Germany.

What does Germany want to happen?

The temporary border controls were introduced hours before an emergency meeting of European interior ministers and Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere said they were "a signal to Europe".

"Germany is facing up to its humanitarian responsibility, but the burdens connected with the large number of refugees must be distributed in solidarity," he said.

Germany wants other EU countries to commit to accepting more refugees and asylum seekers

EU ministers were to vote on a May 2015 plan to redistribute an initial 40,000 asylum seekers from Syria and Eritrea through mandatory quotas.

The EU has since raised the total number of people it seeks to share out through quotas to 160,000 asylum seekers across 23 EU states.

But Germany says this still is not enough.

Speaking in the German parliament last week, the vice chancellor described the plans as "a first step, if one wants to be polite".

"Or you could call it a drop in the ocean."

Who is given asylum in Germany?

An application for asylum is made at the reception centre on arrival, where personal details, fingerprints and photographs (for those over 14) are taken. A temporary permission to stay is granted.

The asylum seeker will then be invited to an interview to decide his or her case.

Migrants often face long waits at registration centres

The current average time from application to decision is 5.3 months, according to the German government.

If granted refugee status, a residence permit for three years will be granted. After this time a permanent residence permit can be applied for.

Germany designates all EU states plus Ghana, Senegal, Serbia, Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina as "safe countries of origin" - which means that asylum claims from nationals of these countries are likely to be rejected.

On 7 September the government announced that Kosovo, Albania and Montenegro would be added to this list.

What about accommodation and money?

Asylum seekers normally stay at reception centres for up to six weeks.

After that they are offered either communal accommodation, or housed individually, depending on the policy of the federal state.

Asylum seekers are initially put in reception centres such as this one in Baden-Wuerttemberg

People who are unable to support themselves financially "receive what they need for their day-to-day life", the German government says.

Support varies from state to state, but generally includes non-cash benefits covering food and accommodation costs, plus limited spending money.

After being in the country for three months, asylum seekers can apply for permission to start work, subject to various restrictions, external.

Anyone given a residence permit has unrestricted access to the labour market after four years.

Is this the first time Germany has dealt with such mass migration?

No - Germany has a long and complicated history of population movement.

After Germany's defeat in World War Two, millions of ethnic Germans were forced to leave areas of Poland, former Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania and Russia and resettle in West and East Germany.

Many ethnic Germans - such as these welcoming the Nazi annexation of Czech Sudetenland in 1938 - were expelled from eastern Europe after WW2

The booming economy of post-war West Germany required more workers, and huge numbers of "guest workers" arrived from Mediterranean countries such as Italy, Spain and - most significantly - Turkey.

Communist East Germany also took on temporary workers from "fraternal socialist countries", including North Vietnam, Cuba and Mozambique, although most returned after German reunification.

In 1991 the country enacted laws enabling Jews from the former Soviet Union to move to Germany - more than 200,000 Jewish people and their families, external immigrated in this way.

Around 350,000 people fleeing the Bosnian conflict were given temporary refuge in Germany in the 1990s, but most have since left, external.

In total, 20.3% of Germany's population now have "a migration background" - the term German officialdom uses to describe immigrants or their children.

But Germany's population is shrinking, due to its low birth rate, and it has been argued that it needs migrants to keep its economy going.