Migrant crisis: Finland's case against immigration

- Published

Finnish Prime Minister Juha Sipila has offered to let refugees live in his home

As EU member states consider whether to accept an increase in the number of asylum seekers they take in, particularly from Syria, they each face a vibrant internal discussion on how to respond to the challenges of immigration.

The BBC news website looks at the debate in Finland, where the difference between opinions is clearly defined, even within the government.

Last week, Finland's government said it was willing to double the number of refugees it was willing to accept this year, up to 30,000 from 15,000.

Only 3,600 applications were made last year - and so far this year, most applications were from Iraq and Somalia.

Some may even find themselves living with Prime Minister Juha Sipila, who said on Saturday that he was willing to give up one of his houses to migrants, external.

Thousands attended July's multiculturalism rally in Helsinki

Mr Sipila has said he feels Finland, a country of 5.5m people, should set an example to the rest of Europe on migration.

But his coalition partners are the anti-immigration Finns Party, who came second in April's election.

Integration problems?

Last month, Jussi Halla-aho, a Finns Party MEP, said some members of society were not integrating well enough, adding there was a risk "the society begins to play by the rules of the Muslim minority rather than expecting the minority to play by the rules of the society".

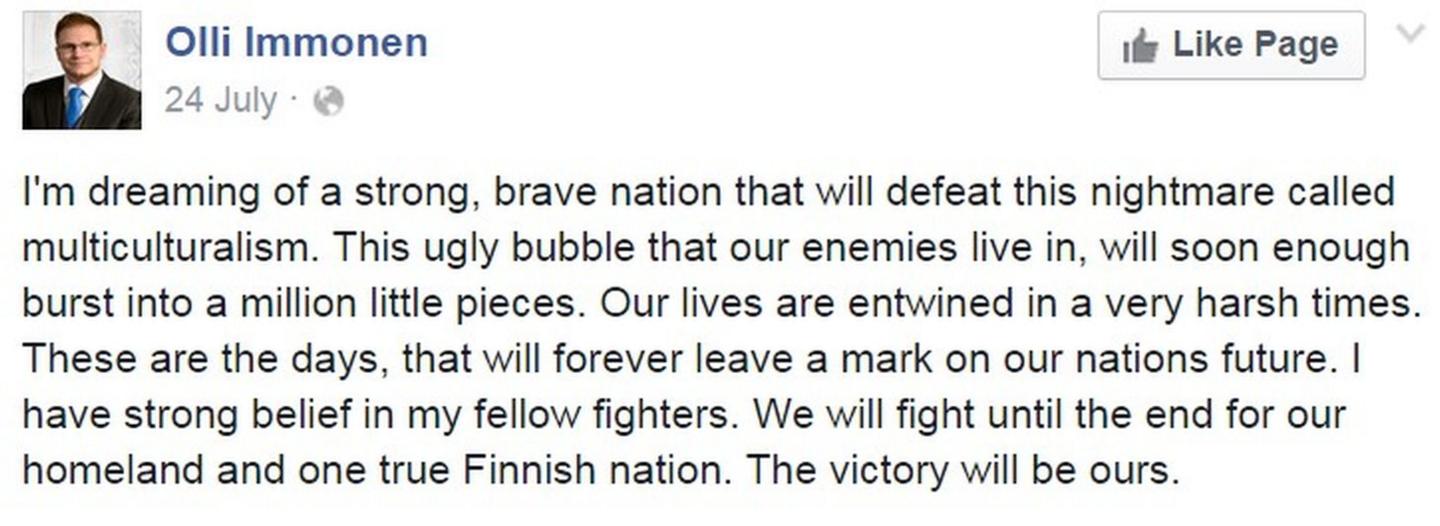

In July, Olli Immonen, one of the party's MPs, wrote of what he called "this nightmare called multiculturalism, external" on his Facebook page, adding: "We will fight until the end for our homeland and one true Finnish nation."

While the online responses to his comments were finely balanced between those who were for and against immigration, government colleagues were not supportive.

Finance Minister Alexander Stubb tweeted: "Multiculturalism is an asset. That's all I have to say., external" Mr Sipila wrote on Twitter that he wanted "to develop Finland as an open, linguistically and culturally international country".

Finns Party chief Timo Soini, who is Foreign Minister and Deputy Prime Minister, wrote on his blog last week that Christian and Yazidi minorities could be given priority as refugees.

But he came under heavy criticism and, in what Finnish newspapers noted was a significant swing, he changed course in an interview on Monday, external.

Concerns among right-wing politicians about the possible Islamisation of Finland, where 78% of the population belongs to the Lutheran Church, are reflected by sections of the public.

In August, before the new talks on migrant quotas, most Finns quoted in a survey said they would rather live next to an alcohol rehabilitation centre than a mosque, external, though no major polls have been conducted on people's opinions since then.

The Finnish Lutheran Church has seen a raft of resignations since members were asked to support refugees

On 2 September, the head of the Finnish Lutheran Church, Archbishop Kari Makinen, urged members to take in refugees.

Soon after, 196 people resigned from the Church in one day, compared to 80 people on a typical day.

"As the Finnish Church wants to help house IS fighters in Finland, I do not accept it," one person wrote on a website through which members can resign, external.

"The Church no longer defends Christian values, they support Islam's entry into Finland. Shame on you fools," wrote another.

Finland's economy has failed to come in from the cold for three years

Among the most common concerns held by Finns, external, the state broadcaster says, is that:

accepting more refugees leads to more crime

asylum seekers do not look to learn Finnish

reception centres are too expensive

These are concerns, it says, that are generally unfounded but widely shared.

Many anti-immigration bloggers concentrate on the financial burden of accepting more refugees. Finland's economy has slumped in recent years, having been in recession for three consecutive years, external.

In one protest against a new refugee centre last week, external, one demonstrator said: "Everything has been taken from the unemployed, the poor and the sick. But the coffers are empty.

"If these centres open, our taxes will go up."

Hate speech

On social media, there are many tales to be found, true or not, of attacks by immigrants. They are often widely shared, but we could not find confirmation of the attacks in Finnish media.

In one Facebook post written on 6 September, a man in western Finland detailed an alleged assault on two 12-year-old girls, purportedly by immigrants.

"These people are paperless asylum seekers whose backgrounds nobody in authority knows," the post said.

The post went on to be shared by more than 2,000 people and attracted many replies criticising immigrants.

Vitriolic comments are increasingly common. Last week, two large media groups closed comments on their websites because of what state broadcaster Yle called "a flood of hate speech and weak quality discussion, external".

"Particularly within the past year, the debate has become very sharp and aggressive, even including hate speech," Yle editorial director Atte Jaaskelainen said.

Marches in favour of multiculturalism have taken place in Finnish cities, with one - organised after Olli Immonen's comments in July - drew several thousand people in Helsinki.

In Finland's mainly neutral press, immigration is now rarely off the front pages. Articles concentrate largely on the plight of migrants and the work being done to help them.

Online, the voices speaking on behalf of immigration in Finland are more in evidence than those against.

On 12 September, a picnic to welcome migrants will be held in the capital, and has attracted more than 4,300 supporters on Facebook, external.

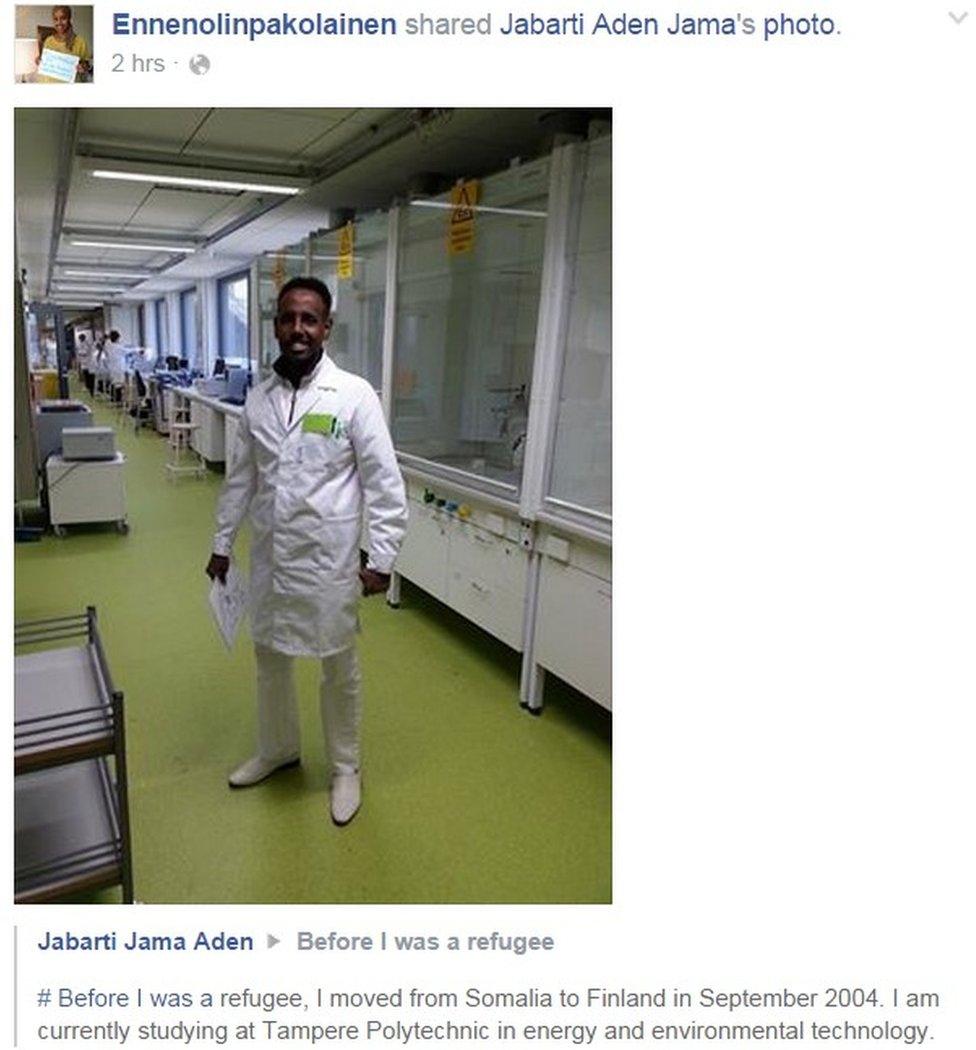

Meanwhile, another Facebook page named Ennenolin Pakolainen, external (I was a refugee before) has drawn more than 17,000 likes and compiles the stories of people who were refugees and what they are now doing in Finland - among them a trainee pilot, a nurse and a model.

Elsewhere, the Twitter account @TorillaOnTilaa, external brings together messages welcoming migrants - including many by Finnish national football team players.

"We are all equal, external," Fortuna Dusseldorf player Joel Pohjanpalo wrote.