Germany: Moral leader or misguided?

- Published

Migrants have received a warm welcome in Germany

Germany, for so long criticised as the author of austerity, is being lavished with praise.

Over the migrant crisis, it has demonstrated not just moral leadership, the German people have shown great acts of kindness to the refugees.

The German Chancellor Angela Merkel has described the German welcome as "breathtaking", external.

In not many European countries would you find refugees being met with the chant: "Say it loud. Say it clear. Refugees are welcome here.", external

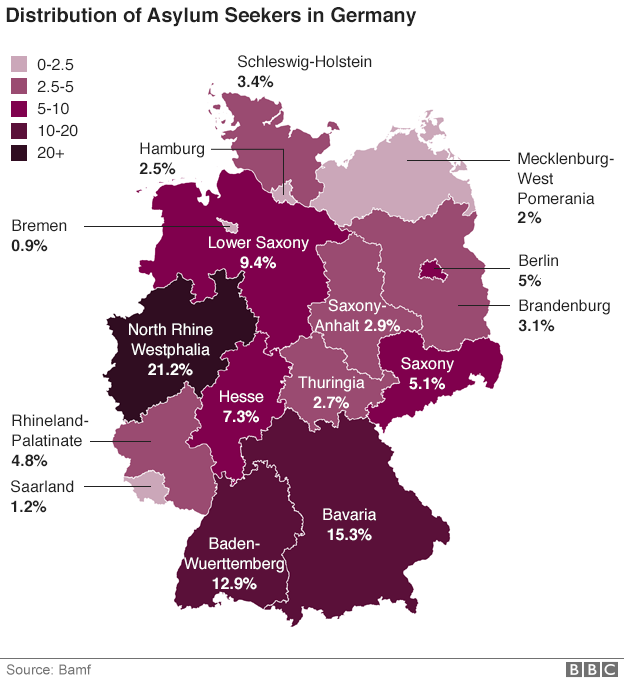

The scale of the German undertaking is enormous.

One state premier has now accepted publicly, external that the number of 800,000 refugees arriving in Germany "will need to be revised upwards".

The deputy chancellor is now talking, external of Germany taking in 500,000 refugees annually for several years.

The government in Berlin says that caring for the new arrivals will cost initially 6bn euros.

Defining issue

For a long time, Angela Merkel believed her legacy would be determined by the fate of the eurozone.

Not any more. The refugee crisis will define her years in power.

Angela Merkel believes the migrant crisis is the most important issue facing Europe

She is already framing German hospitality through the prism of history: "I am happy that Germany has become a country that many people outside of Germany now associate with hope."

In the background, however, there is growing criticism.

Germany might have displayed leadership but has been "dangerously naive".

The charge is that it has triggered a global migration that Europe will be unable to control.

Germany misread the power of communication and globalisation.

When Germany said that it would process asylum seekers wherever they had entered the EU, it sent a powerful signal that travel restrictions were easing.

The policy was aimed at the Syrians and Iraqis fleeing the horrors of war, but on the roads and trains across Europe are thousands of people who see this as an opportunity to move to the EU.

Among those fleeing war are groups of Pakistanis, Bangladeshis and Nigerians.

It is hard to calculate what percentage of those arriving are refugees or economic migrants.

The UN believes, external that 50% of those arriving by sea are from Syria.

The figure is much higher on the land-route north from Greece.

Smartphones

And as several leaders have pointed out, Europe has a duty to offer asylum to those fleeing conflict.

Smartphones mean that migrants can keep informed of the latest developments

Another feature of this migration is the use of smartphones. Many of those moving through Europe follow the news closely.

They are well informed and see this as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to come to Europe. Many of them fear the window will close.

The German government has tried to reassure the public by saying it will robustly separate economic migrants from refugees.

It will not be easy. Will Europe really deport Pakistanis back home? Or will Germany just move against those who have arrived from the western Balkans, from Kosovo and Albania?

Some of Europe's politicians - mainly from the right - are in full cry.

The Hungarian leader Viktor Orban believes that Germany has acted in its own economic interest with little regard for the rest of Europe.

In France, Marine Le Pen says: "Germany is probably thinking of its moribund demographics, and it is probably trying to lower salaries again."

Anxiety in Berlin

In truth, Berlin is more anxious about the path it has chosen than it reveals.

Angela Merkel's coalition partners, the CSU, say the easing of the travel rules was a "wrong decision".

Many migrants are relieved to have made it safely to Germany

Its leader, Horst Seehofer, says: "There is no society that can cope with something like this."

So behind the scenes, Germany is exerting huge pressure on other countries to share the burden.

Mrs Merkel persuaded French President Francois Hollande to ditch his doubts.

She nudged the Spanish Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy, into softening his opposition to quotas.

It has been a display of German power and influence.

German warnings to those countries resistant to taking in refugees have a hint of threat about them.

Angela Merkel says, external: "What isn't acceptable in my view is that some people are saying this has nothing to do with them. This won't work in the long run. There will be consequences."

Her Deputy Chancellor, Sigmar Gabriel, has warned that Europe's open borders - enshrined in the Schengen agreement - are at risk.

This would not just be a political blow for Europe but also a "heavy economic blow".

That focuses minds in Eastern Europe, so economically dependent on Germany.

Angela Merkel has admitted that "what we are experiencing now is something that will change our country in the coming years".

Different perspective

But in parts of Eastern Europe, they do not want to change their countries.

The Prime Minister of Slovakia, Robert Fico, describes the idea of quotas as "irrational", external.

Slovakia Prime Minister Robert Fico has expressed concerns over migration quotas

"Migrants do not want to stay in Slovakia," he said.

"There is no base for their religion here."

The Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orban, believes that the identity of Europe will be changed by the large number of Muslims among the refugees.

The President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, warns that this exodus could last for years, external and that "it is important to learn how to live with it without blaming each other".

Certainly Europe will be changed by these past weeks. The faces on the railway tracks will be the faces of new Europeans.

Many will settle and stay. It will require enormous sensitivity and skill on the part of Europe's leaders to pass on Europe's values to new arrivals. It will be a historic challenge.

Germany's generosity might transform the relationship between Europeans and people in the Middle East.

But if the numbers prove impossible to manage, if ordinary Europeans become fearful that the nature of their societies will change, then Mrs Merkel will be blamed for a profound miscalculation with implications for European unity.

Schengen Agreement:

The Schengen Agreement led to the creation of Europe's borderless Schengen Area.

The treaty was signed on 14 June 1985 by five of the 10 member states of the European Economic Community, near the town of Schengen in Luxembourg, but wasn't implemented for a further decade.

It proposed the gradual abolition of border checks at the signatories' common borders.

The Schengen Area operates very much like a single state for international travel purposes.

There are external border controls for travellers entering and exiting the area and common visas, but no internal border controls.

It currently consists of 26 European countries covering a population of more than 400 million people. The UK and Republic of Ireland have opted out.