Migrant crisis: Who does the EU send back?

- Published

Roszke, Hungary: Refugees have crossed from Serbia desperate to reach Germany, but now a razor-wire fence has gone up

For months now Europeans have been witnessing chaotic scenes of migrants pouring into Greece, Italy and Central Europe.

The EU is playing catch-up, struggling to co-ordinate asylum policy between 28 member states.

But it is a sensitive issue, affecting sovereignty and national relations with diaspora communities, such as Afghans in the UK, or Algerians in France.

The UK, Ireland and Denmark opted out of most EU asylum policy, sticking to their own rules.

The focus now is on a mechanism to distribute 160,000 new asylum seekers across the EU - but countries are arguing over that.

Many will qualify as refugees - especially those who fled Syria, Afghanistan or other conflict areas. A refugee is someone fleeing war or persecution, with a right to international protection.

But how many failed asylum seekers are sent back by EU countries? Is there any EU-wide pattern on asylum?

These Syrians made it to Lesbos, Greece - but migrant tragedies at sea have shocked Europe

Identity checks

In 2015 the largest migrant groups in Europe by nationality are Syrians, followed by Afghans, then migrants from Eritrea, Nigeria and Somalia.

War and human rights abuses have plagued all those countries, so many of those asylum seekers count as refugees.

But each case is different - some will find it harder than others to prove their refugee credentials.

Many lack passports or other ID, having risked their lives in the Mediterranean and Balkans, abused and exploited by criminal gangs.

Establishing nationality can be a long process - and those decisions can be disputed by countries asked to take migrants back.

Many migrants reaching the EU from sub-Saharan Africa or the Western Balkans fail to get asylum, as they are classed as economic migrants.

Spain's Melilla enclave in North Africa is a magnet for migrants - despite the fence

One of the incentives for irregular migrants is the fact that fewer than half of failed asylum seekers are actually expelled.

In 2013 the EU sent back just 39% of those refused asylum, the EU Commission says in its European Agenda on Migration, external.

Another stumbling block is that agreements with non-EU countries on asylum returns are quite patchy.

Many readmission agreements have been negotiated, for example with Pakistan and Bangladesh. But the EU has no such deal with China or Algeria.

And the Cotonou Agreement, external, obliging sub-Saharan African countries to take back failed asylum seekers, has not stopped a huge exodus of economic migrants from there. The Commission admits that the EU must offer more aid, to facilitate more migrant returns to Africa.

There are also plans to widen the mandate of Frontex, the EU border agency, so that it can help send migrants back.

But Libya, plagued by fighting and crime, is a problem for the EU because it is a major transit country for migrants.

Nations are bound by the UN principle of "non-refoulement", external - meaning no push-backs to life-threatening places. Greece has been criticised for violating that principle.

German influx

In 2014 Germany was the biggest recipient of new asylum claims, with an estimated 173,100 asylum applications. That put it ahead of the United States, with 121,200, the UN refugee agency UNHCR reports, external. And Germany expects as many as 800,000 non-EU migrants this year.

In third place was Turkey (87,800), then Sweden (75,100). The UK received 31,300 new applications. Currently the top three nationalities for asylum seekers in the UK are Eritrea, Pakistan and Syria, in that order.

A successful asylum claim often means the authorities granting an applicant refugee status - the fullest protection, entitling a migrant to stay, get a job and eventually get citizenship.

But an asylum seeker can also get subsidiary protection status. It means the applicant does not class as a refugee under the 1951 Refugee Convention, external, but still needs international protection. The UK uses the term "humanitarian protection" for that.

What happens to failed asylum seekers?

EU migration: Crisis in graphics

EU data shows huge variation in the handling of asylum claims.

Germany has by far the most claims, but does not send the most migrants back.

UK expels most

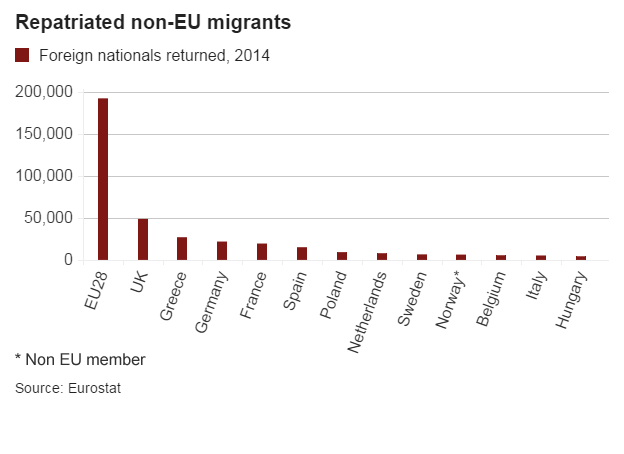

In 2014 the UK topped the list for non-EU migrants sent back - 48,890 out of an EU total of 192,445, Eurostat reports., external However, last year the UK had ordered 65,365 to leave.

Next were: Greece (27,055 returned, out of 73,670 ordered to leave) and Germany (21,895 returned, out of 34,255 ordered to leave). Strikingly, France returned just 19,525, despite having ordered 86,955 to leave.

The total deported from EU countries was less than one-third of the non-EU nationals found to be illegally present, which totalled 625,565.

Susan Fratzke, an expert at the Migration Policy Institute, external, says the UK has cultivated long-standing ties with certain countries, such as Pakistan, making it easier to send back failed asylum seekers.

"It's really these bilateral arrangements that are most effective, rather than EU-level agreements," she told the BBC.

Spain has strong co-operation with Morocco to keep migrants out of Ceuta and Melilla - enclaves sealed off with huge razor-wire fences. Spain refused entry to the most migrants last year - 172,185, or 66% of the EU total, the European Migration Network reports., external

Safe or unsafe?

UK Home Office data, external on migrants removed - voluntarily or by force - reflects the nationalities more or less likely to get asylum in the UK. So 5,684 Pakistanis, for example, were removed, compared with 875 Afghans. The Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan makes many parts of the country unsafe.

The UK also removed 2,184 Nigerians, but just 49 Eritreans. "Removed" does not always mean sent to their country of origin. Often they go to a third country, where they may have settled previously.

Eritreans are one of the biggest groups claiming asylum in the EU, and usually, like the Syrian migrants, they get refugee status. The EU has prioritised those two nationalities for resettlement.

Eritrea is under international sanctions, condemned for human rights abuses, including harsh military service that can last many years.

Turkey hosts more than two million refugees from war-torn Syria and Iraq, including these Yazidi children in Midyat

In 2014 asylum applicants from Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and Somalia had a success rate above 50% in the EU, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) , externalreports.

But the rate for applicants from some other countries wracked by conflict and instability was 20-50%, including Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Mali, Ukraine and Pakistan.

For applicants from the Western Balkans (including Kosovo, Serbia and Albania), Algeria and Georgia the success rate was below 10%.

Germany is among those calling for an EU-wide list of "safe" countries, to make it easier to expel Western Balkan economic migrants. More than 40% of asylum applicants in Germany are from that region.

Many of those asylum seekers are Roma (Gypsies), fleeing dire poverty in Kosovo and elsewhere. But asylum officials still have to decide whether the discrimination suffered by many Roma amounts to persecution.

Wrangling over Dublin

A further complication is the EU Dublin Regulation, external, which is de facto suspended because Germany is no longer sending back Syrians to other EU countries.

Under Dublin, the EU country where an asylum seeker first arrives has a duty to process their claim. But it does not work because Greece, Italy and Hungary cannot cope with the influx.

It is another reason why more migrants are not deported.

According to Ms Fratzke, Dublin is not properly aligned with migration realities. Migrants have preferences about where they want to live - even if those preferences are not grounds for asylum.

And it is easy for migrants to move to another country in Europe's open-border Schengen zone, covering most of the EU. "There are pressures for people to act outside the [Dublin] regulation, if they have no family there, or don't speak the language," she said.