After Alan Kurdi, migrants still risk death in Bodrum

- Published

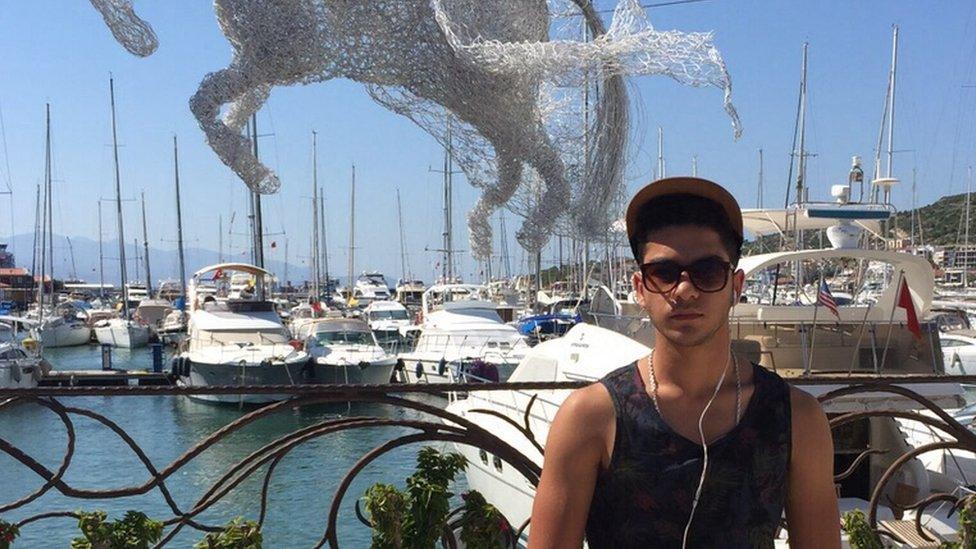

Bakr al-Dalemey has been missing since the boat he was travelling in sank

The BBC's Mark Lowen in Turkey's Bodrum peninsula - where the body of three-year-old Alan Kurdi was washed up last week - meets those desperate enough to risk their lives crossing to Greece.

Omar al-Dalemey peers at the map on his phone, trying to recall from which cove they departed.

"It was pitch-black - the smuggler just told us where to meet," he says. Finally he remembers, pointing to a spot on the Bodrum coastline. "It was there".

We arrive, and he and his parents walk towards the rocks.

"The boat could hold 10 people," he says, "but we were 17. We had lifejackets. The man said he'd hand them to us when we got into the boat. But as we boarded, he threw them away. If we died, he didn't want any trace of us."

Omar and his brother Bakr were among the passengers. Sunni Muslims from Iraq, they were fleeing persecution in Baghdad.

More than half of the refugees to Europe are Syrian - but there are plenty of other nationalities too.

And as the European Commission outlines plans for a quota of migrants for EU countries, we met some of those from other nations beginning their journey in Bodrum.

"The waves grew higher, water came into the boat and we capsized," says Omar, staring out to sea.

"We swam for a long time and suddenly I couldn't see my brother anymore. When the coastguard arrived, all I could think about was Bakr's safety."

Desperation forces migrants to use barely seaworthy boats

'I wish I was the one dead'

For a week, there has been no sign of 17-year-old Bakr. His family have combed the coastline - even visiting the mortuary.

Did he make it to Greece? Was he arrested? Or something worse? Their father breaks down beside us, covering his face to hide the tears.

"I wish I was the one dead - and that he's still alive," says Omar.

Their mother, Nawal, is locked in the unbearable state of not knowing. And, amid the vastness of the Aegean Sea, she may never find out.

"Bakr was the sweetest of us all," she says, sobbing. "Smart and handsome. Can you imagine losing the most precious thing you have?"

She looks out to the area where the boat capsized. "I will stay here until I find him," she says.

An exhausted Syrian man lies on a Greek beach after being pulled from the water

People smugglers thrive

The number of nightly departures from Bodrum appears to have slightly decreased after police stepped up patrols here in the wake of the Alan Kurdi tragedy.

The body of the three-year-old boy was washed up in Bodrum - the photograph of the little boy lying dead on the beach shocked the world. But beside the central bus station, crowds still gather, waiting for the chance to flee.

The nationalities come together here seeking shelter: Afghans in one corner, Somalis in another. Perched on bits of cardboard are a Pakistani couple who sold their home to pay the smuggler.

He has now disappeared with their money. The woman, Shabana Waqaz, is due to give birth in a week.

"It took us a month to reach here and now our agent has run away with our $2,000 (£1,300, €1,794)," she says. "We're stuck here - we can't go on and we can't go back. I have no medical care for the baby; I don't know how I will deliver.

"All we wanted was the chance of a better future for our children."

Overloaded boats attempt the crossing to Greece daily

As the sun sets on the Bodrum peninsula, the old castle is silhouetted, the holidaymakers pack up for the day - and the smugglers ply their trade.

They have willing customers from every stricken nation here. Some will never make it, caught in a no-man's-land of the refugee crisis or engulfed by the rough waters.

But they will still try. Because, from the shores of Bodrum, the dreams of Europe burn bright.