Turkey-PKK conflict: Children caught in the crossfire

- Published

Children are often the principal victims of a conflict that has lasted for three decades and killed 40,000 people

Emine Cagirga has kept three bullet casings she found from the day her daughter was shot. The fourth was lodged in Cemile, 10, who died instantly.

Numb with grief, Emine sits in her garden, a photograph of her daughter pinned to her dress.

Cizre has seen some of the worst violence since a two-year-long ceasefire between the Turkish state and the Kurdish rebel group, the PKK, collapsed in July.

With the town under curfew for nine days, no ambulance came for Cemile. And her family could not leave their house to bury her.

"It was sniper fire," says Emine. "Cemile was at the front gate. I ran towards her, shouting her name. She collapsed. 'Mama,' she said. And then she died."

The death of Ermine's 10-year-old daughter Cemile left her numb with grief

"I kept her body beside me until the morning and held her hand," Emine recalls, staring into the distance.

"Then I took her to the fridge and put her inside. I didn't want her to decay. We kept her there for two days until we could bury her."

Emine has now moved the fridge next door since her other children were so terrified of it. She takes me to see it: a grim memory of her family's darkest hour.

"Cemile was an angel - she was part of my soul," Emine says. "How can the government bring this pain upon mothers? In God's name, what do you want from us?"

The BBC was given rare access to the militia - comprised mostly of disenchanted teenagers - that is manning barricades in Cizre

Across Cizre, the marks of war are clear

'Colluding with IS'

The violence in south-east Turkey was sparked by a suicide bomb, which exploded in a Kurdish-majority town and was blamed on Islamic State (IS) militants.

Kurds, however, accused the Turkish government of colluding with IS, and the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party) shot dead two Turkish policemen in response.

Turkey resumed airstrikes on PKK positions in Turkey and Iraq - and the tit-for-tat violence was unleashed.

More than 120 Turkish security personnel have since been killed by PKK bombs and the government says hundreds of militants have died.

Mark Lowen inspects the recent scars of battle in the Turkish town of Cizre

The armed conflict between the two sides that lasted for three decades and killed 40,000 people now looms once again.

Across Cizre, the marks of war are clear.

Buildings are riddled with bullet holes and scarred by shrapnel. Makeshift barricades of rocks and sandbags are still in place. Armoured police vehicles dot the town, poised to move in.

The government says the operation there was to flush out the PKK from its hotbed, claiming only one of those killed was a civilian, the others militants. Locals say more than 20 civilians died.

We had rare access to the militia manning the barricades with weapons. They make up the YDG-H, often referred to as the youth wing of the PKK.

'Erdogan's war'

We found members on the streets of Cizre: disenchanted teenagers who don hoods and assemble small arms, they say in self-defence.

This week three policemen were killed by a roadside bomb in Mardin

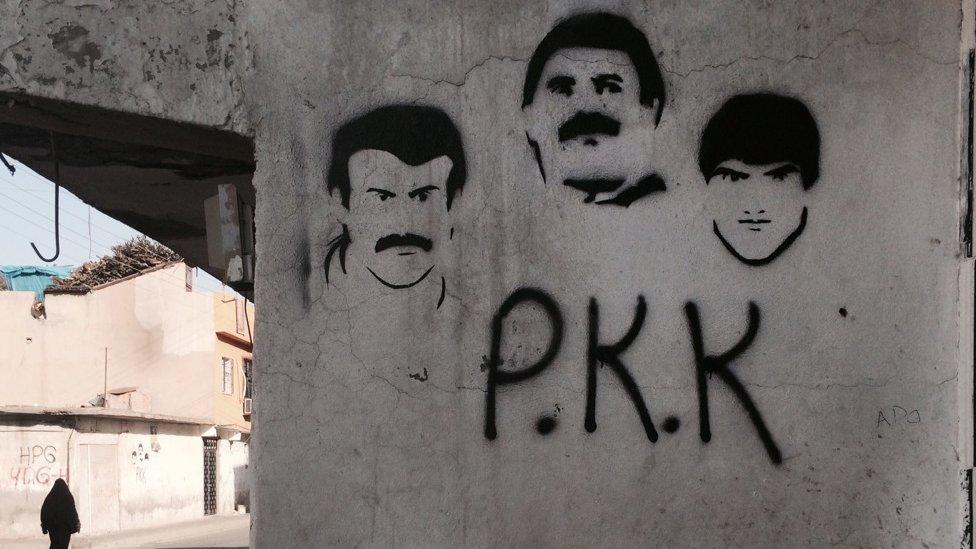

Support for the PKK in Kurdish-majority Cizre is clear to see

Two boys - both 18 - take us into a house to talk more. Inside, they reveal crates of Molotov cocktails - beer bottles with petrol and a fuse made of fabric - and a couple of rifles they keep.

As night falls, they stand outside, blocking access to their street, petrol bombs and rifles at the ready. "A last resort," they say. They co-ordinate with other teams by walkie-talkie.

"The police have killed children and our mothers and fathers," says one. "We don't want to use guns. I'm a student, I want to use my pen. But how can you defend yourselves against an enemy with a pen? This is their war - it's [President Recep Tayyip] Erdogan's war."

He tells me he has received weapons training.

So would he eventually join the PKK, I ask.

"If my other friends are killed of course I'll join it, and avenge their deaths."

Suddenly they get word of a possible police operation overnight. Fearing an incursion, locals have blocked side roads with vehicles. A group comes out to push aside a truck so we can exit. This is a turf war that is escalating fast.

'Crime against humanity'

The government has vowed to push on with operations in Cizre and elsewhere to regain control and crush the PKK, classified as a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the EU and US.

Funerals have recently been held in Cizre of those people killed in recent clashes with the security forces

This week, again, three policemen were killed by a roadside bomb in the nearby city of Mardin. At their commemoration, the coffins are draped in Turkish flags. They are labelled "martyrs".

The brother of one stumbles towards the coffin, sobbing. Suddenly the tears stop and he faints, overwhelmed by grief.

"The PKK must stop this terrorism, which is a crime against humanity," says Omer Faruk Kocak, the governor of Mardin.

"Turkey is acting against terrorist organisations as every country would. They have infiltrated civilians and are using them as human shields."

Mardin Governor Omer Faruk Kocak has accused the PKK of committing crimes against humanity

Critics say President Erdogan resumed the conflict with the PKK in order to win back nationalist votes after inconclusive elections in June and before another snap poll in November.

His strategy is to crush the pro-Kurdish HDP party that deprived the government of a majority. In the current frenzy, nationalist mobs have attacked HDP buildings across the country, spurred by pro-government media that scream the word "terrorists".

But Mr Kocak says it is not a political game.

"This is a stupid assertion," he says. "Turkey has never played politics with human lives."

At the cemetery in Cizre, the graves of last week's victims lie beside those from the armed conflict of the past.

Turkey is spiralling further into chaos. And unless both sides pull back fast, the consequences could be devastating.

- Published15 September 2015

- Published23 August 2016

- Published25 July 2015

- Published15 June 2015

- Published24 March

- Published22 August 2023