Catalan election: Looming independence or little change in Spain?

- Published

- comments

Plaza Colon: a symbol of Spanish unity or an affront to its regions, depending on your politics

Nationalist-minded Spaniards adore Plaza Colon in central Madrid, though others might be tempted to describe it as indecently huge or even wildly unsubtle.

A massive Spanish flag dominates the otherwise bare, concrete square and the countless lanes of gridlocked traffic around it. A booming red-and-yellow message of national might, emanating from the capital city.

When I first moved to Madrid, a Basque friend of mine took me to Plaza Colon as a key point of interest.

"Look at that insult," he said. "A huge two fingers up by the Madrid government to us in the rest of Spain. What about regional sensitivities?"

The Madrid-centrism of Franco's military dictatorship, when regional languages and culture were banned and their prominent human defenders imprisoned or murdered, still divides Spain, 40 years after his death.

Just how polarised society can be was clear from the headlines in the bestselling Spanish papers following Catalonia's regional elections.

Front-page news in the centre-left El Pais and centre-right El Mundo described a "disaster" for the pro-independence camp, which "failed to get a majority of votes".

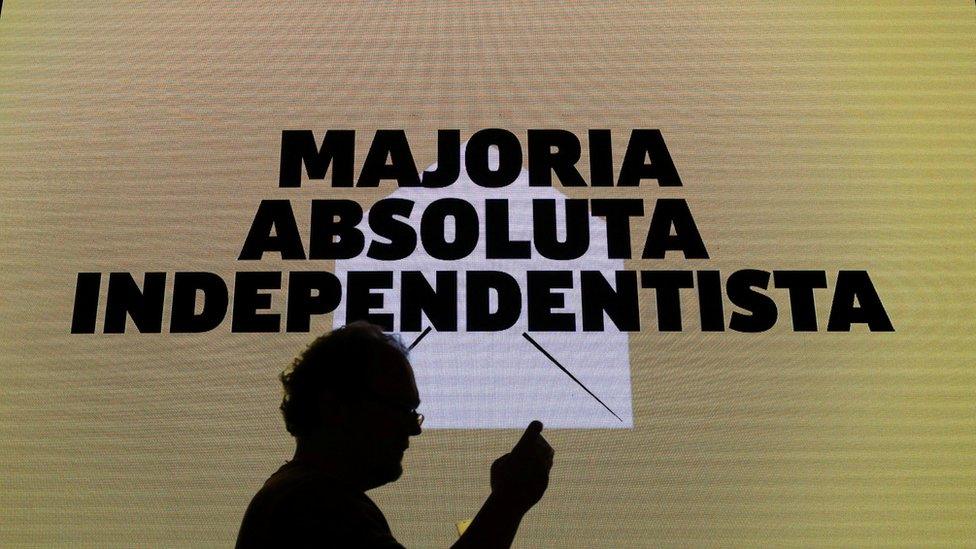

The national broadsheet, La Vanguardia - published in Catalonia - screamed: "Absolute majority for the independence parties with record voter turnout."

Support for Catalan independence has been fuelled by Madrid's perceived neglect of the region

Confused? Of course. And every Spaniard will interpret the complex results of the Catalan elections according to his or her personal convictions.

Independence debate gets personal

Catalonia's quarrel with Madrid

Independence campaigner Thais Botinas told me today the vote was a clear victory for independence, though she wished it had been even more decisive.

Antonio Lopez-Isturiz, a member of the executive committee of the Spanish People's Party in national government, could not have been more dismissive.

"We see the situation no differently today than yesterday or the day before," he told me. "This was just a regional election, not a fake referendum or anything else. Nothing whatsoever has changed."

Except it has, of course. On the back of yesterday's election, the pro-independence grouping can claim an absolute majority, with the backing of the radical left CUP - an awkward bedfellow, if ever there was one.

Catalan regional President Artur Mas says he will start taking steps towards declaring independence within 18 months.

Radio shows and social media in Catalonia are alive with excited rumours that Madrid might send tanks rolling into Barcelona.

Catalan leader Artur Mas believes the election paves the way for independence

It is far more likely that Madrid will send in the lawyers. Breaking away from the Spanish Mothership goes against the country's constitution.

Certainly nothing will happen overnight.

Spain's governing Popular Party is far more concerned about the upcoming general election. Whoever wins is likely to negotiate more fiscal autonomy - at the very least - for Catalonia.

Mariano Rajoy's Popular Party leads opinion polls but the outcome of national polls later this year is unclear

The region's grievances with the rest of Spain have as much to do with economics as politics. It contributes roughly one-fifth of Spanish national GDP in taxes but feels it gets far less back.

Certainly state investment in Catalonia has gone down in recent years.

Like the rest of Spain, Catalonia suffered hugely as a result of the euro crisis. Unemployment is still high in the region, and education and state healthcare are worsening.

But Catalans feel their hard-earned tax money is now being directed by Madrid to prop up worse-off Spanish regions.

People power

Rather than sending a decisive message about regional independence, Catalonia's regional election is a clear signal of something else we are witnessing across Europe.

That is, the re-engagement of people in politics - through movements that are fighting the powers that be: a popular revolt against the status quo for, in theory, more transparency and people-oriented politics - both left- and right-wing.

Many protesters in Spain - as in Greece and other parts of Europe - have taken aim at what they regard as an unaccountable elite

These are the sentiments driving the rise in popularity for Labour party leader Jeremy Corbyn and UKIP in the UK, for Marine Le Pen's National Front in France, the Five Star Movement in Italy, and Syriza in Greece.

Catalan independence is a popular movement. There were screens up even in tiny village squares across Catalonia on Sunday night as people breathlessly waited for votes to be counted. And the 77% voter turnout broke records for a regional election.

Those arguing for Catalan independence resent Madrid governing their lives, making decisions for them in what they see as a corrupt, high-handed and mistaken manner.

It is also interesting to note that the second-largest political group to emerge out of the Catalan elections was the anti-independence Citizens (Ciudadanos) party.

It is currently taking all of Spain by storm as a fresh centre-right movement promising greater transparency and an end to corruption, as well as citizen-consultations to keep its politics people-focused.

One crisis among many

On a European level, the Catalan elections have made ripples rather than waves. There were no big screens up in the EU institutions' buildings for the Catalan vote.

The European Commission insists this is a domestic issue for Spain.

Catalonia's separatist ambitions are likely to re-emerge on the EU's agenda

Unlike 15 years ago, following the break-up of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, when Basque separatism, Corsican independence, and Northern Italy breaking away from the rest of the country were the talk of Brussels, there is now less of a focus on regional independence movements, although Scotland often features during dinner-table debate.

Antonio Lopez-Isturiz, who is also Secretary General of the European People's Party, said that with crises in migration, the eurozone and Greece, Catalonia did not even figure.

But it will almost certainly re-emerge when Spaniards go to the polls before the end of the year.

- Published28 September 2015

- Published18 October 2019

- Published25 September 2015