Syria crisis: How far do Russians support intervention?

- Published

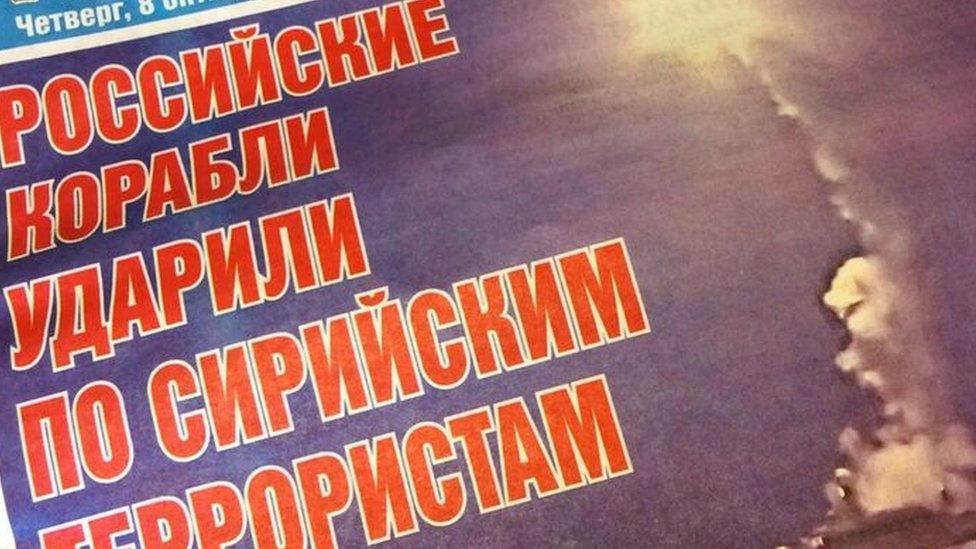

Russia's actions follow weeks of military build-up in Syria

With fighter jets flying up to 70 sorties a day in Syria, Russia's powerful media machine has gone into overdrive.

News and discussion programmes on state-controlled television are dominated by talk of the conflict and deliver a common message: that western policy in Syria has failed and President Vladimir Putin has stepped in to the rescue.

"Russia is saving Europe from barbarism for the fourth time," the notorious anchorman Dmitry Kiselyov crowed on his weekly show.

"Let's count: the Mongols, Napoleon, Hitler - and now Islamic State."

The criticism from abroad, that Russia is actually ignoring IS targets to focus on opposition to President Bashar al-Assad, is dismissed as propaganda.

"This is truly a matter of national security," foreign ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova told a packed press room this week.

"We've experienced terrorism. We don't want to go through that again."

As the vast majority of Russians get their news from TV, the message is starting to penetrate.

A poll this week by the independent Levada centre in Moscow revealed that 72% of Russians support the airstrikes.

That is a dramatic turn-around since the last survey before the military and media campaigns began, when a majority were opposed.

It is a reassuring result for Vladimir Putin, for whom the Syria campaign is another chance to play the strong man and reassert Russia on the global power map.

The first cruise missiles modern Russia has ever launched in combat were fired on his 63rd birthday; the dramatic images were screened repeatedly, almost like celebratory fireworks.

The next day's newspapers hailed the barrage as proof that Russia is back to rival the USA, after President Putin's massive investment in a military modernization drive.

A Russian media offensive has accompanied operations in Syria

But the Levada centre survey revealed another important statistic.

"There is a clear fear that Russia will get stuck in Syria, like the Soviet Union did in Afghanistan; that this will be a long campaign, with human sacrifice and great cost," the centre's director Lev Gudkov points out.

That is despite repeat assurances that Russia will not deploy ground troops.

"The Kremlin is underlining that this is a short-term operation, and only from the air. But what happens if militants attack the Russian airbase? It's completely unclear how things would develop then," Mr Gudkov adds.

And there is another problem brewing.

Russia is busily portraying its Syria campaign as a war on terror. But the fact that it is supporting a Shia-led alliance against Sunni opposition has not been lost on its own Muslim population.

At least 11% of Russian citizens are Muslim, most of them Sunni.

Russian Muslims have privately expressed unease over the campaign

At a recent ceremony at the new Moscow central mosque many expressed support for the policy of Vladimir Putin.

They echoed a speaker inside who blamed the United States for sowing chaos in the Middle East.

"They want to divide the Muslim world," Adam Delimkhanov argued.

But privately, other mosque-goers voiced concern.

"That's just politics," one man commented of the speech. "Of course we're worried. They're bombing Sunnis."

Even official figures here show that more than 2,000 former Soviet citizens have joined the ranks of I.S and other extremist groups in Syria.

Russian air strikes - in depth

Russian jets have been carrying out operations over Syria

Where key countries stand - Who is backing whom

Why? What? How? - Five things you need to know about Russia's involvement

What can Russia's air force do? - The US-led coalition has failed to destroy IS. Can Russia do any better?

Inside an air strike - Activist describes "frightening Russian air strike"

Syria's civil war explained - Analysis and background on the conflict

Reducing their threat to Russia was the official reason for starting airstrikes. But there is a danger the policy could radicalise people instead.

"There will definitely be consequences here in Russia, some response from IS," one young Chechen called Mansur said.

"They won't just leave it at that," he added, admitting that he was worried about a possible terror attack.

Some commentators suggest President Putin hoped his actions in Syria would help thaw relations with the West, even soften the painful sanctions imposed over his last intervention, in Ukraine.

But the signs so far have not been promising. Instead the Syria campaign risks adding new pressure to Russia's already weakened economy.

The short-term impact will be minimal as the vast defence budget is pre-allocated. But Russia is now firing its latest cruise missiles and if the conflict drags on, the costs will mount.

There are fears Russia could be dragged into a long-term engagement

"We have to pay for this military action. A big figure, and in this complex economic situation," politician Dmitry Gudkov points out.

The only independent deputy in Russia's parliament, he says MPs never discussed the intervention.

But he argues that behind the headline 72% public support, commitment to this campaign does not run deep.

"Maybe the government decided to shift attention from Ukraine to Syria," Mr Gudkov suggests.

"But it's too far from our country. Russian TV needs to work hard, to make people focus on this agenda. I know state media are broadcasting the situation non-stop, but I think Russians are not really interested," he explains.

For now, Vladimir Putin's decisiveness and posturing before the West are winning him plaudits.

But he has no obvious exit strategy from this conflict and the longer it goes on, the greater the risks to both Russia and its President.