'Missing' Syrian boy Azam now found

- Published

The BBC's John Sweeney has found Azam - a young boy who vanished from a hospital in Belgrade a month ago while on the refugee trail. The story sparked a social media campaign using the hashtag #FindAzam. After a week on the road - travelling from from the bottom of Serbia to the top of Germany - Sweeney found Azam and his uncle.

You can watch the full film for BBC Newsnight here., external

Read more about how John Sweeney found Azam, and how he is doing now, here.

Sunday 25 October: The madness of hope

Dawn mist cloaks the hillside, shrouding the apple orchards and cornfields of northern Serbia into a ghost-world. The cold creaks in your bones.

Mist hangs over the early morning near the border with Croatia

Up a little lane a family from Damascus are warming their hands around a fire, heating a small pot of water to make coffee. The father holds a baby-carrier by its cloth straps over the flames to take off the chill. I give the family our poster about Azam and the father reads out the Arabic, apologises that he cannot help but keeps the poster and promises to tell his friends when he gets to Germany.

The BBC's John Sweeney gives a tour of a refugee crossing point on the Serbia-Croatia border

The consideration for Azam from people who have nothing but a dream of a life better than barrel bombs and severed heads is extraordinarily moving. But alongside grace under pressure, there's plenty of ignobility too.

Over the crest of the hill is the tiny border crossing at Berkasovo, where Serbia stops and Croatia begins. The Serb authorities recorded 10,000 people entering the southern end of the country in one day three days before. On this morning, something like that number are pressed into a human cattle pen, queuing to get into Croatia, which allows only pockets of 50 to cross at one time. When 10,000 people have to wait for a whole day to move 300 yards, you get Bad Glastonbury: acres of gelatinous mud, stinking rubbish, ugly squabbles, queue-jumping.

A small fire and a pot of water to make coffee are all one family have to stave off the cold

Bossing the wretched of the earth are two lots of burly policemen in subtly different uniforms, Serbs and Croats, cracking jokes with their mates, turning grim for the refugees. But 24 years ago I saw Serbs and Croats close to here in Osijek and Vukovar kill each other - and a friend of mine, photographer Paul Jenks - for no good reason. The people in the queue from hell want to get away from killing. There is a difference.

The best place for 20 million Syrians to live is Syria but there is a pitiless war going on there now which no-one, it seems, has the power to stop. On Sunday the European countries most affected by the wave of refugees (and the economic migrants coming along for the ride) are meeting in Brussels to address the consequences - but not the causes - of that war. In the meantime, thousands queue in misery and mud.

Inside the human cattle pen, the crowds and the mud are reminiscent of Glastonbury; but the mood is solemn

One Serb copper went out of his way to sneak families with shivering kids to the top of the queue. His colleagues noticed and he stopped his crime towards humanity. If you're very, very sick or have a screaming kid, you can jump the queue. A young man with cerebral palsy was lifted in his wheelchair by his family over the sea of rubbish, the whites of his eyes fluttering in their sockets. A young Palestinian couple shuffled through the mud; her face was blue with cold and she was heavily pregnant. I tried to help this contemporary Mary and Joseph but failed. Pregnant women are commonplace.

Watching the people suffer so much on the long road north, you can't help but feel this is a kind of madness, a collective psychosis. Simon Wessely, the president of the Royal College of Psychiatry, told me: "I don't think we would call it a collective psychosis. It might be a perfectly rational way of behaving in utterly irrational circumstances. I am not entirely sure I would not do the same if the circumstances were reversed. Of course, Germany or wherever will not be the earthly paradise they might be expecting, but given that many of them are living in a man-made hell one can again sympathise. And also we need to dream a little - El Dorado, Prester John, the Soviet Union in the 1920s, at least gave hope and optimism even if illusory. They may be fearful, terrified, irrational, but psychotic they are not."

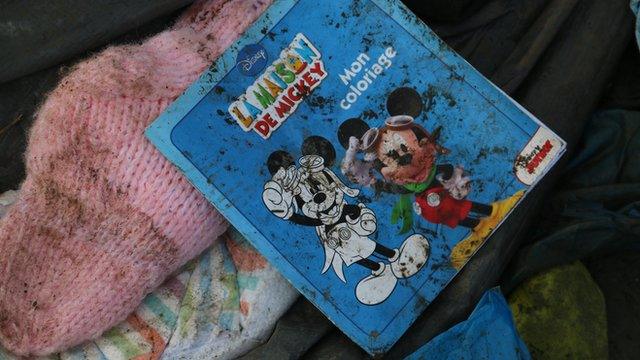

Debris which lies muddied offers a glimpse into the lives of people on the road north, among them many children

I taped a poster of Azam to a tree and we headed north. The Belgrade police suspect Azam and the man with him, Geyeer Aldaham - we think that's his name - travelled from Belgrade to Budapest. (Now Hungary has closed its border, the main track has shifted 100 miles to the west, via Croatia and Slovenia.)

When Azam passed through their country, the Hungarians bar-coded refugees and migrants. Did the Hungarian bar-code system track Azam? We asked the Hungarian authorities and they said they had no record of a boy called Azam Aldaham. The Belgrade police have had a tip-off that Azam ended up in Munich in mid-September - and that's where we are going right now. The search for Azam continues.

Saturday 24 October: We're retracing the steps we think Azam and the man with him might have taken.

That's brought us to Berkasovo - the main refugee crossing point on the Serbia-Croatia border.

Nightfall at the crossing. It's dark, but for the moon in the sky

A disabled man is carried towards the border

There's a big bottleneck - thousands of people are backed up, but only 50 are allowed to cross the border at a time

This man is Palestinian and has come from a refugee camp in Damascus

About a quarter of the people now crossing through Serbia are children

This little boy - like many of the people we've met - is from Syria

Friday 23 October: I have fresh information about Azam and what happened after I last saw him.

I last saw the little boy get into an ambulance in Belgrade in early September with a man who told us he was his father, but we suspect was his uncle. Azam had a black eye and a swollen jaw, possibly broken, which certainly looked infected. The little boy had been howling in pain, crying "I want my mummy", as a Serbian medic cleaned his wounds with an antiseptic wipe. The man with him told us that Azam had been injured in a car accident in Macedonia and his mother had been left behind in Turkey.

On Friday, for the first time, we have a pretty accurate picture of what happened after Azam got into the ambulance. He'd been sent to hospital by Dr Radmila Kosic, a Belgrade paediatrician who was running a makeshift medical clinic where the refugees and economic migrants were camping in a park by the bus station.

First he went to the children's hospital, then a maxilo-facial clinic where he was X-rayed - and the X-ray showed his jaw was broken. At that moment we were still filming in the park and Dr Kosic, informed by her team over the phone, told us that she expected him to stay in hospital for some days.

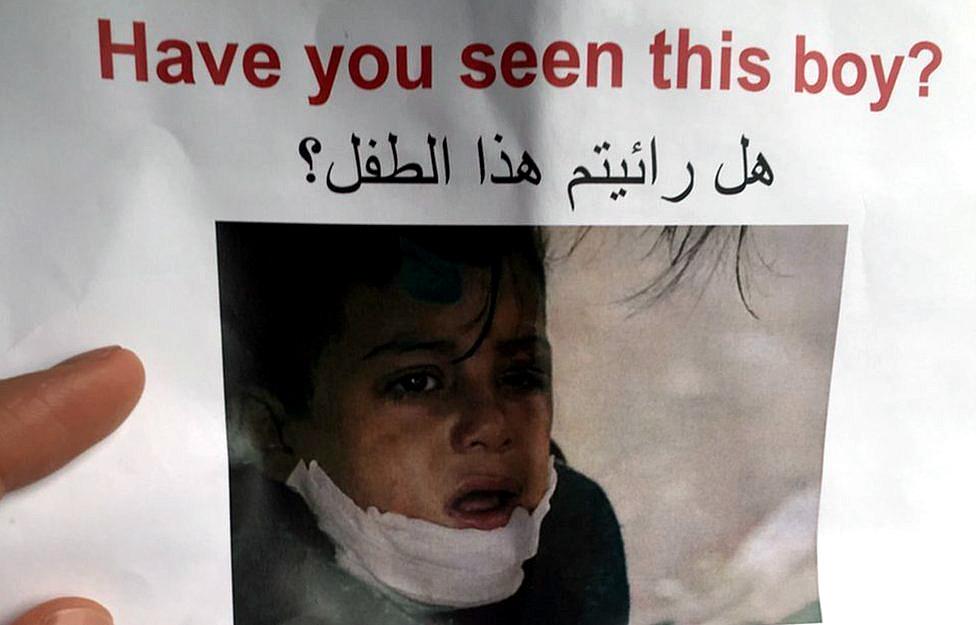

A social media campaign has been launched with the hashtag #FindAzam

Happy that Azam was being treated, we left Belgrade and headed north towards the border with Hungary. But what neither Dr Kosic nor we knew was what happened next. Azam was sent with the man to Belgrade's main accident and emergency centre to see a neuro-surgeon and to have a CT scan to check for brain injuries. Azam and the man saw the neurosurgeon - and then they vanished before the CT scan.

It was two weeks before we were informed that Azam had disappeared that day - and by that time Azam and the man had gone north.

So it's possible that Azam has a brain injury. No-one knows. Dr Kosic is adamant: "The father or uncle was told that he should bring Azam back to the maxilo-facial clinic for treatment. It was wrong for him not to do that."

The head of Serbia's border police, Mitar Djuraskovic, told me: "A hospital is not a jail. You cannot hold someone without evidence, judges, lawyers. In this case, by the time we knew what had happened it was too late."

Serbian police believe that Azam was travelling with a large party of Syrians and that he entered Hungary next - the logical path for refugees at that time.

One extra piece of news. We've found out that the name of the man with Azam - whether he was his father or uncle we still don't know - is Geyeer Aldaham.

The impossible task got that bit easier. Next, we're heading north to rejoin the main the refugee track into Croatia, hoping to find someone who might recognise Azam and know his mother.

Conditions are grim, there is no electricity, no shelter, and thousands of refugees are camping out in the cold while the Croatian authorities are letting only a trickle of people through. One aid worker told us: "It's a humanitarian catastrophe."

We'll be reporting live on the story on this blog (you can bookmark the link) and also on BBC Newsnight's social media accounts - on Snapchat (bbcnewsnight), Twitter, Facebook and Periscope. John Sweeney's report is due to air on BBC Newsnight next week.

Thursday, 22 October: Back at the Serb reception centre where I first met Azam with the man who claimed to be his father.

The rain, the cold, the herding of immense numbers of people, the babies wailing gets to you, makes you want to weep and then the task of trying to find one small boy in this pipeline of humanity flowing from Syria to northern Europe seems not just impossible, but also absurd and foolish.

One month ago I met a small boy, Azam, with a bandaged jaw in Preshevo in southern Serbia, just to the east of the Kosovar mountains. Azam was travelling with 13 men, one of whom claimed to us that he was his father. Azam's mother had been left behind in Turkey, he said.

The very next day I met Azam again in Belgrade. He was howling in pain and alone at a makeshift medical centre. His "father" reappeared and together they went to hospital in an ambulance where Azam was X-rayed. And then he and the "father" vanished.

Ten thousand refugees came through the Preshevo reception centre in one day this week

I'm trying to find Azam and reconnect him with his mother. I don't where she is or even her name but she might be on the road, looking for her son.

In September when we were at Preshevo roughly 3,000 people were coming through the reception centre - a fancy phrase for chaos in small motion - a day.

Two days ago 10,000 people came through Preshevo in one day. And the bad news, according to Seda Kuzucu of the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), is that the majority are families with children.

"The make-up of people crossing has changed. For a while it was 50:50 young men. Now it's 60% Syrian families with young children. Conditions are desperate, the children are suffering from the cold and the rain."

John Sweeney with Dr Radmila Kosic who sent Azam to hospital

So while searching for a lost boy, I'm surrounded by children who have lost their homes, their possessions and even their country.

The Serbian authorities work hard to process people - the majority of whom are refugees from Syria, with a large minority of economic migrants from elsewhere - as quickly as possible so that they can go forward to the next country on the long road north.

But the queue into the reception centre is long and mostly out in the open so people shiver in the driving rain, noses turn blue, babies cry. I'm afraid I can't convey how grim it is in words.

We've printed colour posters in English and Arabic showing Azam and the man who took him out of hospital but to begin with I couldn't bear to ask these poor, shivering, wretches to help us find one small boy.

Eventually, I screwed my courage to the sticking place and started handing out the #FindAzam posters. One young man, an engineering student, originally from Damascus, who spoke good English, read out the poster in Arabic to the people standing next to him, every single one of them soaked to the skin.

An old man, a Syrian Kurd from Qamishli, on the front-line with the so-called Islamic State (Isis), studied the photograph of Azam, and slowly shook his head apologetically. None of them recognised Azam but they got it, they saw the point of what we were trying to do, they gave the problem some attention, and then the queue shuffled on.

These children are not lost, but they’ve lost their homes and their lives

Inside the reception centre proper in a large white tent a Syrian woman, her face numb with cold, studied the poster intently. She, too, didn't recognise the boy and apologised to me. "Where are you trying to get to?" 'Sweden,' she said. I told her to keep the poster and when she gets to Sweden to tell her friends to look out for Azam: 'I will,' she said.

That's what got to me. In the middle of this dreadful inhumanity, on the run from a war between one side that uses chemical weapons and another that chops off heads in high definition broadcast quality, a refugee pays attention to the suffering of one small boy.

My old friend Allan Little, formerly a BBC reporter, used to say of the wars of former Yugoslavia: "in the worst of times, you see the best of people." I can't think a better way of summing up Preshevo in the rain.

So, thanks to people like the engineer, the old man from Qamishli and the woman bound for Sweden, our search for Azam, impossible, absurd and foolish as it may feel, continues.

Next stop, the Belgrade hospital where Azam was last seen.

We'll be reporting live on the story on this blog (you can bookmark the link) and also on BBC Newsnight's social media accounts - on Snapchat (bbcnewsnight), Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Periscope. John Sweeney's report is due to air on BBC Newsnight next week.

Five-year-old Azam was visibly in pain when he was treated by a medic in September

Wednesday 21 October: Look at the pain in this boy's eyes. His name is Azam, he's five years old. His mother is still in Turkey and the man who says he is his father took him from hospital before he could be treated for a broken jaw.

This is a story about trying to find one small boy who's gone missing in the chaos of hundreds of thousands running from a pitiless war in Syria that's killed a quarter of a million people.

I last saw Azam in early September getting into an ambulance in Belgrade with a man who told us he was his father. He was going to hospital to get his jaw treated: it was swollen, bandaged and, we learnt an hour later after an X-ray, broken.

That Azam was being treated in hospital made me feel, OK, let's get on with covering the rest of the long road from the Greek island of Kos to the Austrian border.

But Azam wasn't treated. That very day after the X-ray had been taken Azam and the man vanished - a fact I didn't discover for two weeks.

So for Newsnight I'm going to spend the next week trying to find Azam in Serbia, Hungary and Germany and anywhere else in northern Europe where he may have ended up. I want you to help me.

The report we aired on Panorama at the end of September sparked a social media campaign to try to find him, using the hashtag #findazam. Since then, it's been used more than 30,000 times on Twitter and widely shared elsewhere. Facebook, external and Twitter, external accounts have also been set up.

We'll be reporting live on the story on this blog (you can bookmark the link) and also on BBC Newsnight's social media accounts - on Snapchat (bbcnewsnight), Twitter, external , Facebook, external and Periscope. Please follow along on the journey, and help if you can.

We may never find Azam but at least we're going to try. I want to discover more about Europe's lost children, how many children get split up from their families, how much is being done to reconnect them and how, perhaps, more could be done.

The climax of the late Denis Healey's military career was being a beachmaster at Anzio. But as a lowly officer in 1940, I recall, he was once asked to count all the trains entering and leaving Reading station. The task was so pointless he made up the numbers and he was sceptical about the value and accuracy of statistics ever since. Me, too.

No-one knows for sure how many children have gone missing on the road from the Greek islands to northern Europe this year because no-one can be sure. The situation on the ground is chaotic.

But after I spent two weeks in September making the journey with the refugees and economic migrants, I came away thinking that within the chaos there was more communication than I'd expected.

Using digital

Syria, before the war, was not a rich country but it was never dirt poor. Many people have smartphones, just like us. They use Facebook and Twitter and Snapchat, just like us.

I met one man who, fed up with the charges and prevarications of the Turkish people smugglers, swam the whole way from Bodrum to Kos. He wrapped his smartphone in plastic and used Google Maps to work out how much more he had to swim. And the $1,200 he saved by swimming? He was going to spend it on drinking, just like some of us would do.

That digital connectivity may help us find Azam. But I have no illusions about how difficult it will be. In my time as a reporter, I've tracked down people who were hard to find. In Communist Czechoslovakia in 1988, I went undercover to look for a mother, a Sudeten German, whose son had been murdered in prison.

In 1999 I scoured the length and breadth of Albania, searching for "the man with the burnt hands" whose friends and families had been machine-gunned by a Serbian militia in a hay barn. He had hidden under the dead, one hundred or so.

The militiamen had set the barn on fire and his hands had burnt until he ran for it. He survived and later gave evidence at The Hague against the killers.

In 2008 I found a Chinese athlete who'd been run over by a tank in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Legless, he was refused permission to take part in the Paralympics and his interview gave some discomfort to our official Chinese minder.

But these people weren't so hard to find because they wanted to be found, to tell their stories.

This man was seen carrying Azam in Belgrade. He later took the little boy away with him

And the man with Azam, does he want to be found? It's hard to say. We first encountered Azam on 9 September in southern Serbia at Preshevo. The man carrying him introduced two men, saying that one was his father and the other his uncle.

The next day we met Azam again, at a makeshift medical clinic, in a park by Belgrade bus station. He was alone, screaming in pain as a medic cleaned his jaw with an antiseptic wipe and crying for his mummy.

The doctor treating him, Dr Radmila Kosic, told us that his father had been here a few minutes before. Our interpreter was worried and found out from Azam that the man was his uncle, not his father.

The man returned and said he was the father and had papers to prove it. We were in no position to prove him wrong.

But the doctor said Azam was going to hospital and we watched as the man picked up the little boy and together they got into an ambulance.

That seemed the very best place for Azam. Now we know the man took him away, that very day. I don't know where this story ends. But there is nothing to be lost from trying to shine some light on what happened next to Azam and to find out more about Europe's lost children.

We'll be reporting live on the story on this blog (you can bookmark the link) and also on BBC Newsnight's social media accounts - on Snapchat (bbcnewsnight), Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Periscope. John Sweeney's report is due to air on BBC Newsnight next week.

- Published9 October 2015