Migrant crisis: Czechs accused of human rights abuses

- Published

The UN has condemned "xenophobic public discourse" in the Czech Republic

The UN has accused Czech authorities of "systematic" rights violations in their treatment of refugees and migrants.

The Czech Republic was holding migrants in "degrading" conditions for up to 90 days, the UN's human rights chief said.

Zeid Raad Al Hussein said migrants had been strip-searched to find money to pay for their detention.

But Czech Interior Minister Milan Chovanec said the government "fundamentally disagreed" with the accusations.

He said Mr Hussein was welcome to visit any Czech detention facility in person.

In other developments in the migrant crisis:

Sweden has said that up to 190,000 asylum seekers will arrive in the country this year, more than double previous estimates. The Swedish Migration Agency expects an estimated 33,000 unaccompanied children and says it will need an additional 70 billion Swedish krona ($8.4bn; £5.4bn) over the next two years to cope with arrivals

More than 12,600 migrants crossed into Slovenia from Croatia on Wednesday, and 5,000 by noon on Thursday, bringing the total to more than 34,000 people since Saturday. Migrants began flowing into Slovenia late last week on their journey to northern Europe after Hungary closed its borders

German police said they foiled a planned attack on a refugee home in Bamberg, southern Germany by a right wing extremist group. The news came as German police said there had been nearly 600 attacks on refugee homes this year, a sharp rise from 2014

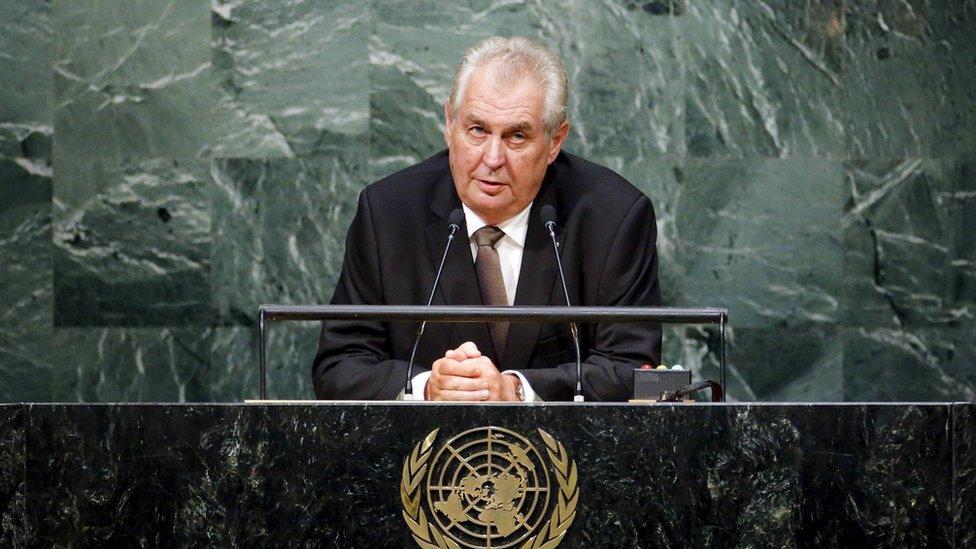

Czech President Milos Zeman has come under fire for his comments on Muslim refugees

While other European countries had implemented policies to restrict the movement of migrants, the Czech Republic was "unique" in its routine detention of migrants for long periods, Mr Hussein said in a statement, external.

He said the measures taken appeared to be "designed to deter migrants and refugees from entering the country or staying there".

Mr Hussein said one detention facility in Bela-Jezova has been described as "worse than a prison" by the Czech justice minister.

He added he was alarmed by the "xenophobic" public discourse in the country, including statements by Czech President Milos Zeman.

Refugee advocates were outraged last month when images emerged of Czech police inking numbers on migrants.

'A stinging rebuke' - Rob Cameron, BBC Prague correspondent

Mr Hussein's words are the most damning indictment yet of the Czech Republic's policy of routinely detaining migrants. His claim that refugees were systematically held in degrading conditions to deter others from seeking asylum is a stinging rebuke.

Czech PM Bohuslav Sobotka defended his country, saying conditions in detention facilities were improving and that the criticism was "misplaced". "The Czech [Republic]has been striving - not just now but for some time - to respect international conventions," he added.

Meanwhile the response from the president's office to Mr al-Hussein's criticism of President Zeman's 'Islamophobic' remarks was swift and uncompromising. "This verbal attack on the president is not the first," his spokesman wrote on Facebook, claiming it was part of an "intensifying" campaign against the Czech Republic.

Mr Zeman recently warned Muslim migrants would not respect Czech customs and would bring with them Sharia law. "The beauty of our women will be hidden, as they'll be forced to wear burkas," he recently said. "Though I can think of some for whom this would be an improvement," he added.

Boorish comments like this play well with a certain section of Czech society, which is - in general - hostile to the idea of accepting Muslim refugees. And Mr Zeman could well be standing for re-election in just over two years' time.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published2 September 2015