Ukraine conflict: Guns fall silent but crisis remains

- Published

Ukrainian forces (above) and pro-Russian rebels have begun pulling their tanks back from the frontline

Since Russia embarked on its foreign policy venture in Syria, you could be forgiven for thinking that the crisis in eastern Ukraine was over.

The guns have largely fallen silent, more than 18 months after Russia annexed Crimea and pro-Russian rebels took control of large areas of Donetsk and Luhansk.

The diplomatic language has become more positive.

Russia's Vladimir Putin and President Petro Poroshenko of Ukraine met in Paris earlier this month and, shortly afterwards, local elections planned in the rebel-held east were postponed.

The planned vote in rebel-held territory had threatened to derail negotiations involving the rebels.

But now there are regular reports of both sides withdrawing weapons from the frontline.

For the region's civilians, it marks a dramatic change in their lives.

Tom Burridge reports on the humanitarian situation in eastern Ukraine

But behind the ceasefire agreement reached in the Belarusian capital, Minsk, between the so-called Normandy Four (Ukraine, Russia, Germany and France) intractable and seemingly insoluble issues remain.

Even before you get into the detail, things do not look good.

'Fascists'

The language from the rebel leadership in eastern Ukraine is uncompromising.

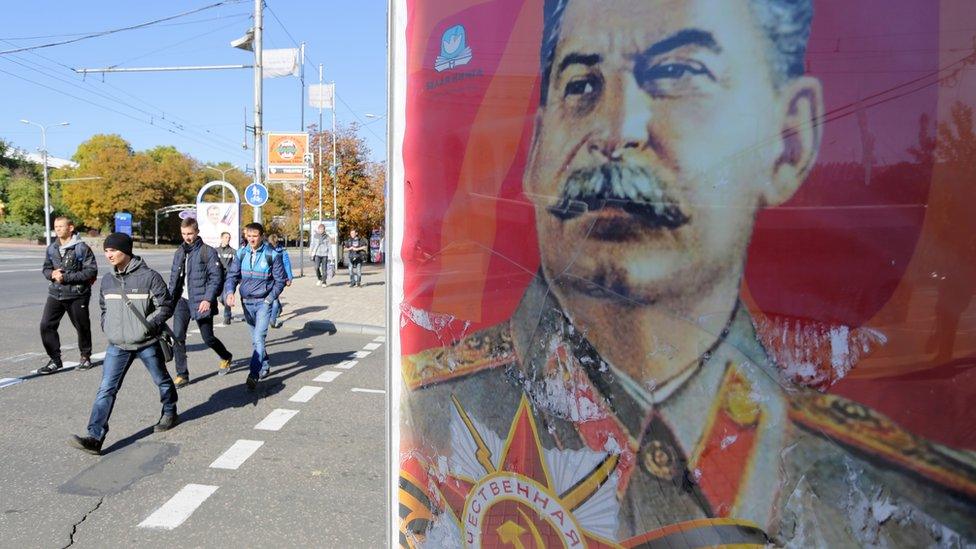

Rebel leaders have for months been telling the local population they have been fighting "fascists"

"There's more chance of Ukraine becoming part of us than of us returning to Ukraine," the leader of the pro-Russian self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic, Alexander Zarkharchenko, told the BBC recently at a propaganda-fuelled event to honour the rebels' war dead.

He and the pro-rebel media machine have spent the past few months telling the local population who didn't flee that they are fighting "fascists", in the form of Ukraine's army.

A sudden change of tone would risk a loss of credibility.

However the rebels are not a homogeneous bunch.

Denis Pushilin, who has represented the rebels in the Minsk talks, is seen as more moderate and possibly more willing to do business with Ukraine than Mr Zakharchenko.

Buying time

The most fundamental part of the Minsk agreement is that rebel-held land has to be re-integrated back into Ukraine, albeit with more autonomy from Kiev. The detail of this is yet to be worked out.

Even though it is positive that the rebels' have postponed their elections, probably with some prompting from Moscow, a later date only buys time.

The detail still needs to be worked out.

Who will police the elections? Kiev says the rebels, who it deems to be "terrorists", would have to disband and submit to Ukrainian law.

Which parties will stand in a poll? A senior member of Ukraine's government recently told me there was no chance of an amnesty for the pro-Russian rebels whom he termed "criminals".

Then there is the issue of who is able to vote in the elections.

The Ukrainians want all those people who have fled rebel territory to have the right to return or at least to vote.

We are talking about hundreds of thousands of people.

Many are in Russia and the Moscow government would like them to be able to vote, remotely, from there. Ukraine says no.

The Brits who joined the pro-Russian rebels - outsiders lured by fight against "Western imperialism"

Odessa leads Ukraine's battle for reform - foreign experts head to southern Ukraine to fight corruption

In theory, after elections, Ukraine should retake full control of its side of the border with Russia.

However, again, this would be tantamount to the rebels switching off their own life-support machine.

So is the Minsk ceasefire deal simply an act of political pantomime and is President Putin writing the script?

Maybe. Talk of Moscow withdrawing financial, political and alleged military backing for the rebels is unfounded and, for now, based mainly on rumour.

Russia would like the EU to lift sanctions to help its stuttering energy-dependent economy.

Many Ukrainians believe Mr Putin is keen to show willing to get sanctions dropped.

They fear France and Germany, with more pressing problems such as the influx of migrants and refugees, might accept gestures from Moscow without a binding deal that returns full sovereignty over the east back to Kiev.

But the accusation of political pantomime might be levelled at Kiev too.

The economy and infrastructure in the rebel-held east have been ruined by the conflict.

There seems little chance that cities like Donetsk will be re-integrated into the rest of Ukraine any time soon

President Poroshenko has to appear committed to retaking the east, facing a threat from opposition parties and local elections due in Ukraine on Sunday.

Any sign that Kiev has given up on the region might risk provoking nationalist groups who might feel that their fallen comrades died for nothing, if the east is simply surrendered.

But there seems little chance that the east might be re-integrated into the rest of Ukraine without a change of government in Moscow.

So the chances are that a so-called "frozen conflict" may persist, where the fighting is at a low level, but the threat of escalation remains.

For now the firing has stopped in the east, but the conflict is nowhere near over.

- Published19 October 2015