Fears the banlieues could burn again

- Published

Aulnay-sous-Bois was among the suburbs to experience violent unrest

It is exactly 10 years since the start of France's banlieue riots - the three weeks of violent street protest in the high-immigration suburbs, sparked by the accidental deaths of two teenagers after a police chase.

Plenty of money has been pumped into the banlieues - but has anything really changed?

It is with a depressing sense of familiarity that one reads this week the 10-year post-mortems on France's 2005 riots.

Everyone concedes that after the shock a lot was done to regenerate the "lost" neighbourhoods of Clichy, Grigny, Bobigny, et cetera.

Some 48bn euros has been spent in the past decade alone to rebuild housing and smarten up the "urban fabric".

To this can be added a further 100bn euros spent since the start of the 1980s, when the problem of disaffected suburban zones was first identified.

But by now everyone also agrees that money is quite evidently not the answer. If it was, this crisis would have been solved long ago.

For the depressing fact remains by just about every recognised criterion, the banlieues (or to be clear the large areas within city suburbs where populations mainly of north African and sub-Saharan origin live in blocks of council flats) are today in the same sorry state as before. If not worse.

Taxed income is 56% of the national average.

Unemployment rates among young people hit 50%. Crime is far more prevalent than elsewhere.

Only last weekend in the northern suburbs of Marseille, three people were killed in an apparent drugs-related shootout, external. Two were boys of 15.

Declining public image

In addition, the image of the banlieues in the eyes of the rest of the country continues to decline.

In a poll just out, the most common adjectives used were:

poor

badly maintained

dangerous

divided by community

More than six people in 10 agreed with the statement that "most of the time, young people in the cites [council estates] behave worse than others do".

Seen the other way, people from within the banlieues still complain bitterly of stigmatisation and stereotyping.

As Thomas Guenole, author of Do Banlieue Youth eat Children?, puts it: "When you grow up in the banlieue, discrimination comes three ways: when you apply for a job, when they see your address, when they look at your face."

So far, so familiar.

But there is one area, of course, in which the past 10 years have seen a big change in the banlieues - and that is religion.

When the riots broke out in October 2005, there was near universal agreement that the root of the problem was social: poverty and discrimination were the causes.

To say otherwise - to imply there might also be a cultural element linked to colonialism, Islam and an inherited rejection of France - was to risk accusations of racism.

Ten years on, the debate on this issue is much more open - and furious.

Islam as a factor

What has happened during that decade is the emergence of Islam as a larger factor in determining how people behave.

Mostly, the signs are of a quietist, pietist nature: dress-codes on the street, higher attendance at mosques.

Riots broke out in other cities, such as Toulouse

But there has also been the growth of Islamist attacks.

From Mohamed Merah, external in Toulouse to the Kouachi brothers , externaland Ahmedi Coulibaly and the hundreds who have gone to Syria - these are French citizens willing to attack France out of a higher loyalty.

The militants are a tiny minority - and not all are from the banlieues - but most are indeed from the same poor, crime-ridden milieu.

As Malek Boutih, a Socialist deputy from the southern Paris banlieue, put it this week: "We have been on a downward slide which has led to the point where our neighbourhoods produce terrorists. Ten years ago it was rioters, now it is terrorists."

For many left-wing analysts, to talk of Islam in relation to the banlieues remains problematic.

Sylvia Zappi, a journalist for Le Monde, argues that by replacing a hoodie with a religious fanatic, the French have merely gone from one unrepresentative cliche of a baddy to another.

Thomas Guenole says that focus on a radicalising minority conceals the fact that "the great mass are moving away from Islam".

But others - mainly but not just on the right - talk of a new and worrying phenomenon: of not just a failure of integration, but of dis-integration, dis-assimilation - for the first time of people moving away from the social body.

Is a repeat possible?

So 10 years on, could the 2005 riots happen again?

It would be foolhardy to argue otherwise.

France 2005 riots:

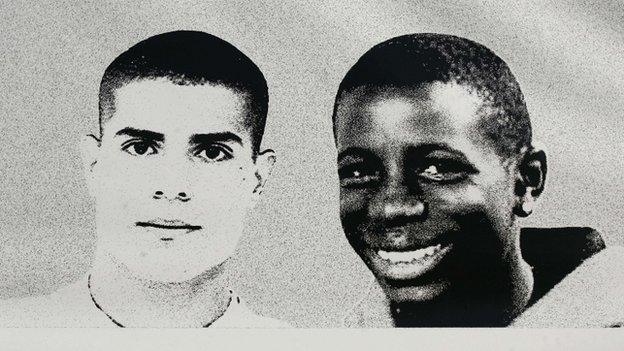

The deaths of Zyed Benna (L) and Bouna Traore led to 21 days of rioting across France

25 October: Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy pelted with stones and bottles in Paris suburb of Argenteuil. Describes violent elements as "gangrene" and "rabble" ("racaille" in French)

27 October: Deaths of Zyed Benna and Bouna Traore in Clichy-sous-Bois trigger riots. The boys were electrocuted after hiding from police in a sub-station

30 October: Mr Sarkozy pledges "zero tolerance" of rioting and sends police reinforcements to Clichy-sous-Bois

3 November: Violence spreads beyond Paris region to eastern city of Dijon and parts of South and West

8 November: President Jacques Chirac announces a national state of emergency - the first time since the Algerian War nearly 50 years earlier

9 November: Emergency powers come into force across more than 30 French towns and cities. In total nearly 3,000 arrests were made and nearly 9,000 vehicles were burned during three weeks of riots

The bored young men are there, more than ever.

The economic crisis is deeper. Relations with police are terrible.

The growth of the Front National smoothes the belief that France is racist, so hitting back is fair.

Ten years ago - after the riots - the historian Georges Bensoussan edited a book called The Lost Territories of the Republic.

Nicolas Sarkozy was Interior Minister at the time of the unrest

The book has just been reissued, prompting this observation from the author in an interview:

"I was struck by how, for many of the people I spoke to recently, the words 'civil war' - which they would have laughed at 10 years ago - were now a phrase they were prepared to use.

"I am talking about police, medical workers, local politicians, people of the banlieue. The feeling that there are two peoples being formed, side by side, looking at each other with hostility - that feeling is shared by many."

Depressing indeed.

- Published18 May 2015