Poland returns to conservative roots with Law and Justice win

- Published

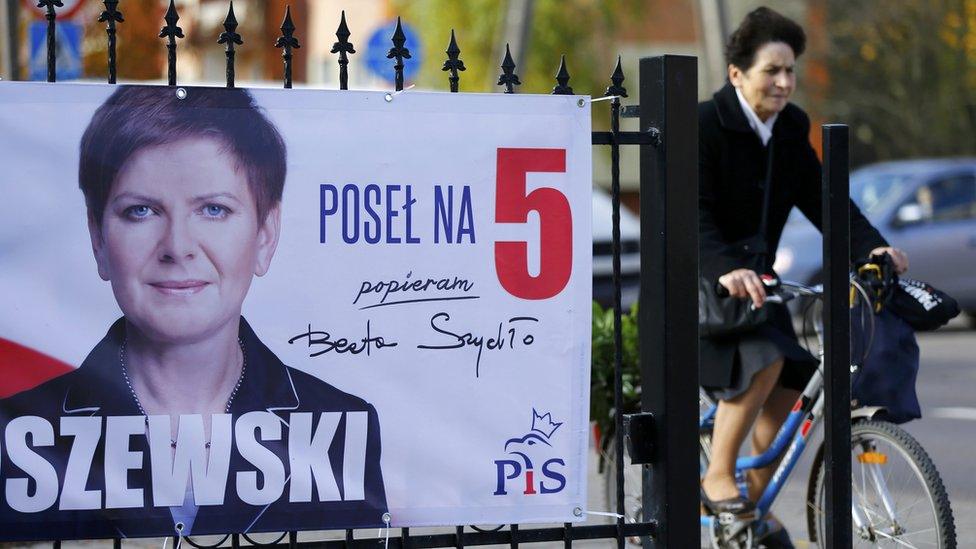

Prime Minister-in-waiting Beata Szydlo espouses traditional Catholic values

A Law and Justice-governed Poland looks likely to be a mildly Eurosceptic, more inward-looking, socially conservative country.

Based on its current policies and its previous term in office from 2005 to 2007, a Law and Justice government will occupy itself more with domestic issues than foreign ones.

Although Poland's economy grew by almost a third during eight years of centre-right Civic Platform rule, the prosperity was spread unevenly.

Some parts of Poland have already reached Western European standards, but other parts are much poorer.

Youth unemployment is above the OECD average - an international benchmark figure - and many graduates see few prospects for themselves.

Poles can still earn much more in the UK or Germany and, while freedom of movement remains, they will continue to seek better-paid jobs abroad.

New tax plans

Law and Justice tapped into this discontent. It promised increased childcare benefits, tax breaks for the less well-off and small businesses, as well as free medicines for those over 75.

It plans to undo Civic Platform's unpopular reform to increase the retirement age for both men and women, and draft a law that will help the more than half a million Poles who took out a mortgage in Swiss francs and now face spiralling repayments.

Law and Justice plans to pay for all this with a new tax on banks, tax big mainly foreign-owned supermarkets and improve collection of sales tax (VAT).

However, improving tax collection would surely not be enough to cover a programme predicted to cost more than €10bn (£7bn; $11bn) a year. Some critics argue the plans will never be realised.

A Law and Justice government will likely occupy itself more with domestic issues than foreign ones

While there are concerns about a move towards more populist policymaking, the impact on the economy in the short term will be fairly limited, some analysts reckon.

Higher spending on social welfare "could boost GDP growth over the next few years", wrote William Jackson, senior emerging markets economist for Capital Economics.

But that could be undermined by Law and Justice's lack of appetite for structural reforms, he warned. And that "may lead to weaker investment and productivity growth, slowing down the process of income convergence with European peers".

In social policy a Law and Justice Poland will certainly be more conservative than many Western European countries. It opposes civil partnerships, afraid that homosexuals might somehow get the right to marry and adopt children.

It may stop public funding for married heterosexual couples seeking IVF treatment to start a family. Schoolchildren will be encouraged to be more patriotic.

Tensions with Brussels

Internationally, Warsaw will look to strengthen alliances with its neighbours in Central and Eastern Europe. Civic Platform's policy of influencing European Union policy through close ties with Germany will likely be shelved.

Indeed it will be interesting to see if the mildly Eurosceptic Law and Justice will take a constructive approach to shaping policy in Brussels. Law and Justice's anti-immigrant stance looks likely to set it at odds with the European Commission over migrant quotas in future.

This year saw the fifth anniversary of the presidential plane crash in Smolensk in which Lech Kaczynski died

Law and Justice has traditionally looked to Washington in defence policy, and while it has promised to increase its own military spending to 2.5% of GDP, it would like to see Nato locate significant bases in Poland - an issue where Warsaw and Berlin differ.

Warsaw's already dire relations with Moscow are unlikely to improve. Poland's former President Lech Kaczynski, the identical twin of Law and Justice leader Jaroslaw Kaczynski, died in a plane crash in Smolensk, western Russia, in 2010.

Poland is still trying to get the plane wreckage back.

Although Mr Kaczynski has vowed not to seek revenge on his political opponents, there may be an attempt to conduct a final reckoning of the Smolensk tragedy.

Mr Kaczynski has actively encouraged wild conspiracy theories that the plane was brought down by a plot, not by pilot error as both the Russian and two Polish investigations have so far found.

Who holds power?

Finally, there is the question of power and where will it truly reside? After losing every election since 2007, Mr Kaczynski was shrewd enough to put up the moderate and unknown MEP Andrzej Duda as his candidate for president in May this year.

The tactic worked and he repeated it by nominating Beata Szydlo as candidate for prime minister. They are the fresh moderate faces of Law and Justice.

But the party is dominated by Mr Kaczynski and it is more than likely that he will be taking the important decisions facing the country in the coming years.

- Published26 October 2015

- Published26 October 2015

- Published26 October 2015

- Published26 October 2015

- Published20 January