Migrant crisis: Hungarian jails crowded by 'illegal' refugees

- Published

How migrants have ended up in Hungarian prisons

More than 1,000 refugees, most of them from war zones in Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, are detained in overcrowded Hungarian prisons or detention facilities.

As of 10 November, almost 700 had been sentenced to expulsion by Hungarian courts for crossing the razor-wire fence along its southern borders.

More than 200 others are detained, awaiting trial. Around 500 people are in asylum detention, a separate category under Hungarian law.

The Serbian government is refusing to accept most deportees from Hungary, in protest against the fence.

Some of the detained migrants are held in this prison at Vac, west of Budapest

The growing backlog means that for the first time in modern Hungarian history there are now more refugees in detention than in open camps, according to the UN refugee agency.

The imprisoned migrants are angry, with little prospect of release and no idea how long they will be locked up.

'Migrant threat'

There have been disturbances in at least one of the 12 facilities where they are held. Privately, Hungarian prison and police officials say they don't know what to do with a problem dumped on them by the government's anti-migrant policies.

"The people have decided - the country must be defended," reads the Hungarian government poster.

It is everywhere in Hungary now - on giant billboards on the roadsides, on bus-shelters, and on websites supportive of the ruling conservative Fidesz party.

In May and June all eight million voters received the national consultation on immigration and terrorism. Just one million papers were returned.

Almost all agreed with 12 leading questions which suggested that the migrants were a threat to work, health and national security. The exercise was a key element in the government's policies to claim public support for the border fence and criminalise those who crossed it.

More on the migrant crisis

The fence on the Serbian border was completed on 15 September, and on the Croatian border on 16 October.

This has deflected most migrants westwards, through Croatia and Slovenia, but a steady trickle continue to cross the fence, either because they are tricked by traffickers into believing it will be safe, or because they are impatient to get to Western Europe by the shortest possible route.

Those caught are arrested and charged.

"You won't try anything, will you?" asks the burly policeman, as he clicks the handcuffs back on the wrists of an Afghan who has just been banned from re-entering Hungary for two years by a court in the border town of Szeged.

The man hurriedly assures the officer, through an interpreter, that he will go quietly. Then he is led away by three policeman, down a busy street, to the Migration Office, before being sent into detention to await expulsion.

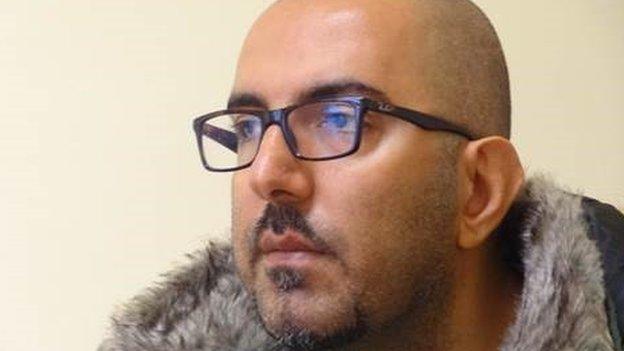

"There is no justice in Hungary," says captured Syrian refugee Samer Kayssoun

The next day it is a similar story in the main county court in the centre of Szeged. Samer Kayssoun is 38, his nephew 17. Both are from Homs in Syria.

Political trials

Ignorance of the new Hungarian law is no excuse, says the prosecutor. The court-appointed defence lawyer says little.

Some lawyers in Szeged have refused to take part in what they regard as political trials, but most are glad of the work.

The trials take place seven days a week. Few last more than an hour. Of nearly 700 accused so far, all except two were sentenced to deportation.

Other criminal cases have been postponed or sent to other courts while 130 judges adjudicate in the trials.

Samer Kayssoun hears the guilty verdict from a judge at the Szeged court

In a break in court proceedings, I ask the judge whether he knows that none of his sentences can be carried out; that everyone ends up in jail anyway, because they cannot be expelled.

The execution of the sentence is not his competence, he says.

Refugees caught in Hungary are tried and sentenced to deportation - but are then left languishing in jails

'Not our responsibility'

On a bench in the corridor I exchange a few words with Samer Kayssoun. "There is no justice in Hungary," he says, "it's just like Syria."

We return to court. The judge reads the verdict. Expulsion from Hungary, banned from re-entering for two years. Samer and his nephew are led away. There are no laces in his shoes - to prevent him from hanging himself for seeking asylum in Europe.

My requests to the Hungarian prison service to be allowed to visit some of those being held are rejected on the grounds that "we are just providing facilities for them, they are not our responsibility".

The police suggest I contact the Migration Office. The Migration Office refers me to the Prison Service. Under Hungarian law, they can be held for up to a year in prison.

"People do not know how long they have to stay there. This is an absolutely disproportionate sanction, disproportionate punishment," says Erno Simon, spokesman for the UN's refugee agency, the UNHCR, in Hungary.

A government spokesman, Zoltan Kovacs, disagrees.

"These people are coming from safe countries. The Geneva Convention wouldn't apply because they are not coming from a country that is being torn apart by war."

He argues that their lives are not in danger. "The security perimeter of the Hungarian border is a clear indication that if you try to cross that, it's illegal."

- Published11 November 2015