Links to Lenin: The past Swiss villagers tried to forget

- Published

Soviet schoolchildren sent postcards to Zimmerwald asking for information about Lenin

On a crisp autumn day in 1915, 38 ornithologists gathered in the tiny Swiss village of Zimmerwald.

Only, they were not actually bird watchers - that was just a cover. These were socialists from all over Europe, meeting to discuss ways to bring peace to a continent ravaged by World War One.

Two of the most famous participants were Russian: Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, or Lenin, and Leon Trotsky.

Their peace campaign made secrecy necessary: opposing the war was viewed as treason in many countries.

Lenin and Trotsky were already political refugees. They were both living in neutral Switzerland - Trotsky in Geneva and Lenin in Berne, quietly planning the overthrow of Tsarist Russia.

Birthplace of a revolution

Today, Zimmerwald is not much changed from that day in 1915.

It is a sleepy little place, population 1,100, with a few farms, a church, and the Alps soaring majestically across the valley.

And for 100 years there was no sign that the founders of the Bolshevik Revolution had ever set foot there.

Until recently the residents of Zimmerwald strongly resisted any official recognition of the village's historical Soviet links

Thousands of kilometres to the east, however, Zimmerwald gradually became famous.

In classrooms across the Soviet Union, the village was being celebrated as the birthplace of the revolution.

"In the Soviet Union, Zimmerwald was such a famous place. Every Soviet school child knew about Zimmerwald," explained Julia Richers, a historian at Berne University.

"But you can ask any Swiss school child, they would never know what Zimmerwald was about."

Zimmerwald conference

Held in Zimmerwald, Switzerland, from 5 to 8 September 1915

Attended by 38 socialist delegates from across Europe

Aimed to bring an end to WW1 through civil revolt

First of three conferences, subsequently held in Kienthal and Stockholm, jointly known as the Zimmerwald movement

Julia describes Switzerland's attitude to its history as a kind of "forceful forgetting", especially in Zimmerwald itself, where, in the 1960s, plans to have a small plaque marking Lenin's presence were formally banned by the village council.

Switzerland's neutrality probably lies at the root of that reluctance to acknowledge the past.

During the Cold War the Swiss were extremely nervous about showing overt friendliness to either East or West, and spent billions on a vast army and on bunkers for every family, in the hope of sitting, neutrally, out of any future conflict.

But in Zimmerwald, reminders of Lenin's presence were dropping through the letter box every day.

Letters from schoolchildren

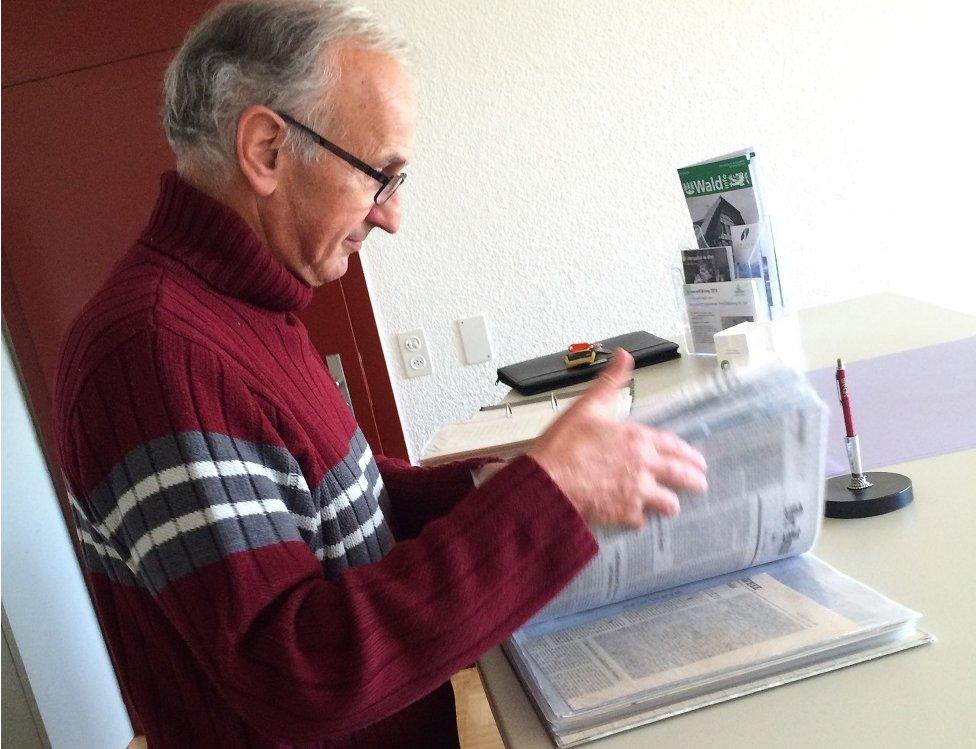

Mayor Fritz Broennimann has a vast archive of earnest missives: postcards, drawings, and notes, from hundreds of Soviet schoolchildren, many of them addressed to the "President of Zimmerwald", all begging for information about their national hero Lenin.

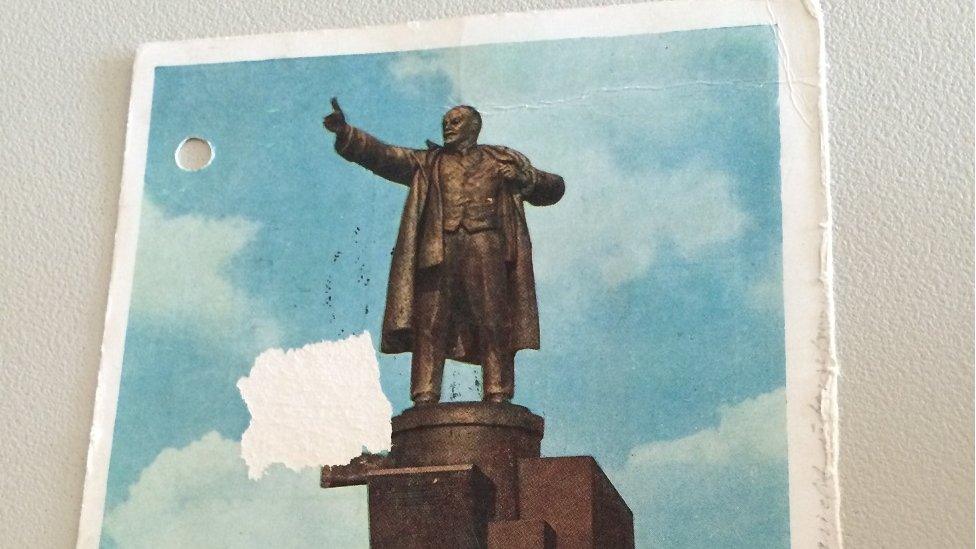

"They asked for photographs, for booklets," he explained, showing a fraying postcard of a Lenin statue in Moscow.

"Some even sent their letters to the Lenin museum in Zimmerwald."

Of course, there was no museum, and there were no photographs or booklets.

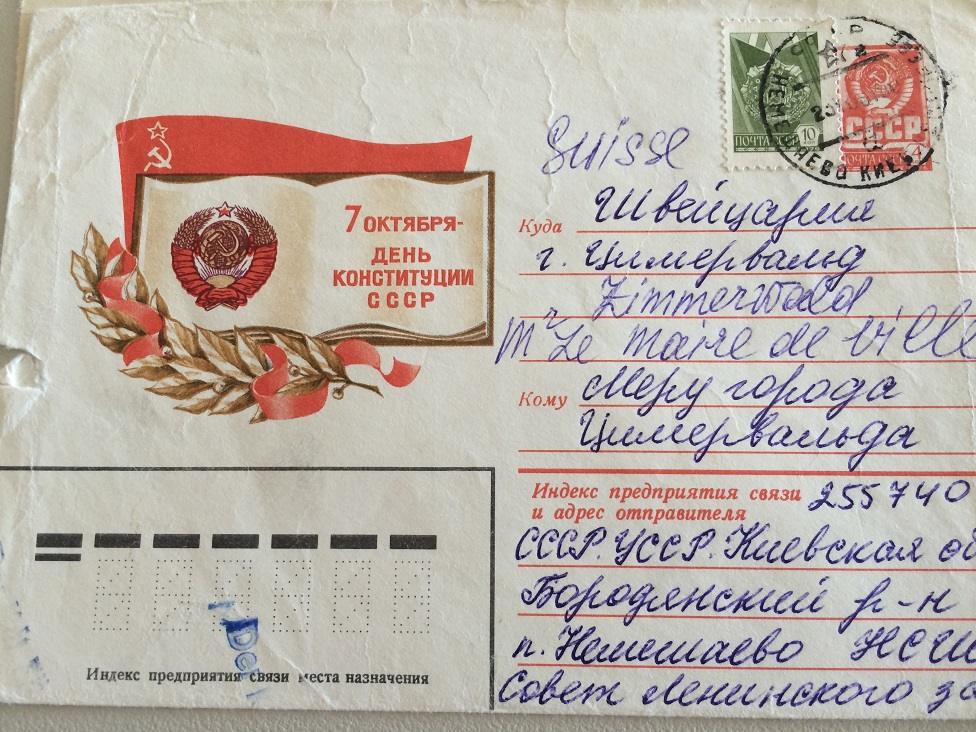

Zimmerwald officials received large amounts of post with Soviet stamps

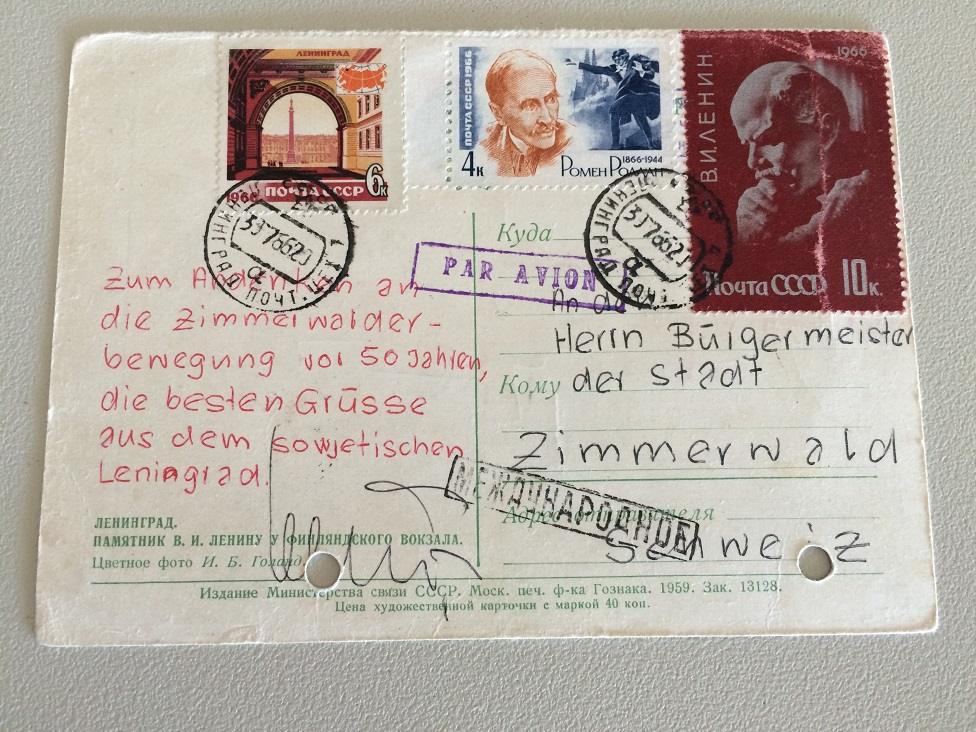

This postcard was sent "in memory of the Zimmerwald movement 50 years ago" with "best regards from Soviet Leningrad"

Most of those letters were never answered.

But occasionally a Zimmerwald official, perhaps made anxious by the excessive amount of mail with Soviet stamps landing on his desk, tried to stem the flow.

And so, in 1945, this firm reply was sent:

"Sir, I have not been briefed on your political sympathies. However, I am not inclined to provide material to a political extremist, which could then be of use to enemies of the state."

Mayor Fritz Broennimann keeps an archive of the letters and cards

Even in this centenary year, Zimmerwald has wrestled with the apparently agonising decision over whether to mark it.

"We had an idea [for an article] - 'A hundred years, a hundred opinions'," explained Mayor Broennimann.

"So we put an advertisement in the local paper. We got about six answers."

Lessons of history

But just a few kilometres north of Zimmerwald in the Swiss capital Berne - one of the most left-leaning of Switzerland's cities - the significance of the Zimmerwald conference is getting a good deal of attention.

"Zimmerwald was actually a peace conference," said Fabian Molina, president of Switzerland's Young Socialists party.

"They were young leftists from the whole of Europe, discussing peace, discussing their strategy against war."

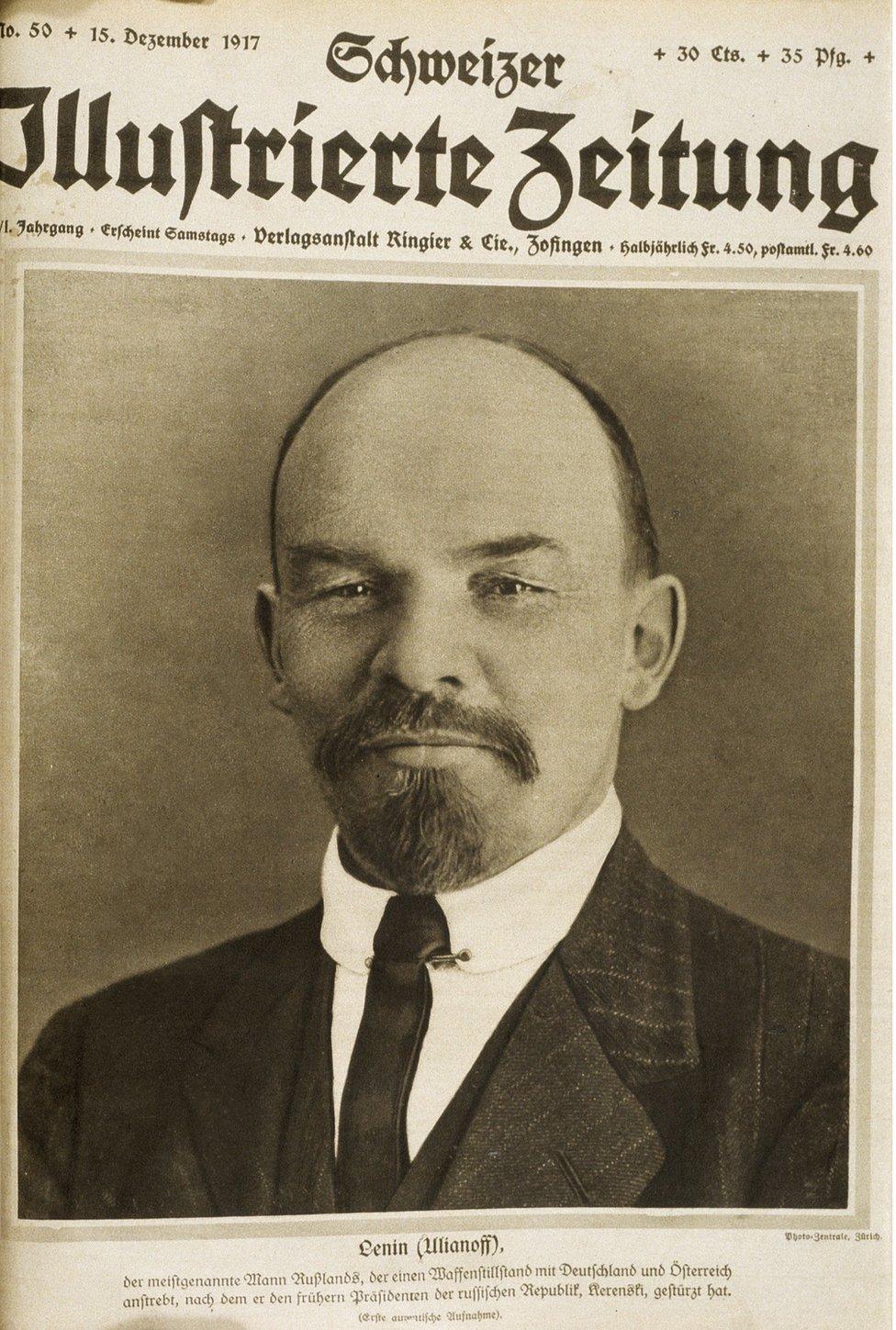

Lenin appeared on the front page of the Schweizer Illustrierte, a famous Swiss weekly news magazine, in December 1917

"A hundred years after Zimmerwald, we are in a similar situation, if we compare the wars that are going on, with 60 million people fleeing.

"We have a refugee crisis, it reminds us how violent the world is, and so it's important to remember there was once a conference of people uniting for peace."

Historian Julia Richers agrees, pointing out that the conference was the only gathering in Europe against the war, and that the final manifesto from Zimmerwald contained some fundamental principles.

"The Zimmerwald manifesto stated three important things," she explained. "That there should be a peace without annexations, a peace without war contributions, and the self-determination of people.

"If you look at the peace treaties of World War One, those three things were hardly considered, and we know that World War One led partially to the World War Two, and so I think the manifesto did state some very important points for a peaceful Europe."

A little-known fact is that that manifesto was not revolutionary enough for Lenin and Trotsky, who wanted it to contain references to replacing war between nations with an armed class struggle.

Their fellow socialists and social democrats in Zimmerwald outvoted them, but Lenin continued to harbour hopes that Switzerland might be fertile ground for staging a revolution.

"He once stated that the Swiss could have been the most revolutionary of all, because almost everybody had a gun at home," said Julia Richers.

"But he said that in the end the society was too bourgeois… so he gave up on the Swiss."

"I think he recognised after a few years that it was not a good idea to start a revolution in Switzerland," laughed Fabian Molina.

"Switzerland has always been a quite right-wing country, it… never had a left majority, and I think Lenin saw that the revolutionary potential here in Switzerland was quite small."

Recognition at last

But back in Zimmerwald, that historic conference, and its most famous participants, have finally received some modest recognition.

On the spot where the hotel Lenin stayed in once stood (it was pulled down in the 1960s to make way for a bus stop) are two small signs.

Made only of plywood and cardboard, they will not last once winter begins, Fritz Broennimann admits, but they do at least commemorate the events of 1915.

One of two simple, temporary signs, marking the spot where the hotel Lenin stayed in once stood

And, after much discussion, the village held a memorial event, with speeches by historians and politicians.

It took place in the local church which, Mr Broennimann remarks with a wry smile, "was full for a change".

And Lenin? He carried on living in Berne, where he wrote some of his most important political treatises.

In 1916 he moved to Zurich, and in early 1917 he took the famous train from Zurich to St Petersburg, which was teetering on the edge of revolution.

The rest, as they say, is history.

- Published10 September 2015

- Published9 November 2015

- Published19 March 2011

- Published31 October 2013