Paris attacks turn spotlight on Saint Denis banlieue

- Published

Saint Denis is a multi-ethnic banlieue, where much of the population has a "sans-papiers" status

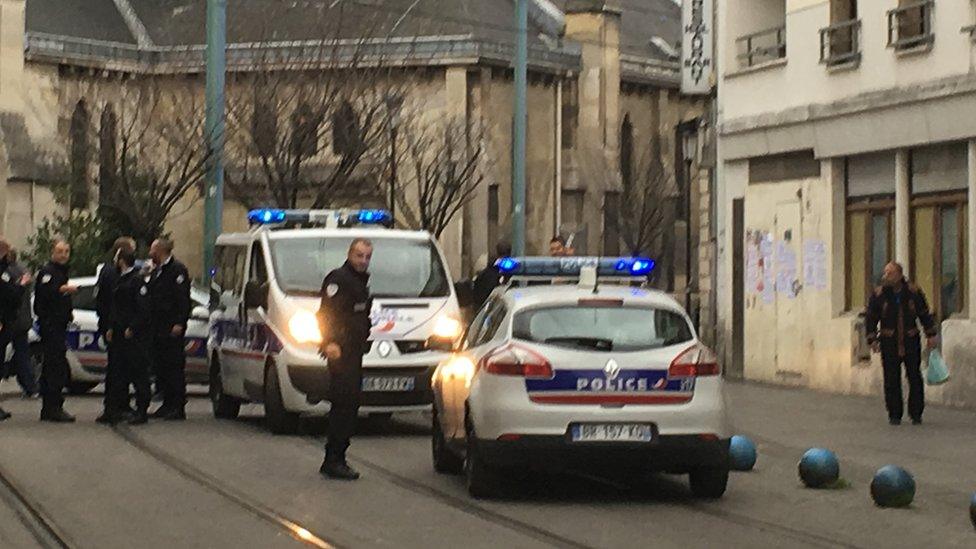

Saint Denis was in lockdown as a police operation unfolded against suspects in Friday's attacks, and the latest developments moved the focus to this northern Paris suburb at the heart of France's debate over radicalisation.

While Parisians warily return to the cafes, restaurants and theatres, the mood among young people in this banlieue - less then a 30-minute train-ride away - is a far cry from the fun lifestyle that epitomises the central districts.

Around the Place de la Republique in central Paris, streets away from last Friday's deadly attacks, all the talk is of solidarity. But in Saint Denis, it is different.

"Right, solidarity… But don't you think they exaggerate the Paris attacks when there are more Syrians dying everyday?" This is what I heard in Saint Denis, a multicultural and multi-ethnic place with a population of Africans, Algerians, Indians, Chinese, Turkish and many other backgrounds.

Many here have a "sans-papiers" status, without legal status or an ID that would allow them to work.

Crime is rife, with high rates of robbery, drugs offences and murder.

'Mobile kebab shops'

The first thing you notice outside the station is the supermarket trolleys with a little makeshift brazier on top.

Mainly run by African French locals, these are "mobile shish kebab shops" on wheels apparently to help them flee police more quickly.

Celine (left) fears there will be a another world war

There are no bistros here but there is a variety of restaurants, halal butchers and Maghreb sweets.

Chinese stores sell all types of gadgets while boutiques display glittering, sequined, frilled and lacy nightdresses along the main rue de la Republique.

'Nothing we can do'

Celine and her friend Lemea are both 17 and part of the banlieue generation.

When I ask about the Paris attacks, Celine blames French government policy.

"I think there will be a third world war. But France has been asking for it because of its intervention in Syria," she says.

"The Paris attacks lasted three hours - but this happens everyday in Syria. And Palestinians are dying, too.

"A quarter of Paris says: 'Pray for the French, pray for Paris' - but they don't do it for Palestinians. They have called for solidarity with the Palestinians for some time - but they did it as if it was fashionable."

Atek says he is not shocked by Paris attacks, pointing out that about 160 Syrians die every day

Atek Riles, 19, who works at a halal meat butcher has a similar argument.

Born in Saint Denis, he rarely leaves the area and has little time for the Paris attacks.

"If you look closer at Syria, there are now nearly 250,000 dead there. It is about 160 dead per day. So, I am not shocked by these Paris attacks. They are important, of course. But there is nothing we can do."

Although his suburb has been caught up in the violence, Atek believes anyone who grows up in Saint Denis is not at risk of being indoctrinated by Islamists.

"Those who become radicalised are mentally weak. I used to get upset by what people said about the banlieues, but now I don't even care. They have their lives, we have ours."

'Brainwashed'

Residents here see themselves as separate from the rest of Paris. I frequently hear remarks about "us and them".

That separation from the rest of French society is highlighted by Nilgul, a 29-year-old ethnic Turkish woman born in Saint Denis.

Much of the anger here dates back to France's war in Algeria from 1954-62, in which at least 60,000 Algerian civilians died, she suggests.

"Their problem is not Paris. The reason they're being radicalised might be their desire to take revenge for their parents," she believes.

"But also they are mentally weak. Their weaknesses are being exploited in the name of Islam. They are brainwashed."

Abdullah says his kebab shop was bullet-riddled a month ago by a gunman pursuing his target

Turkish-born Abdullah shows me the bullet holes in his shop, which was hit last month by a gunman chasing his target.

"Virtually no day passes without incident."

"This is the most dangerous place in Paris," says a Moroccan woman, who works as an Arabic translator at the local police station.

Police describe Saint Denis as a "difficult" place to patrol

As I head back to the station, the "mobile kebab shops" are nowhere to be seen. The spot is now occupied by three policemen.

I ask them to sum up Saint Denis.

"Rotten," says one. Then, perhaps regretting his choice of word, he adds: "Difficult, I would say. In a single word, this place is difficult."