Vive la difference - has France's National Front changed?

- Published

Gabriel Gatehouse visits Cogolin in south-eastern France, a key electoral region for the National Front

The National Front (FN) is attracting a new kind of supporter.

Several hundred of them gathered one evening this week in Neptune's Palace, a conference hall in the city of Toulon on the French Riviera, ahead of national regional elections this month.

They waved their Tricolores as they waited for the main event: an appearance by Marion Marechal-Le Pen, the 25-year-old granddaughter of the party's founder.

They booed and jeered as images of France's mainstream politicians were shown on a giant screen.

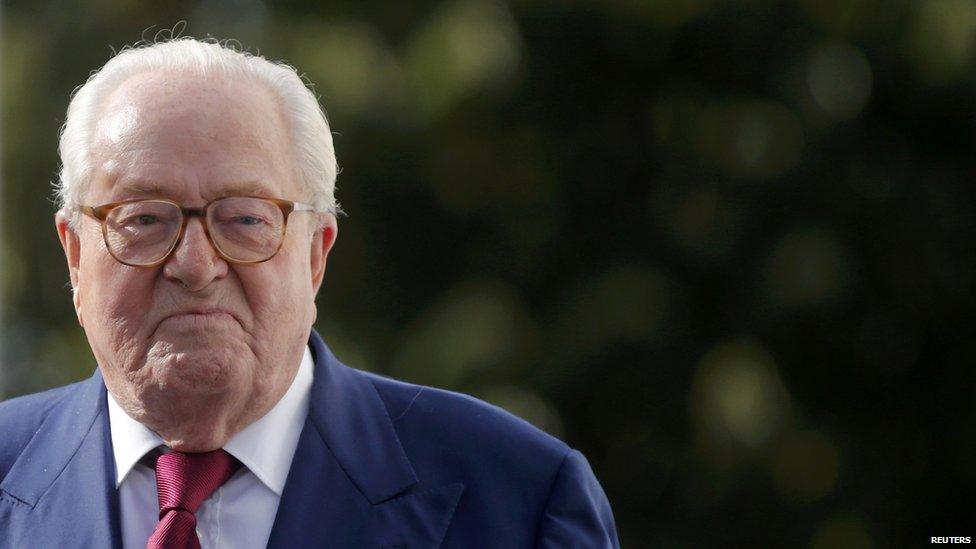

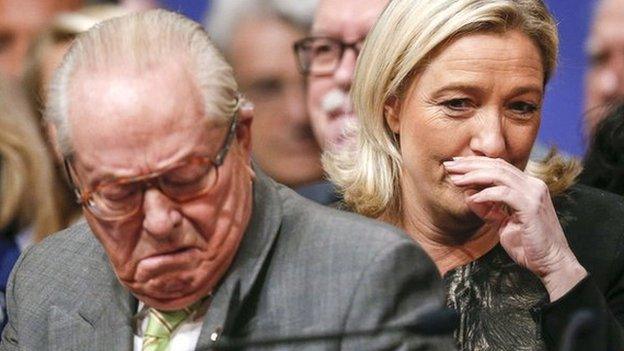

This is a different kind of party from the one Jean Marie Le Pen, a former paratrooper, set up in 1972. There were no skinheads. There weren't many non-white faces either. But this certainly wasn't a gathering of neo-Nazis.

"I was the sort of person who would never even think about [joining], even five years ago," said Philippe Lansade, a businessman in his forties who told me he'd joined the National Front the day after the attacks in Paris last month.

"Having lived in the US, UK, I just can't understand how come you can speak like the Tea Party in the US and you're mainstream politically, or you can have UKIP in the UK and more or less say the same and you're mainstream, and you, as a journalist, dare to ask people like us if we are fascists."

'Terrible lesson'

Jean Marie Le Pen has called the Holocaust a "detail of history". Remarks like this, perceived as anti-Semitic, are severely discouraged on the campaign these days. But anti-Islam rhetoric is commonplace.

Opinion polls suggest the National Front's popularity has risen since the Paris attacks

Marion Marechal-Le Pen: "We are not an Islamic nation"

"We know what we are," said Marion Marechal-Le Pen in her speech.

"And we know what we are not. We are not an Islamic nation."

She spoke of the "terrible lesson" of the 13 November attacks. Afterwards, I asked Ms Le Pen what she thought that terrible lesson was.

"The lesson is that radical Islam has taken shape in certain areas of France due to mass immigration.

"This has created French people who take up arms against the country that welcomed them. So we need to rethink the entire global policy, in terms of border controls, the acquisition of nationality and restricting the flows of migration if we don't want things to get worse."

Read more: Marion Marechal-Le Pen and France's far-right charm offensive

A recent opinion poll suggests the National Front's popularity has increased by between four and seven percentage points since the Paris attacks.

The party's leader, Marine Le Pen (Jean Marie's daughter and Marion's aunt) could win in the northern region of Nord-Pas-De-Calais-Picardie, one of 13 to be contested in two rounds of voting on successive Sundays - 6 and 13 December.

Regional victories could boost Marine Le Pen's campaign for the presidency in 2017

Marion Marechal-Le Pen could win in the southern region of Provence-Alpes-Cote d'Azur.

It would be the first time the National Front has captured any of France's regions.

These "super-regions", while geographically large, are not politically powerful.

But a win or two would be a morale boost to Marine Le Pen's campaign in the 2017 presidential elections.

Current polling suggests she could win the largest share of the vote in the first round then, though few experts currently expect her to win in the second.

Gabriel Gatehouse was reporting for BBC Newsnight, which airs every weekday at 22:30 GMT. Watch his full report here, external

- Published4 December 2015

- Published1 December 2015

- Published28 October 2015

- Published20 October 2015

- Published13 March 2015

- Published6 May 2015

- Published20 August 2015