Spanish election: Resisting change in a dying village

- Published

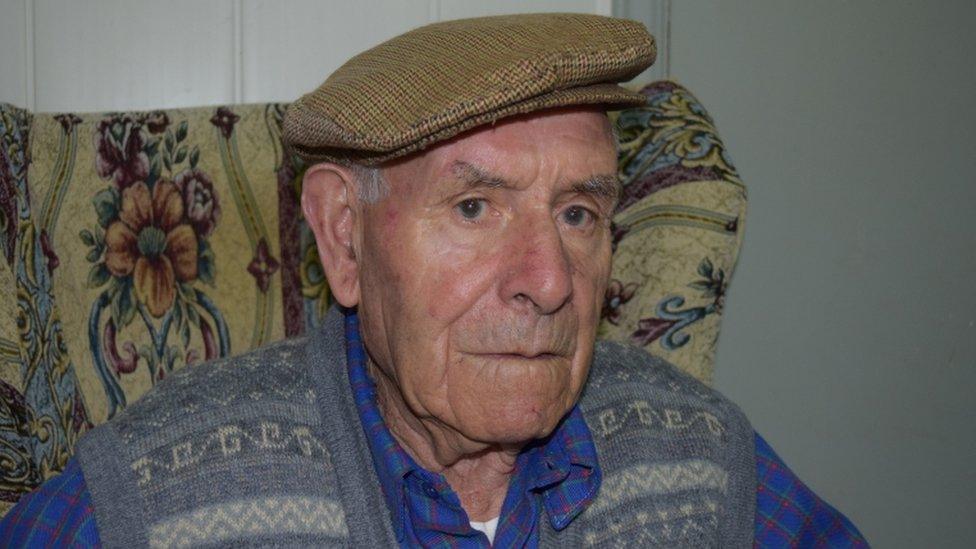

Juan Rio Belver remembers the days when his village teemed with life

When Juan Rio Belver, 66, moved to Casaseca 50 years ago, Sunday afternoons meant bands playing in the square and young couples strolling past on their way to parties.

But all that has changed in this part of north-western Spain. The village population today is 381, nearly half of what it was in 1960 (740) and less than third of what it was in 1900 (1,206).

There are just 21 children aged 10 or younger.

And as voters look to the 20 December general election, one disturbing fact haunts all of Spain. For the first time since 1944, apart from a blip in 1999, more Spaniards are dying than are being born.

A playground stands empty in Casaseca de las Chanas

Memories are still fresh in Casaseca of bare feet and empty bellies from the early years of Gen Francisco Franco's dictatorship (1939-75).

But while civil war and Spanish Flu were the big killers in the last century, now they are longevity in the old, and economic pressure on the young. Spain currently has the 10th oldest population in the world.

Add the continuing loss of Spanish workers to the job markets of northern Europe and beyond, and you have a demographic crisis on track to cut the current population of just over 46 million by a million within 15 years.

This week the BBC will be reporting from across Spain on the issues affecting voters, from Murcia in the south to Castile and Leon and Catalonia in the north.

For its diminishing population, Casaseca punches far above its weight in Spanish politics.

The village mayor, Fernando Martinez Maillo, not only heads the Popular Party (PP) in the province of Zamora, but he is the ruling conservative party's "number three" at national level.

And if most Spaniards voted like Juan and his friends, the PP would be back for a second term after 20 December.

'Worse than Franco'

You could be forgiven for thinking Casaseca was suddenly swinging to the left because the only posters in evidence are for the Socialists and the anti-capitalist Podemos.

Not so, I am informed in one of the cafes. The faces of Socialist leader Pedro Sanchez and Pablo Iglesias of Podemos are apparently only beaming from a wall and some wheelie bins because party activists nipped into Casaseca earlier in the day.

Evidently, the PP does not feel the need to post its colours locally - in total contrast to the city of Zamora itself, 10km (6 miles) up the road.

There, the faces of the village mayor and Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy smile down "in earnest" from lamp-posts, on voters who unceremoniously ejected the PP from power in the May local elections. The PP's slogan is "Spain in earnest".

In fact, Zamora's voters elected a far-left mayor, Francisco Guarido of the Izquierda Unida (United Left) party.

Adding to the Zamora PP's woes, it was announced in the summer that Mr Maillo was under investigation in the neighbouring province of Leon, over allegations (brought by his political opponents) of "unlawful administration" while sitting on the board of directors of the Caja Espana bank.

Mr Maillo commented at the time that the investigation had effectively been suspended.

Out in the Zamora countryside, his PP party can still count on farmers who have little time for political experimentation.

Public benches stand empty in Casaseca

In Casaseca's main square, Juan refers to the PP as the Popular Alliance, the old name from when it was set up in 1976 by Franco's former information minister, the late Manuel Fraga.

He says he supports the party because of the "huge work" it has done to "rebuild the country after the crisis, through a common effort".

But perhaps it could offer tax relief for people living in the country as way to stop depopulation, he suggests.

It was the Socialists, Spain's main opposition, who plunged the country into crisis both times when they were in power, he declares.

"Life was better under Franco than whenever the PSOE [the Socialist party] was in power," he says.

When I ask about the two major newcomers in this election campaign, the liberal Citizens (Ciudadanos) and Podemos, he says: "Young people want to do politics and make changes but they are not ready to govern the people and the country."

Classic conservatives

In the nearby village of El Pinero, where there are 11 children aged 10 or below, Lucio Vasallo Merchan, 88, says he is worried the PP might not win back overall power because of the new parties.

Lucio says he will vote for the PP because it is the "most progressive party" and he has always supported "the right".

"It is the party best able to make money," he says.

Lucio Vasallo Merchan is backing the PP but fears the rise of the new parties

The new parties might have good intentions but "nobody knows what they might do", he adds.

Juan and Lucio, who lived under the dictatorship when these villages suffered their share of repression, represent only part of the PP's electorate, though an enduring one.

For many Spaniards who grew up in the 40 years since Franco's death, the PP exists as a classic European conservative party and that is why they vote for it.

A very different narrative runs in the rural heartland of Andalusia in the far south of Spain, a bastion of the left.

Empty streets

Lucio still farms, hoisting his tiny, bent-over form into his little tractor to work his animals, his vegetables and his vineyard, a model of self-sufficiency.

These days he only works to support himself, offering a plate of his own cured ham, some bread and his own sweet white wine, diluted with fizzy water, when I visit.

The widower blames industrialisation since the 1950s for the depopulation of his native village, but he believes Spain has good times ahead, in part because of its industrial base.

I am told anecdotally that some young people are returning from the cities to live on the land again. But the population of the province of Zamora (182,636 as of July) shrank by 0.83% - a rate of 10 people a day - in the first six months of 2015.

Afterwards I explore the largely empty streets of Casaseca in the chilly December fog, as withered leaves blow off trees on to empty public benches.

A couple of dozen people go into the Roman Catholic church for a Mass led by a priest who arrives by car because he serves other churches in the area too.

There are a few children out and about, but no Christmas trees or garlands are to be seen.

Perhaps it is harder to feel festive in a village of 21 children.

- Published8 December 2015

- Published4 December 2015