Reports of Angela Merkel's demise are greatly exaggerated

- Published

In the village of Stein, just on the edge of the Black Forest, everyone turns out for the Christmas brass band. French horns glint in the lamplight. Everyone sings along, and a rather skinny Father Christmas hands out gingerbread.

A woman with a lined face beckons me over. "I came to live here 43 years ago," she says. "We've been doing this every year, without fail."

But in this traditional corner of Germany, they worry about how the country is changing.

During a break between carols, I get chatting to a couple stood nearby. Connie and Gregor tell me: "There are too many refugees arriving too fast. Actually, we agree with Angela Merkel - we think Germany can do it. But, in the short term, we'll have problems."

Will Germans embrace or shun refugees?

EU migration: Crisis in graphics

Stein is just a half-hour drive from Karlsruhe, where Angela Merkel's Christian Democrats (CDU) are holding their annual party conference and where there's only, in truth, one item on the agenda.

Mrs Merkel's handling of the refugee crisis has unnerved the German public and infuriated MPs - many of whom have demanded a cap on the number of refugees the country is prepared to take.

Germany has taken in more than one million migrants so far this year

Mrs Merkel's role in Europe's migration crisis saw her named Time magazine's "Person of the Year" - but her stance on refugees has not been popular within her own party

'We need to send a signal'

For weeks now, politicians have been muttering the so-called "O word" - Obergrenze - or upper limit. Perhaps it's no wonder. In March, three German states will hold regional elections and anti-refugee sentiment has fuelled growing support for the populist party Alternative fuer Deutschland (AfD).

Paul Ziemiak leads the CDU's youth movement, one of the more vociferously critical groups within the party.

"We want a limitation of some sort," he told me. "We don't want to get into a fight over an upper limit, but we need to send a signal that we want to limit the number of people coming. We don't have to put a figure on it."

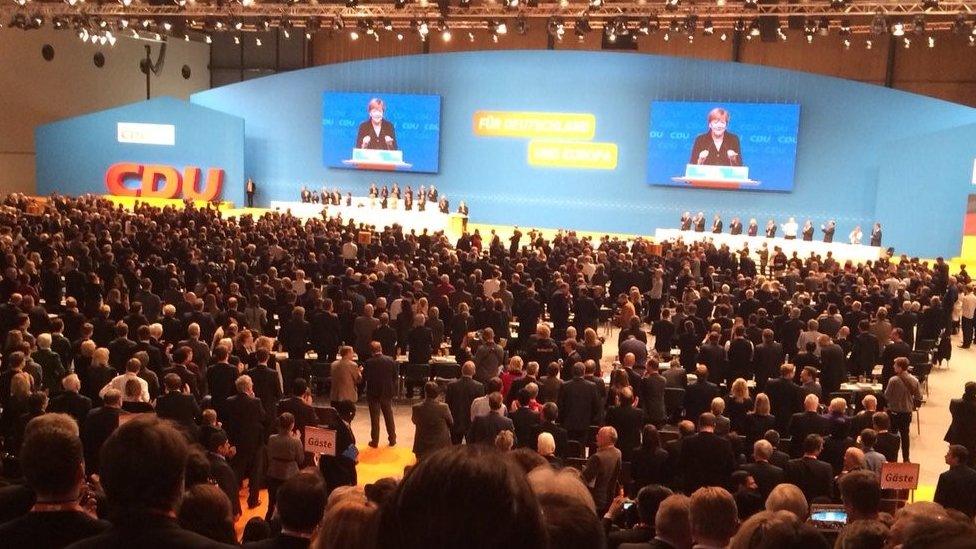

Mrs Merkel used her conference speech to reinforce her refugee policy

Mrs Merkel has resolutely refused to budge. Her open-door refugee policy has cost her approval ratings and, as political criticism has mounted, commentators wondered whether the crisis might be her political undoing.

But on Monday, she faced her critics at the CDU party conference and proved that reports of her political demise were very much exaggerated.

Her 70-minute address included very little that deviated from her policy all along. Germany can still "schaffen es" or "do it". It would not close the door to those in need. Migrant numbers must be reduced but not at national level. The solution to the crisis lies beyond Germany's border, with Europe and beyond.

Defining moment

Yet her MPs loved it. A standing ovation lasted 10 minutes. Mrs Merkel - always a little awkward during such moments - seemed rather taken aback.

As the giant screens above the stage focused in on a close-up, it became clear that there were tears in her eyes. It's not hard to imagine that this speech - and the way it was received here - may be remembered as one of the defining moments of her career.

The chancellor's speech went down a storm

Angela Merkel key dates

1954: born in Hamburg

1978: earns physics doctorate

1990: joins CDU

1994: becomes minister for environment

2000: becomes CDU leader

2005: becomes chancellor

2013: wins third term

2015: named Time "Person of the Year"

Joerg Forbrig, from the German Marshall Fund of the United States think tank, believes Mrs Merkel designs policy for the long term and that she understands it may take time for the public and her party to understand or agree with her position.

"She takes a very long time to analyse a problem, to understand it. And once she had made up her mind analytically, she determined a position that she was sure was the most promising way of going about this crisis. It seems to me that the public debate in this country is lagging behind her analytically."

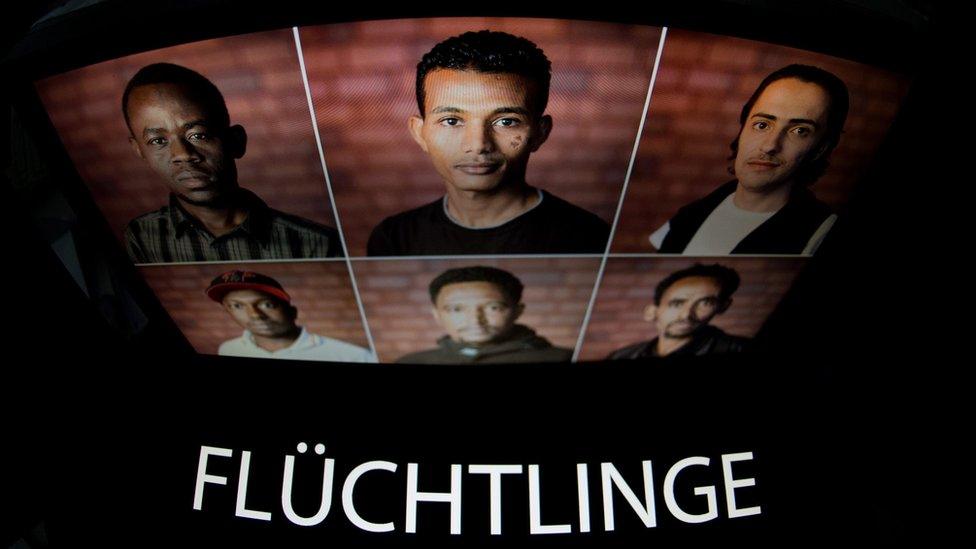

"Fluechtinge" (refugees) was voted Germany's word of the year by the Society for the German Language

Even so, Mrs Merkel's uncompromising stance over refugees has surprised some. This, after all, is the chancellor notorious for caution and apparent indecision. There's even a verb for it here: "Merkeln" (to Merkel), meaning to prevaricate.

Commentators suggest that for Mrs Merkel, the refugee crisis has become a personal crusade, a moral imperative rooted in her upbringing as a pastor's daughter in East Germany.

Inspiring confidence

Others, though, point out that Mrs Merkel's style is changing, that a new more determined leader is taking shape, forged in the fire of successive crises: Ukraine, Greek debt, refugees.

And, according to Peter Mattuschek from the polling agency Forsa, it's a style which, despite a dip in the polls, Germans are coming to like.

"When the euro crisis started, she managed to give people a feeling that she cared about their needs and [was] protecting them from threats coming from abroad. When she said, 'We won't do the rescue package for the banks, we'll do it for you,' this made her strong because people have confidence in her leadership qualities."

And of course - as he and others are quick to point out - there's no-one waiting in the wings to dethrone her as chancellor.

People in Stein still need convincing about Germany's ability to cope with the influx of refugees

Back in Stein, as the brass band finish their last carol with a flourish, people tell me that they worry about how many more people will seek asylum in Germany. What happens next year or the year after that?

Angela Merkel may have persuaded her party that Germany can reduce those numbers, although the means to do so, she says, lie at the European and international level.

Now she must persuade people here.