Migrant crisis: Hungary denies fuelling intolerance in media

- Published

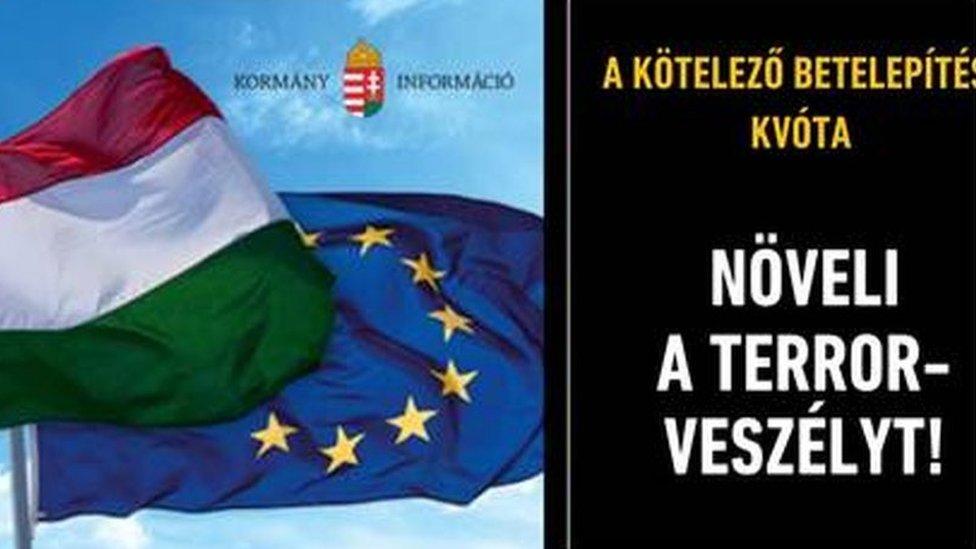

A warning on Hungary's pro-government Magyar Idok website: "The compulsory settlement quota increases the danger of terror"

The Hungarian government has fiercely rebuffed criticism from three top international organisations that its new anti-migrant media campaign is generating fear, intolerance and xenophobia.

"The blindness of those who attack Hungary could lead to the disappearance of European civilisation," Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto said in a statement.

He said the unprecedented joint statement, external by the UN refugee agency (UNHCR), Council of Europe and Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) "is not true - Hungary is depicting reality".

Full-page paid advertisements in printed and online media, and audio and video spots on broadcast media, allege that, among other things:

"an illegal migrant arrives in Europe every 12 seconds"

"the migrants threaten our culture".

The media campaign will last through Christmas until the end of January, and follows similar campaigns this year by Prime Minister Viktor Orban's right-wing government.

In the early summer, a "national consultation on immigration and terrorism" involved sending questionnaires to all Hungarian households.

In July, when the government began building a razor-wire fence along its southern borders, giant posters went up around the country, insisting on the need to "defend the country from the migrants".

'Security threat'

Viktor Orban has led the government's anti-migrant chorus from the start of the year

Few have actually entered Hungary since 16 October, when the fence on the Croatian border was completed, but the propaganda has continued relentlessly.

According to the latest opinion survey by the Median agency at the end of November, the campaign is working: 63% of respondents found migrants "aggressive and demanding" in November, compared with 58% in September.

Meanwhile, 56% believed it was likely or very likely that Muslims would "sooner or later become the majority in Europe, and impose their religion and culture on us".

Dislike of Arabs and "blacks" also grew, while it stagnated towards Jews and gay people.

Mr Orban has led the government's anti-migrant chorus since the start of the year - and watched his Fidesz party's popularity grow in response.

"Mass migration is threatening the security of Europeans, because it brings with it an exponentially increased threat of terrorism," he told a recent Fidesz party congress.

"We know nothing about these people: where they really come from, who they are, what their intentions are, whether they have received any training, whether they have weapons, or whether they are members of any organisation. Furthermore, mass migration also increases crime rates."

Mr Orban's speech writers are careful to stress the phrase "illegal migrants" rather than "refugees". They also avoid or reject any comparison with Hungarians who fled the Soviet army in 1956, after the revolution was crushed, or with Hungarian migrants now in Western Europe, especially the UK.

'Encouraging strength'

Hungary's razor-wire fence on the border with Serbia has been widely criticised

Opposition leftist and liberal parties, already weak, have toned down or forgotten their own, initially pro-migrant rhetoric.

Privately, some senior Fidesz figures do express dismay, even disgust at the tone of the campaign. And in public, several conservative figures have taken a more humane stance.

"The main wave of the current flood of refugees passed us by, but… we were willing to embrace those who knocked on our door," said Varszegi Asztrik, Bishop of Pannonhalma Abbey in western Hungary, interviewed by the HVG weekly.

Some 50 Muslim migrants were given temporary shelter in his monastery.

"At a time when we hear so much about fear," wrote Gergely Prohle, deputy state secretary in the Human Resources Ministry, "about the decadence of European civilisation, about the difficulties of having children, and about the weakness of our faith, there is in this photograph a great and encouraging strength."

The photograph he chose to accompany his article in the Christmas edition of the centre-right weekly Heti Valasz shows an Afghan man holding up his 10-day-old daughter at Roszke, on the Hungarian-Serbian border, shortly before the government closed it on 15 September.

But such sentiments are few and far between in Hungary this Christmas.