Chechnya struggles to stop wave of recruits joining IS

- Published

Officials at Grozny's central mosque are looking carefully for hints of radicalisation

Religious leaders in the southern Russian republic of Chechnya have a new message to preach these days, about the dangers of so-called Islamic State (IS).

They teach that IS has nothing to do with true Islam, labelling it the "devil's army".

But IS is actively recruiting across the North Caucasus.

It is estimated that as many as 500 people have now joined its ranks from Chechnya alone.

'No other path'

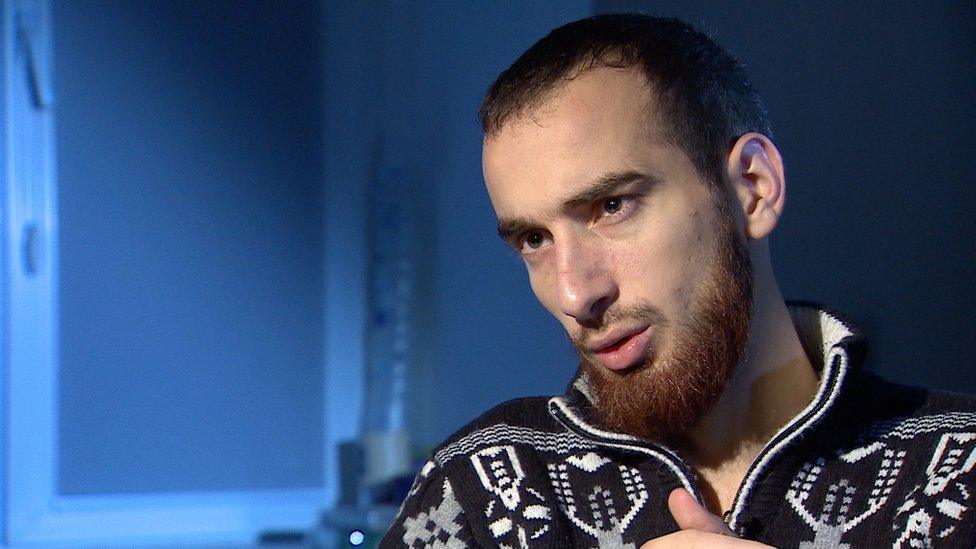

Sayeed Mazhaev fought in Syria with a group that later swore allegiance to IS.

Now back home in the Chechen capital Grozny, he says he was first contacted online by an old friend.

Gradually he and others talked Sayeed into joining them.

"The idea became so appealing that nothing else interested me. It was like I was under hypnosis, my feelings were so strong," he remembers.

Sayeed Mazhaev says he became obsessed with joining what he believed was a holy war

"They persuaded me that going to Syria was the whole meaning of life; that there is no other path than to die for the rise of my religion and for those who are oppressed."

Sent videos of apparent atrocities and urged repeatedly to do his "Muslim duty", 22-year-old Sayeed eventually buckled.

Exodus of extremists

Now free after eight months in a Chechen prison, Sayeed is still wearing an electronic tag.

Fifty-two people have left to fight for IS in Syria from his neighbourhood of Grozny alone.

It is the latest phase in the Islamist insurgency that emerged after Chechnya's brutal war for independence from Russia.

At the local police station, the deputy police chief scrolls through a computer database of those who have gone.

Magomed Magomadov admits that the authorities did not worry too much when the exodus of extremists began a couple of years ago.

"We thought they'd just get killed," he says, so his officers simply noted the names.

CCTV and metal detectors have been installed inside mosques

But as the number has risen, Russia has become concerned that battle-hardened extremists will bring their fight back home.

It was President Vladimir Putin's key justification for launching air strikes in Syria three months ago.

Critics see that as camouflage for a global power game, as Russia props up its ally Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. But efforts to tackle the IS threat at home have also intensified.

Lured to Syria

"Now we tell people that even if they buy a ticket and set off, we can charge them with joining an illegal armed organisation," Magomed Magomadov explains.

"We warn them not to even think of it, because they'll go to prison."

Alleged IS recruiters are paraded on Chechen TV

The vast majority he has encountered were lured to Syria through what he calls a "wrong understanding" of Islam. IS recruiters "mess up their heads", the policeman says.

Those caught can be subjected to public shaming ceremonies. In one recent incident, Chechnya's leader, Ramzan Kadyrov, was shown on television berating a group of men said to have been recruiting for IS.

They stand, heads bowed, then their own relatives are called to join in.

IS recruits in Russia

"Mum, I'm not coming back," Russian TV quoted Varvara Karaulova as saying as she left for Syria

More than 2,900 Russian citizens are suspected of joining IS and other groups in Syria and Iraq, according to the FSB

They include up to 500 Chechens and 643 from Dagestan, according to the heads of those republics

Many are young Muslim men but women have travelled too

One high profile case concerns philosophy student Varvara Karaulova from Moscow, caught trying to enter Syria through Turkey

Now back home with her family, she is being prosecuted after allegedly trying to contact IS members again

More than 150 people have been charged with fighting for extremist groups in Syria, sources say. The minimum prison sentence is 5 years

"It's good they're at least trying to use soft power," acknowledges Grigory Shvedov, of internet news agency Caucasus Knot.

But human rights groups accuse Chechen security forces of abusive methods too, including targeting family members of suspected extremists in a form of collective punishment.

"Chechnya is very well known for being brutal. That's one reason why, in Chechnya specifically, the amount of people happy to join IS is growing," Mr Shvedov adds.

But spotting the warning signs of radicalisation can be difficult.

Lost sons

In the living room of her small, immaculate flat, Lida Bachaeva explains that she thought her sons had gone to Europe to look for work.

Then one day Mansur called from Syria to tell her that his brother, Timur, had been killed. He was 24.

"If I'd known where they were going I'd have grabbed them, told the police, done anything to stop them. But what can I do now?" Lida says.

Lida Bachaeva said she did not see any warning signs of what her sons were planning to do

Like many Chechen mothers she had protected her children through two wars in the republic.

"We thought everything was settled again, then suddenly there was Syria. And now I have lost my sons," she cries.

Battle for minds

Religious leaders have been touring schools and colleges and producing leaflets to convince young Chechens that fighting in Syria is no path to paradise.

"But those who don't accept our message don't say so and we don't have an X-ray to see into their souls," says deputy mufti Usman Osmaev, inside Grozny's vast central mosque.

"IS has good psychologists. They know how to approach young people who feel that no-one has time for them," he adds.

"The young person sees whoever's behind the computer screen as a friend."

Usman Osmaev, the deputy mufti of Grozny central mosque, says countering the pull of IS is proving difficult

Sayeed Mazhaev counts himself lucky to have escaped. He says he realised his mistake after seeing civilians executed in Syria.

He fled when he was injured and sent to Turkey for treatment, and now works with officials urging other Chechens not to be seduced.

"Just because I was lucky enough to get away, others shouldn't think that they can go to Syria - take a look, then come home," Sayeed warns.

"Because they won't be able to. Definitely not now."

It is a battle for minds and Chechnya is once again on the front line.

- Published24 July 2015

- Published28 August 2023