Charlie Hebdo lives on but 'in darkness'

- Published

One year ago this week, Islamist gunmen burst into the offices of the satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo, and killed 11 people, before shooting dead a policeman in the streets outside. Over the next two days, another five people would be killed in co-ordinated attacks, four of them during a siege at a Jewish supermarket in the east of Paris.

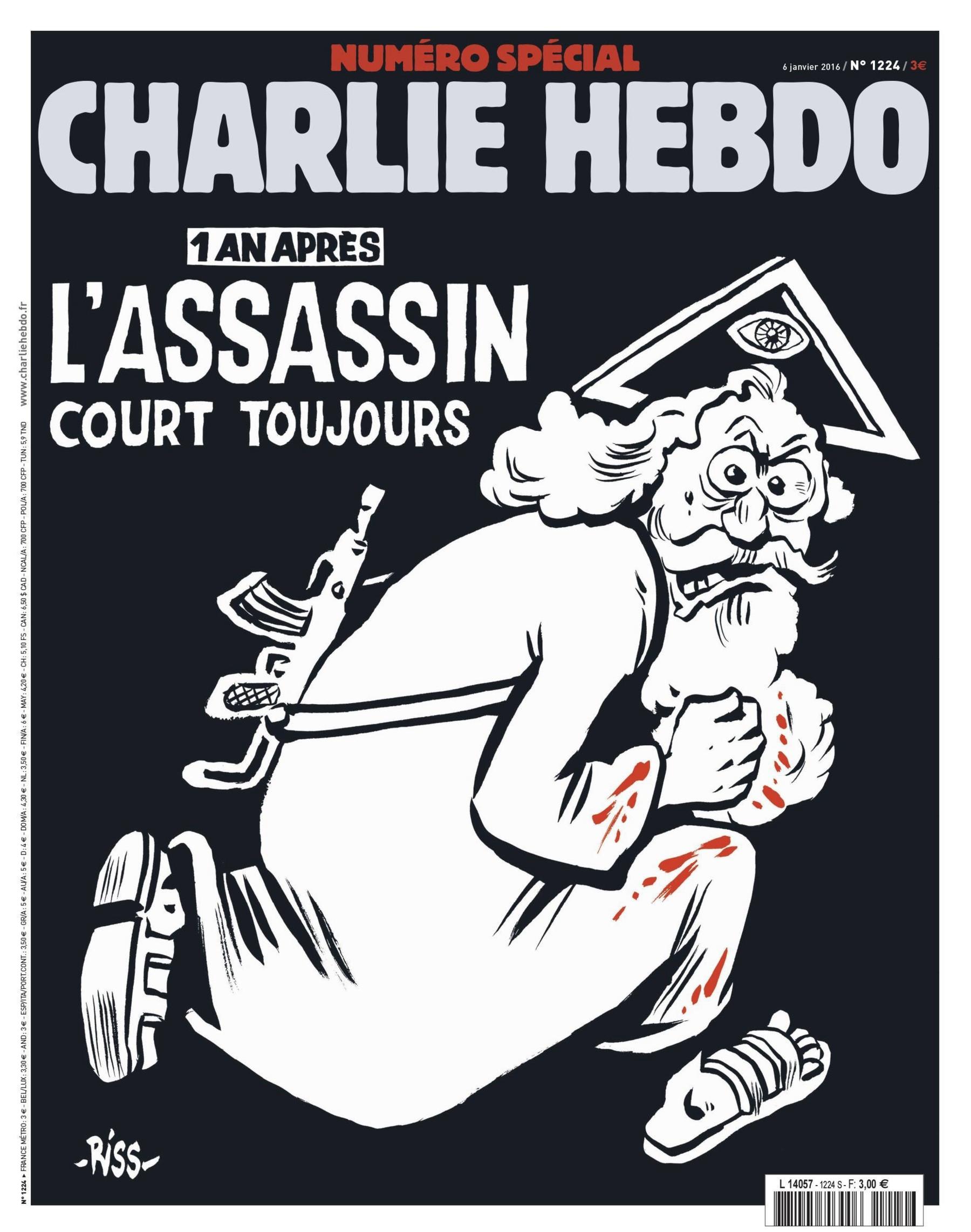

If there's one message the cover of Charlie Hebdo's anniversary edition seems to convey, it's that nothing has changed.

The front cover of this week's Charlie Hebdo

"The killer is still out there" says the caption, while the cartoon shows the bearded figure of God, a Kalashnikov slung across his back, his robes splattered with blood.

The message: Charlie Hebdo is still alive, still printing, still breaking taboos and the main target of its satire is still organised religion.

"I don't think anything changed since 7 January, except the emptiness we are suffering," said the magazine's managing editor, Gerard Biard. "We miss the people, the friends, the talent [but] we try to maintain the same spirit. I think we managed to."

But some things in France have certainly changed. The return to work this week after the Christmas break has been tinged with unease, a dark pall of memory hanging over the start of a new year.

'They live in darkness'

There had been death threats against Charlie Hebdo's team for almost a decade before last year's attacks. That hasn't changed, but the response has - no-one these days laughs them off.

The magazine is still printing, but it's had to move into new offices, with more security. Guards now follow staff members to work, to interviews, and back home again. "They live with their curtains drawn, they live in darkness," one newspaper editor close to the team told me.

Charlie Hebdo attack

And there have been changes inside the magazine too. Chief cartoonists Riss and Luz said last year that they would no longer draw the Prophet Muhammad. Since then, Luz has left, saying it was too difficult to carry on without his murdered colleagues.

Another key contributor, columnist Patrick Pelloux, has also said he will resign, amid squabbles over editorial control and how to handle the vast amount of money that flowed in to the magazine following the attacks.

Managing editor Gerard Biard says the magazine's emergence as an international symbol has brought with it fresh criticism of its provocative and controversial tone, with many people calling for it to have more respect for the views - and beliefs - of others.

People around the world paid their respects to the victims of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, including in Trafalgar Square

But, he says: "What many people call respect is just fear. Trying to find reasons for these bombings, killings, shootings is like trying to count the stars in the universe. Totalitarianism doesn't need a reason to be here. People may understand that, but it doesn't make the fear disappear."

Changing attitudes

The debate over how to deal with that fear was sparked again in the wake of the far bloodier attacks here in November, in which 130 people were killed.

An opinion poll carried out shortly afterwards suggested that more than 90% of the French public were in favour of extending the state of emergency and putting radical suspects under house arrest, and there was a 20-point jump in those who supported air strikes against so-called Islamic State in Syria.

Ten months after the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Paris was targeted again

The two attacks - in January and November - have ensured that security has remained visibly high in France. Some 11,000 soldiers are currently deployed on the country's streets, more than half of them in Paris, and the number of police on duty has shot up by a third to 80,000.

Very quickly after the January attacks, said police union spokesman Stanislas Gaudon, it was clear that the public's attitude towards the police had changed.

"It was heart-warming to hear the crowds cheer police vans during the big demonstration on 11 January. People realised that the police were the last bastion against terrorism. There had been a real breakdown in relations between the police and the French, particularly the young, but I think people are satisfied with us now."

Four days after the January attacks, four million people marched on French streets

On the streets of Paris this week, one resident said he did feel more secure in strategic places like stations. "In France," he said, "it's security before liberty, in England I think it's liberty before security."

"I've just come back from being away for two years," said another, "so it's weird because there's a lot of military and security guards in the shops, but you can't stop living your life."

New terrorism

Some murmur about lessons not learned in the aftermath of Charlie Hebdo, about France's seeming vulnerability in the face of its own radicalised citizens, and those of its neighbours.

Security remains highly visible in France

Xavier Raufer, an expert on terrorism at the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), has warned the French government that the way it tackles the current threat needs to change.

After the gun attacks in Toulouse by Mohamed Merah four years ago, he says, there was no excuse for not anticipating the tragedies that took place last year.

"Since 2012 we have had a totally new form of terrorism," Mr Raufer told me. "Small groups of people - part gangster, part terrorist - who return to Islam, or convert to it, and start planting bombs. But it happens so fast. You have guys committing suicide in the name of Islam without ever having read the Koran. It's a lightning speed process, and that wasn't the case 10 years ago."

The speed with which certain petty criminals can become, in the words of Mr Raufer, "human bombs" is one of the biggest challenges for France, and other European countries.

Security services, he says, are stuck in a mindset where the enemy is an elite target like Osama bin Laden, when in reality the future terrorists are young men and women like the Kouachi brothers (behind the Charlie Hebdo attack) or the Abdeslam brothers (involved in the November attacks), living on the outskirts of European cities.

Cherif Kouachi (L) and his brother Said, the brothers behind the Charlie Hebdo attack, were both born and lived in Paris

'Angry with France'

As France begins the year by remembering the January attacks, a survivor of the siege at the HyperCacher Jewish supermarket told French media about her own recovery, and the cost of living through another, even worse attack on France.

Zarie had been working on the checkout at the supermarket when gunman Amedy Coulibaly came in. Over the course of the next few hours, she watched as some of the hostages were shot dead, before she was rescued by security forces in a blaze of gunfire.

After the November attacks, she said, "It all started again. It was as if I'd been taken hostage a second time. "

Ceremonies to remember the victims of the January 2015 attacks took place on Tuesday

For two weeks, Zarie shut herself away at home, fearing that she would be killed if she ventured out to buy a baguette.

"I'm angry with France," she said. "As if the deaths last January weren't enough, we had to wait for tens of others to die to become aware of the danger of terrorism. I no longer have any trust."

The ripples from the attacks last year have spread out through France, casting their shadow over issues as diverse as migration and regulation of the internet. And they are changing something too in the hidden life of the country - a feeling among many here that this battle with home-grown extremism isn't over, and that France is entering a new kind of era.

"For a year, people had been telling me it was never going to happen again," Zarie says, "but I can no longer believe them."

- Published3 January 2016

- Published14 January 2015

- Published5 January 2016