Can Germany be Europe's Zinedine Zidane?

- Published

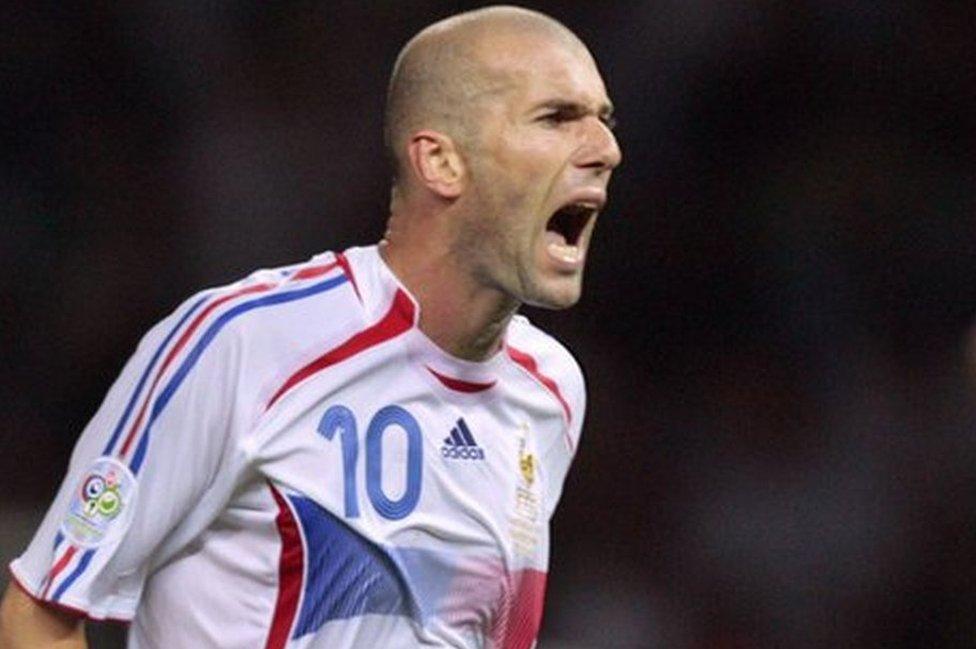

Former French midfielder Zinedine Zidane renowned for his ability to inspire his team

Not long ago, the former Polish Foreign Secretary Radoslaw Sikorski quipped: "I fear German power less than German inaction." And historian and author Timothy Garton-Ash hoped for Germany to turn into the Zinedine Zidane of the EU team: the French midfielder "who not only knits together the whole team's game but also inspires other players by his performance".

In 2015 they got what they, among others, had wished for. The long reluctant Germany left the bench and put on a Europe midfielder's jersey. Subsequently, it held Putin to a draw, scored against Greece in overtime and ended up offside during the refugee crisis.

One of the illusions that 2015 shattered was the idea that Europe was ready to suffer, if not embrace, Germany's role as the continent's "benign hegemon".

The German question

The year's dramatic events, starting with a renewed upsurge in fighting in Ukraine, left the Europeans alienated and the midfielder with the ball, but without a team. Instead of forging a new unity - under pressure and under German leadership - Europe started to come apart.

By the time Angela Merkel was named Person of the Year 2015 by Time magazine, the French were reeling from the terror attacks in Paris, the polls saw a majority of the British in favour of leaving the EU and Poland had a government that would rather bite off its tongue than echo what Sikorski had said.

The unease about Germany's dominance had become so widespread, that the Italian prime minister felt that those concerns needed to be made public. "Europe has to serve all 28 countries, not just one," Matteo Renzi said right before Christmas.

What history had in store for 2015 was the return of the Germany that's always been a stranger in Europe: less state-obsessed than the French, more idealistic than the British, too pro-Russia for the Polish. And too big for all of them.

"Who has appointed the Germans judges of the nations?" John of Salisbury, the 12th Century Bishop of Chartres, demanded to know in 1160 in his opposition to Emperor Frederik I.

Former Polish Foreign Minister Radoslav Sikorski (left) and former German counterpart Guido Westerwelle

Little has changed since then: in 2015 the German Question returned with great vigour - and with it the lesson that the European Union was, after all, not going to serve as the ultimate answer as to what Germany's role in Europe should be. If the idea of the EU was to balance the political and economic powers in Europe, the past year clearly showed that it had failed.

These rifts may not come entirely as a surprise after such bruising political battles as the Euro-crisis. Perhaps they are part of a process that shifts the political weight and which just needs getting used to. It is unlikely though that such a process will eventually lead to great success.

Signs of strain

For one, it dramatically overestimates Germany's strength. A Europe that starts to rely too heavily on Germany is bound to be disappointed. The country is itself at least as ambivalent about its role in Europe as the rest of the Europeans.

Also, it is in many ways weaker than it seems. The meagre contribution to the military fight against Islamic State after the Paris attacks was all the mentally demilitarised country could muster.

With every international crisis that heaped more responsibility on Germany, the more visible the internal rifts became. The Crimean conflict resurrected a substantial anti-Western, pro-Russian sentiment among Germans; the Euro-crisis ended their belief in Helmut Kohl's trusted practice of buying Germany out of any European conflict; the refugee crisis may have been met by an impressive willingness to absorb more than a million refugees - but it came with a strong backlash against it.

In the end, the country's political ground began to shift. The new right-wing party Alternative fuer Deutschland (Alternative for Germany), was founded in the wake of the Euro-crisis and is flourishing on its anti-immigration policies. The success of such a populist party, anathema to the political establishment, is evidence that the country has started to show signs of strain.

Just as playing midfield had cost her on the European pitch, Angela Merkel found herself being assailed at home. As her approval ratings dipped, her political rhetoric climbed. In her party conference address in December Merkel tried to gather support for her stance on the refugee issue by suggesting that "it is part of our country's identity to achieve great things".

Taking in refugees, Merkel seemed to say, had little to do with demographics or humanitarianism, but amounted to a moment of glory in which Germany could prove itself. It was an appeal that rang unfamiliarly grandiose, nationalistic even.

Not much of a team

So, more than anything, the slew of crises and the hard decisions that were part of them, appear to have shaken the country's deeply ingrained faith in its own post-national, European future. By the end of 2015 Germans felt they were doing all the heavy lifting and got very little in return from the rest of Europe.

Italy's prime minister Matteo Renzi, seen here with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, says the EU must serve the interests of all members, not just Germany's

Worse, by refusing to help her out with the refugees, European leaders forced Merkel to appeal to the nation's pride and to swallow her own pride by asking an authoritarian Turkey to help stop the wave of refugees. A Europe in withdrawal mode and a Germany that moved from reluctance to indignation in no time. Not much of a team.

Europe's focus on Germany, it would seem, is misplaced. It fired up a continent-wide blame game and roused German hubris and expanded their sense of order beyond their own territory.

But Angela Merkel can't fix the French economy. They will have to do that themselves. She can't reconcile the British with the rest of Europe. They too will have to do that themselves. She can't drag the Greek tax system into the 21st Century. She can't readjust the European Union, though that's what's so badly needed.

Be careful what you wish for

And Germans remember all too well what happens when one player is forced to lift the game - Zinedine Zidane rammed his head into an opponent. He got sent off and his team lost. But he has moved on from the 2006 World Cup final in Berlin. As Real Madrid's new manager he is no longer forced to lead by example like the German chancellor. Unlike Merkel, he can tell the players what to do.

The Europeans need to solve their problems themselves. Germans might like to think that they have the answers to a great many things. But, as became more obvious as the year went on, they didn't.

If 2015 witnessed a perilously unbalanced Europe, because Germany happened to be the only country unburdened by any serious troubles at home, there is hope for a more level playing field in 2016.

The violent sexual attacks by a group including asylum-seekers in Cologne on New Year's Eve jolted the country's attitude towards the refugee question. What's already clear is that Angela Merkel's Germany won't be much help (or nuisance) to anyone in Europe anytime soon, because now she too has a problem to deal with - struggling with the consequences of opening Germany to so many refugees.

This year, Germany is distracted.

Moritz Schuller is opinion page editor at Tagesspiegel in Berlin.