Cologne attacks' profound impact on Europe

- Published

The events in Cologne and other cities over New Year have left a deep imprint in Germany.

The stories of women running a gauntlet of sexual assault by young men have tapped into society's deepest fears.

In just the city of Cologne, more than 500 cases of violence have been recorded, although not all were sexual attacks.

The consensus in favour of accepting 1.1 million refugees was already fraying. Now the country is deeply uneasy and sharply divided.

"Cologne has changed everything," said Volker Bouffier, external, vice-president of Chancellor Angela Merkel's centre-right CDU party. "People are now doubting."

Women describe 'terrible' assaults

Cologne mayor's 'code of conduct' attacked

What happened during the first hours of 2016 is likely to have a profound impact on the rest of Europe.

Certainly the boldness of the assaults and the sense of a powerless state will haunt the victims, but what has also been lost is trust - the essential glue in any society.

There is now a widely held suspicion that the political elite is not being candid with the German public.

Police were aware of the situation on the streets of Cologne

There was the inexplicably bland initial police report describing the evening in Cologne as a "relaxed atmosphere. Celebrations largely peaceful". It was on social media that news of the assaults first seeped out.

When the Cologne police chief said that many of the young men who had been outside the train station that night had been of North African or Middle Eastern origin, politicians and officials were quick to say they were not drawn from the migrants who in recent months had sought asylum in Germany.

It took the better part of a week to acknowledge that asylum seekers were among the suspects.

The police certainly knew the reality of who had been on the streets. On the night some young men had shown police their asylum documents.

An internal police report describes a man telling the police: "I am Syrian. You have to treat me kindly. Mrs Merkel invited me".

Much not explained

Certainly there is much that remains to be explained. Was this a co-ordinated event and, if so, who was behind it?

The German justice minister believes it was organised, but for what purpose? Or was it just a gathering sparked by social media?

It is also true that large public events like Oktoberfest have been marked by incidents of sexual assault without any migrants being present.

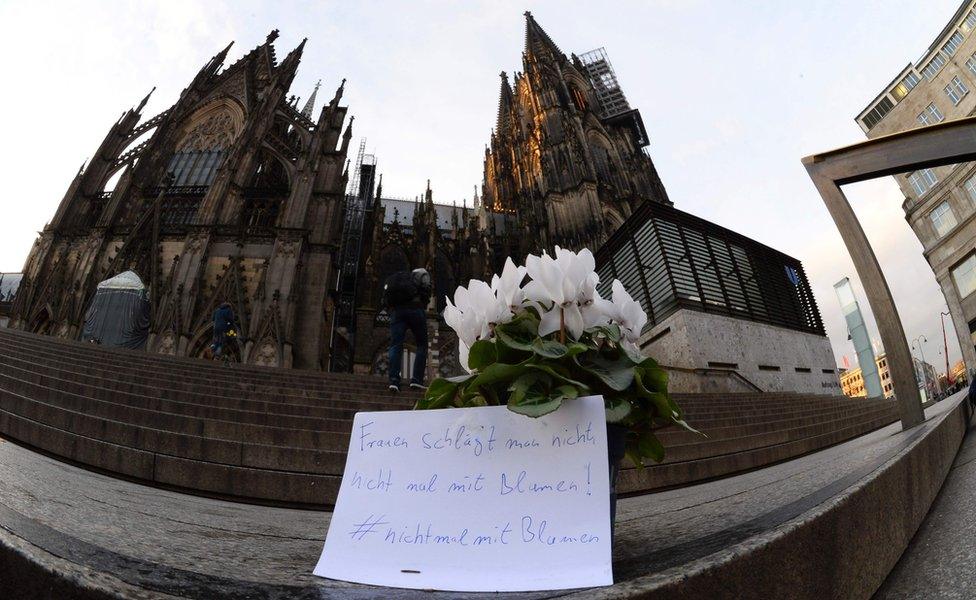

Flowers were laid in protest outside Cologne's cathedral

Although the figures are not up to date, it does not appear so far that the crime rate among asylum seekers is higher than among similar groups in the native population.

What has fuelled the sense of crisis is the suspicion - now widely held - that the German establishment is not telling the truth.

The German public-service broadcaster ZDF did not mention the incidents, external in Cologne in its broadcast until last Tuesday, four days after the attacks.

The broadcaster has now admitted it was a "clear misjudgement" and says that since then, it has been "over-whelmed with hate and anger".

In parts of social media the idea of a "lying press" has taken root.

Supporters of the Pro NRW right-wing party protested after the attacks. The banner reads: "There is no such thing as a right to abuse asylum"

Meanwhile socialist groups demonstrated against Pro NRW: "Don't give an inch to the fascists. Create Nazi-free zones"

Some German papers are quoting police sources saying they are under orders not to report crimes involving refugees.

Many Muslims have spoken out against the assaults, but that has not stopped the main euro-sceptic party Alternativ fuer Deutschland warning against the disintegration of German culture.

In the party's view, Angela Merkel has become a danger and Germany is being asked to compromise its basic values.

The mayor of Cologne suggested it would be wise in future if women "kept men at arm's length".

Echoes from elsewhere

She insists her words were misunderstood. But there have been echoes elsewhere in Europe.

The Viennese police chief Gerhard Pursti said that "women should in general not go into the streets alone in Vienna."

This has caused an outcry, with women complaining that they are being asked to change their behaviour.

Many of them feel torn; they are outraged but they don't want to lend any support to racist groups.

Certainly Angela Merkel was quick to understand that these assaults threatened her whole refugee policy.

Very early on in the crisis she said that "women's feeling of being completely defenceless is intolerable, also to me personally", external. She went on to say that "when crimes are committed, there must be consequences."

The German government is examining changing the law to make it easier to deport, external those convicted of sexual assault but it is unclear how a refugee who has come from Syria could be deported back there.

Pressure building

So pressure will build on Mrs Merkel to limit the numbers of refugees arriving. Already some of her political allies have demanded that.

She has resisted but her political authority has been weakened by these events.

Angela Merkel is under intense pressure at home

In the short term, she has enough political capital to withstand the pressure but she will face further tests in the spring.

There are three state elections and members of her party will watch closely how the CDU fares.

And then, of course, the question is whether the warmer weather will increase the numbers arriving.

Chancellor Merkel's long-stated belief is that migration is not a German problem, but a European one.

It is not seen that way in parts of Eastern and Central Europe.

An EU plan to implement quotas, to relocate refugees across the member states, has failed so far. Only a few hundred refugees have actually been moved.

Turkey has been asked to curb the number of migrants entering Europe

Mrs Merkel has placed a huge bet on Turkey helping to stem the flow of migrants in exchange for financial help and granting people from Turkey visa-free travel in parts of Europe.

This week, senior European officials could not disguise their frustration with Turkey; they have seen little evidence of migrants being turned around at the Turkish border.

Mrs Merkel has said that the passport-free zone, guaranteed by the Schengen agreement, can only work "if there is joint responsibility for protecting the external borders".

It is hard to see how that will happen and, in any event, what is being talked about is an orderly system of registering those who qualify for asylum. It is not about reducing numbers.

New border controls

In the meantime checkpoints, border patrols and fences are springing up in different parts of Europe.

Border controls have been introduced on the Oresund Bridge

Only this week border identity checks were introduced on the Oresund Bridge, external linking Sweden and Denmark.

It is the first time since 1958 that there have been border controls between the two countries.

Denmark has introduced checks on its border with Germany.

Austria is reinforcing its border.

Italy is considering controls on its border with Slovenia.

In the short term, both Brussels and the European establishment portray these measures as temporary.

Certainly Europe's leaders will do all in their power to defend the Schengen guarantee, external of freedom of movement, a key pillar of European integration but the migrant crisis is not receding.

Even in mid-winter, 3,000-4,000 migrants are arriving each day in Germany.

So already in these early days of 2016 the debate about the wisdom of sanctioning large-scale migration in Europe has been re-kindled.

Mrs Merkel herself - in the past - has questioned whether integration is working. Once again there are fears of parallel societies taking root with different cultural rules.

You can sometimes feel that in the banlieues around Paris or in parts of Brussels. But then in parts of London, you see groups of young people hanging out together - regardless of background or creed.

The question for Germany is not just how to protect women without curtailing their lives but how to restore trust with ordinary Germans that they are being told the truth.

It is a question that resonates across Europe. It is hard to think of a series of events so likely to feed the narrative of Europe's anti-establishment and populist parties that an elite is misleading the people.

- Published9 January 2016

- Published9 January 2016

- Published7 January 2016

- Published7 January 2016

- Published8 January 2016

- Published6 January 2016

- Published6 January 2016

- Published5 January 2016