'Jungle' migrants prepare to move - 100 metres away

- Published

Police have given the migrants three days to move away from the road that leads to the port of Calais

This has been a stressful week in the camp they call the Jungle.

Difficult at the best of times for thousands of refugees and other migrants who crowd here, hoping to make it across the Channel from France to England, the camp turns into a mud bath when the winter rain pours down.

To make matters worse, residents and volunteers are now racing against time.

Earlier in the week, the authorities here announced that hundreds of shelters and tents ranged within 100m of a busy motorway would have to move.

This part of the camp has seen frequent clashes with the police, as migrants climb the motorway embankment, block traffic and attempt to board British trucks bound for the port.

It is not quite clear how pushing the Jungle back by 100m will stop any of this, but earlier this week, around 2,000 of the camp's estimated 5,000 residents (the number fluctuates) thought they had until Friday morning to comply.

"I was afraid dramatic things were going to happen," says Mohammed Balla, a well-spoken public health specialist from Sudan's troubled Darfur region, who attended a meeting at which the apparent deadline was set.

The area slated for demolition is a hive of activity

Amid fears of the imminent arrival of bulldozers and riot police armed with batons and CS gas, people started to move. Dozens of mostly British volunteers also arrived to help speed up the process.

It seems to be working but the authorities have pushed back the deadline until Monday.

"They want to reduce the size of the camp," says Philli Boyle, Calais manager for one of the most active volunteer groups, Help Refugees UK.

"We also hear that they want to make a no-man's land between the boundary of the camp and the motorway, for security reasons."

The area slated for demolition is now a hive of activity, as volunteers armed with jeeps and trailers arrive to haul some of the camp's more permanent shelters out of harm's way.

Made of timber and tarpaulin, these are not extravagant dwellings, but in a place of hardship and scant resources, no-one wants to lose them.

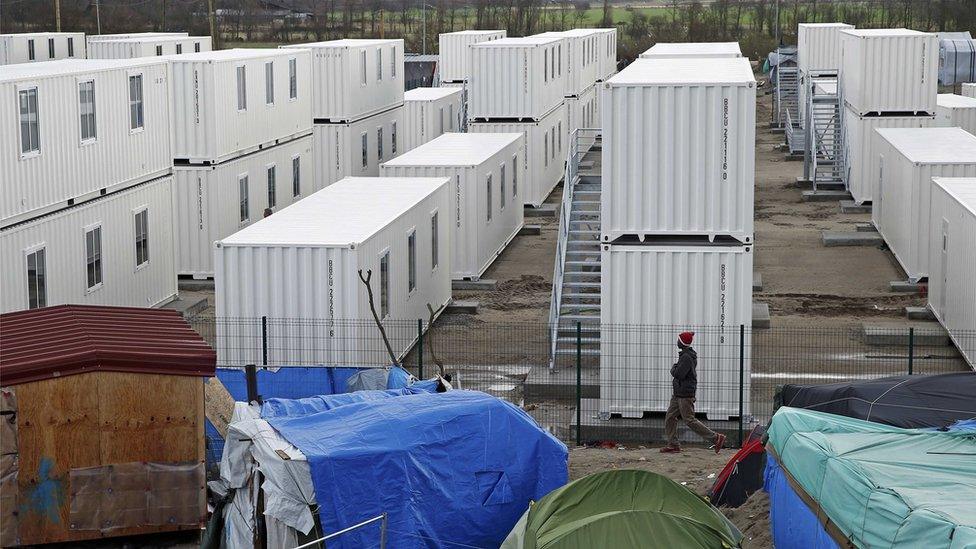

Shipping containers have been installed for the camp's residents

Anything useable - wooden palettes, mattresses and plastic sheeting - is loaded on to the trucks. But the muddy ground is littered with debris, while empty tents shudder and flap in a biting wind and rats scavenge in the filth.

Suspicion

The whole process, inevitably, is causing plenty of anger.

Relations between the local authorities and their unwanted guests have never been exactly cordial. Calais has wrestled with its migrant problem for decades, generally in vain.

Container accommodation at Jungle camp

When the government started to install brand new, gleaming white containers, with heating and enough space to accommodate 1,500 people, many of the Jungle's residents were suspicious.

The compound is fenced off from the rest of the camp, and those who move in will have to use a hand-scanning device to get in and out.

This has led to fears, apparently without justification, it is some kind of internment facility where fingerprints will be taken and migrants forced to register for asylum, robbing them of their chance to make it to the UK.

"They said you are allowed to go in and out at any time at all, but there's a fence," says Adam Mohammed al-Diko, who represents the camp's small Ghanaian community.

"And we don't have any experience of a door where you fingerprint your hand before you go in. We have never heard of this thing."

Those staying in the camp in Calais hope to cross the channel to the UK

Adam blames the camp's large Afghan population for the Jungle's rapid expansion over the past six months, as well as for some of the violence that occasionally erupts between residents and the police.

But the uncertainty with which many view the new containers is typical of this long, difficult history, punctuated by short-term initiatives, forced evictions, occasional clashes and lots of mutual suspicion.

The city has frequently failed to explain its policies, leaving migrants bewildered and nervous.

After all, none of them want to be here anyway.

"We are not here to make fight with police, to harass police or to destroy anything here in Calais," says Mohammed Balla.

"We just came here to stay for a while and continue our journey to the final destination."

Mohammed says he cannot stay in France.

All belongings are precious for the residents

"Life is too short," he says. "How can I learn a new language in one or two years? It needs more than five or six years."

He says he needs to move fast.

"I want to save my life first and then have a normal life, form a family, find work and proceed on."

But for now, the main challenge is moving away from the road, before the bulldozers arrive.

Philli Boyle says she is confident that the camp will be ready by Monday.

"Because we've had a few days to get all the teams on the ground, to make a plan and work with the residents, it's been very smooth," she says.

"Which is the most important thing for everyone."