Detained Turkish reporters defiant over espionage claim

- Published

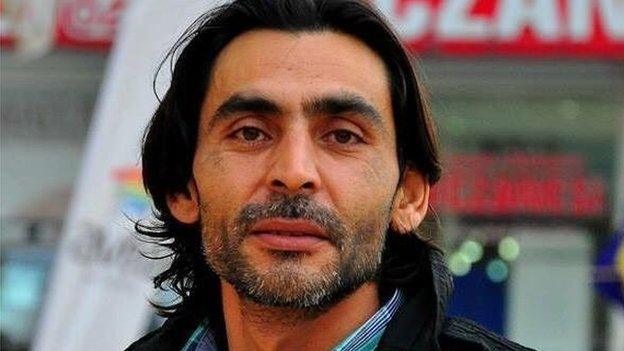

Erdem Gul (left) and Can Dundar have now been kept behind bars for more than 50 days

"We were kept in total isolation for 40 days. We were all alone in our prison cells. This punishment is the same a murderer of five people gets," writes Can Dundar, a prominent Turkish journalist currently behind bars in Istanbul.

Mr Dundar, editor-in-chief of the opposition Cumhuriyet daily has been in pre-trial detention for almost two months now, along with his colleague Erdem Gul, the newspaper's Ankara bureau chief.

In November, a court in Istanbul charged both journalists with espionage after their reports alleged Turkey's intelligence services were sending weapons and ammunition to Islamist rebels fighting the Syrian regime.

Turkish security forces intercepted a convoy of lorries near the Syrian border in January 2014, and Cumhuriyet alleged these vehicles were linked to Turkey's MIT intelligence organisation. Alongside the newspaper report was video footage showing police discovering crates of weapons hidden beneath boxes of medicine.

The government insisted that the lorries were not carrying weapons to the Islamist rebels as alleged, but bringing aid to Syria's Turkmen minority, a Turkic-speaking ethnic group.

Erdogan's pledge

President Erdogan said that "whoever wrote this story will pay a heavy price"

"For the first time in history, a Turkish president personally filed a criminal complaint against a news story not particularly about him," Mr Dundar wrote in a letter to the BBC from Silivri prison where he is held.

"It was [Recep Tayyip] Erdogan's decision to interfere in the civil war in Syria. That's why he saw those uncovering this as his personal nemesis."

Freedom of the press in Turkey

Turkey ranks 149th amongst the 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders' World Press Freedom Index 2015, external

Media organisations in Turkey say that more than 30 journalists are currently behind bars

Most are of Kurdish origin

The government argues journalism in Turkey is among the most free in the world

Mr Dundar and Mr Gul's reports, published in May 2015, triggered a political storm in Turkey as well as a lawsuit filed by President Erdogan.

Mr Erdogan said that the video footage was a state secret, and by publishing it Cumhuriyet daily had engaged in an act of espionage.

"Whoever wrote this story will pay a heavy price for this. I will not let him go unpunished," he vowed live on television.

'Very intimidating'

Mr Dundar's wife Dilek and son Ege have been given limited access to him

Once a month, Mr Dundar and Mr Gul's immediate families are allowed to a "free visit" - when they can actually sit around a table and talk without the impediment of a glass bar.

"It's ironic but we somehow felt relieved when Can was arrested," says Mr Dundar's wife Dilek on the way to Silivri prison.

"Some pro-government columnists were saying he could get killed. Every day when he left home for work, I would look up and down the street to see if there was something wrong. We were relieved that at least he didn't get killed," she says.

"But it is very strange to be allowed to hug your dad only once a month," adds the journalist's 20-year-old son Ege.

"All this is very intimidating. His imprisonment is a threat to all journalists," he adds.

At the gates of the Silivri prison, there are cheers and hugs as they meet Mr Gul's family.

The men's isolation is now over, but the families wonder if the pair will cope in their cramped cell.

"Six steps to one side, eight steps to the other," Mr Dundar explains in his letter.

"It's just the time for good journalism in Turkey now. But we are deprived of practising that right," writes Mr Gul.

EU criticism

Silivri prison, just west of Istanbul, is believed to be Europe's largest penal facility

Neither man knows what he is accused of, as no indictment has been laid.

"(The government) cannot say that we have actually been imprisoned because of our journalism. They are trying to deceive the public and the world by saying that we have in fact committed other crimes," writes Mr Gul.

And Can Dundar is critical of the European Union too, for agreeing to provide Turkey with €3bn (£2.3bn; $3.3bn) to stem the influx of migrants and refugees.

"It is very disheartening for the West to turn a blind eye to the growing authoritarianism in Turkey in exchange for establishing a detention camp for refugees," he writes.

No regrets

Mr Dundar says he has no regrets over publishing the story that caused his imprisonment.

"I am a journalist. My job is not to defend the interests of the state, but to defend the truth, the interests of the people and the public.

"Iran-Contra, Watergate... these are all examples of news stories when the state was caught red-handed. In all these cases, the people who committed the crimes paid a price, not the ones who uncovered them."

He believes that will also happen in Turkey, sooner or later.

- Published26 November 2015

- Published14 December 2014

- Published13 August 2013

- Published28 December 2015