Who were Germany's Red Army Faction militants?

- Published

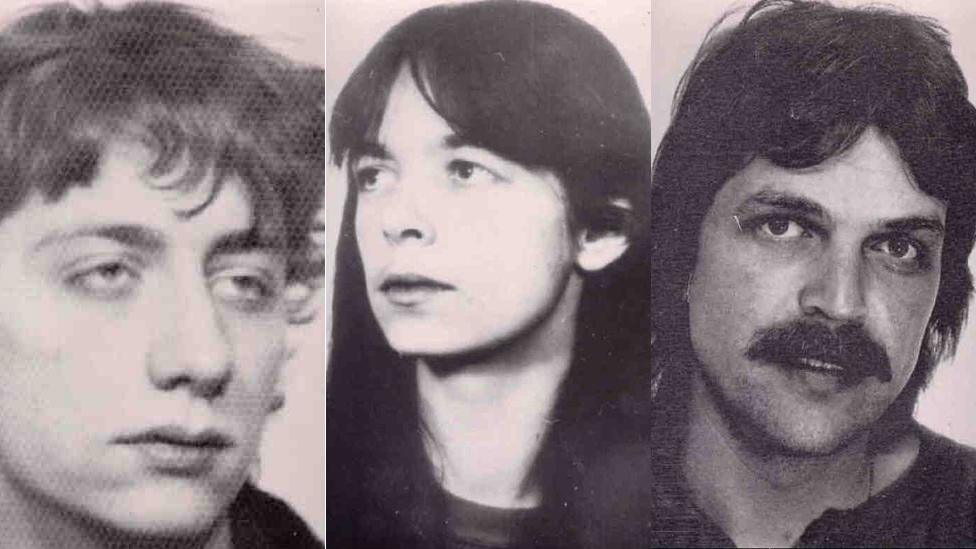

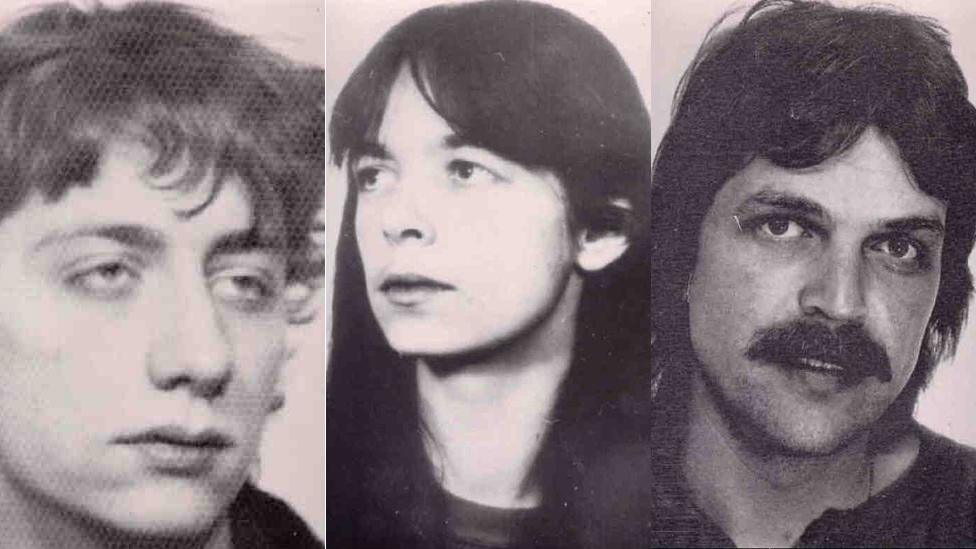

German officials say wanted RAF militants - (left to right) Burkhard Garweg, Daniela Klette and Ernst-Volker Staub - were behind last year's attack

German officials have confirmed that a botched armed robbery near Bremen last year was the work of three wanted militants from the now disbanded Red Army Faction (RAF). However, prosecutors say "there is no evidence to suggest a terrorist background" - and instead "it must be presumed the crime aimed to help finance... underground lives" of the fugitives.

The BBC News website looks at the long terror campaign by Germany's most notorious far-left guerrilla group, also known as the Baader-Meinhof gang, whose members killed more than 30 people in the 1970s and 80s.

On 5 September 1977, a woman with a pushchair stepped out in front of a car on a street in Cologne.

The driver, who was chauffeuring one of West Germany's most powerful industrialists, was forced to brake.

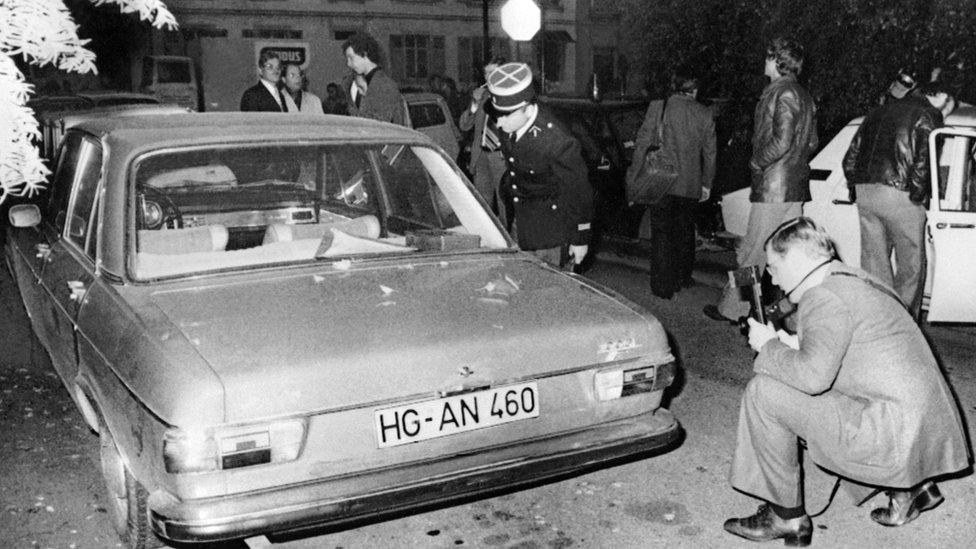

The woman pulled out two machine guns, and her accomplices, following behind, bundled Hanns Martin Schleyer out of the car. His bodyguards were killed at the scene and one month later, his body was found in the boot of a car.

RAF militants murdered German industrial leader Hans Martin Schleyer in 1977 and dumped his body in an Audi car

Schleyer is one name on a list of the victims of the RAF during a campaign against members of the German elite and US military personnel which started in the late 1960s.

Born from the radical student movement of that period, the RAF comprised mainly middle-class youngsters who saw themselves as fighting a West German capitalist establishment which they apparently believed was little more than a reincarnation of the Third Reich.

At the height of its popularity, around a quarter of young West Germans expressed some sympathy for the group. Many condemned their tactics but understood their disgust with the new order, particularly one where former Nazis enjoyed prominent roles.

Their critics meanwhile denounced them as murderous nihilists - desperate for a cause but with no real political goals.

Library plot

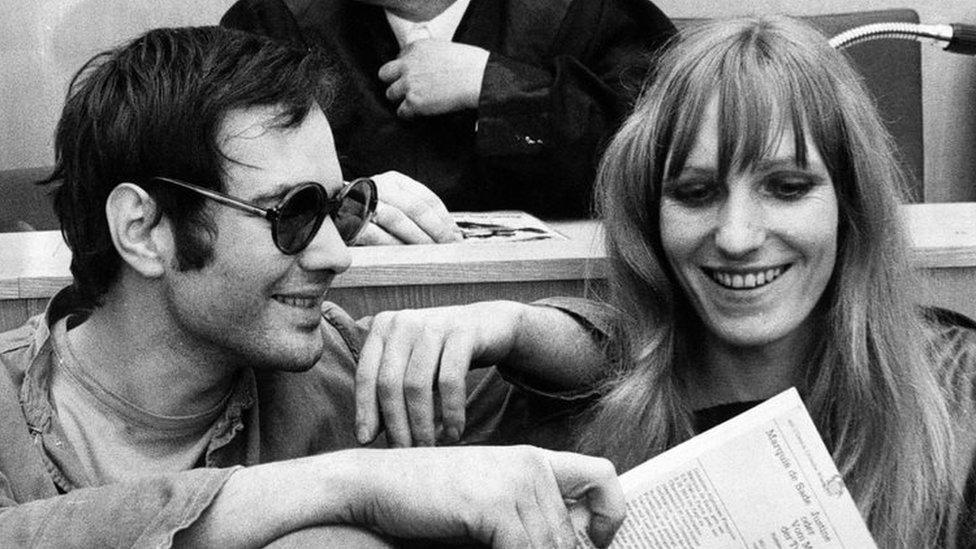

Andreas Baader - seen here with Gudrun Ensslin - was imprisoned after a trial in 1968 but then managed to escape

...only to be re-arrested during a shootout in Frankfurt in 1972

It was the 1967 killing by police of a young activist during a demonstration in Berlin against a visit by the Shah of Iran that apparently persuaded Andreas Baader that the post-war authorities were little better than that which they had replaced.

Vowing to mount a violent campaign, he started off in 1968 by detonating home-made bombs in two Frankfurt department stores.

Arrested and imprisoned, he escaped in 1970 during a library visit with the help of a left-wing campaigning journalist - Ulrike Meinhof - and the Baader-Meinhof gang was firmly established in the public mind.

In 1970, several members of the group headed off to Jordan where they were taught how to use a Kalashnikov at a camp run by the Palestinian Liberation Organisation.

They spent the next two years robbing banks and bombing buildings back in Germany.

Baader was then captured with accomplices Jan-Carl Raspe and Holger Meins in a Frankfurt shootout on 1 June 1972.

Baader's girlfriend Gudrun Ensslin was arrested a week later, and Meinhof was caught in mid-June.

'German Autumn'

Two of the hostages were shot dead during a long siege of the West German embassy in Stockholm in 1975

A second generation of militants then took up the fight, carrying out some of the bloodiest and most high-profile attacks in order to secure the release of their heroes, whose trial - the longest and most expensive in West German history - opened in 1975.

That same year the West German embassy in Sweden was seized; two of the hostages, both attaches, were shot dead during the 11-hour siege after Chancellor Helmut Schmidt refused to give in to demands that all the suspects be released.

1977: Campaign escalates

7 April: Chief public prosecutor killed

30 July: Head of Dresdner Bank killed

5 Sep: Hanns Martin Schleyer abducted and later killed

13 Oct: Plane hijacked

18 Oct: Baader, Ensslin and Raspe commit suicide

In the course of the trial, Meinhof was found hanging from a rope made of towels in her cell - her death sparking a stream of conspiracy theories from her followers.

The trial concluded a year later, with the three remaining defendants sentenced to life imprisonment for murder and attempted murder.

A new series of assassinations had already begun.

On 7 April 1977, chief public prosecutor Siegfried Buback was killed in Karlsruhe by a motorcycle hit squad.

Three months later, the chief executive of Dresdner Bank, Juergen Ponto, was killed at his home in Frankfurt.

But it was the September abduction of Schleyer, head of the German Association of Employers and a former member of the Nazi party, which kicked off a series of events known as the "German Autumn".

Hijack mission

The RAF announced its dissolution in a letter with the group's logo in 1998

Schleyer's captors offered his release in exchange for Baader, Ensslin and nine others.

But even as the negotiations were being carried out, Arab sympathisers were finalising a plan to hijack a plane full of German tourists bound to Frankfurt from Majorca to increase the pressure on the authorities.

The aircraft, seized on 13 October, went first to Italy, then Cyprus, Bahrain and Dubai, before finally landing in Mogadishu, where the captain was shot dead by the hijackers.

Shortly afterwards, German elite commandos stormed the plane, killing three of the hijackers and freeing the hostages.

The success of the mission provided a ray of hope for a country where many felt under siege. But it was the final blow for the group's leaders in prison.

As news broke, Baader, Ensslin and Raspe committed suicide - although there is still some controversy as to how they obtained the weapons they used.

The next day, Schleyer's kidnappers announced he had been killed.

Communist help

Whether there was any great ideological design behind the killings of the 1970s is unclear. By 1977, it looked as though the release of the imprisoned had become an end in itself.

Some analysts believe the RAF had hoped to push the state to breaking point, goading it into introducing a series of illiberal measures that would whip up anger within the left and spark some form of civil war.

Indeed comparisons have been drawn with the crackdown on some civil liberties which followed the 9/11 attacks on the US and the steps taken in Germany during that period, when new laws were quickly introduced to limit suspects' rights and bolster police powers.

But while it initially enjoyed some sympathy from the left, the RAF found itself increasingly isolated as the years went by, although it did find assistance from communist East Germany, where a number of their members were given refuge.

Attacks continued throughout the 1980s, but the group never achieved the kind of prominence it had enjoyed in the 1970s.

Arms industry executive Ernst Zimmermann was killed in 1985, the same year a bombing at a US airbase killed two people, and in 1986, Siemens executive Karl-Heinz Beckurts was killed.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 weakened the group immensely. After a long lull, on 20 April 1998, the group announced its dissolution.

"The revolution says: I was, I am, I will be again," it declared as it signed off.

- Published19 January 2016

- Published30 September 2010