Migrant crisis: How Lampedusa memorial reached British Museum

- Published

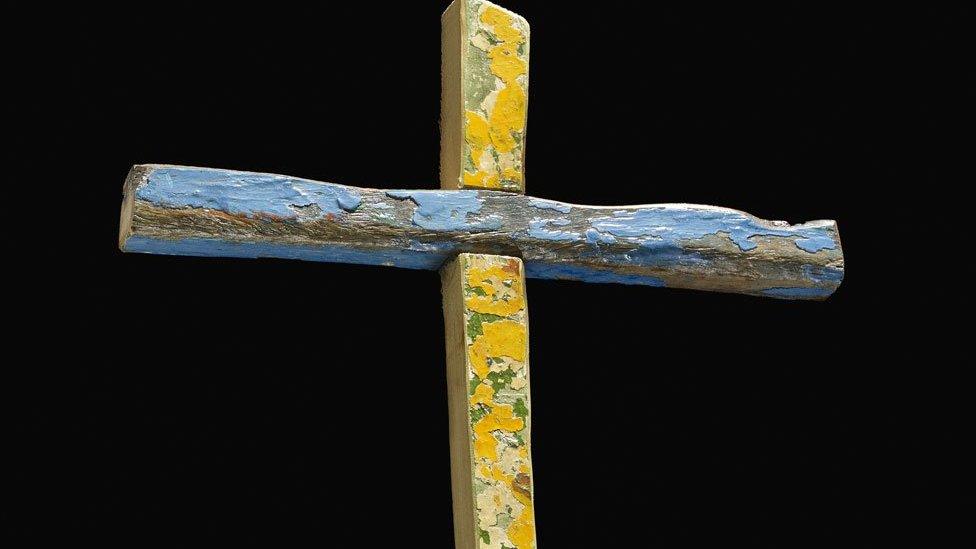

Francesco Tuccio made his crosses from wreckage of migrant boats arriving on Lampedusa's shores

One Sunday in 2011, at the height of the Arab spring, a carpenter from the Sicilian island of Lampedusa made a decision to stop making furniture.

Francesco Tuccio was at Mass in his local church and among the congregation were bedraggled groups of newly arrived Eritrean migrants, weeping for loved ones who had drowned during the Mediterranean crossing.

After the service Lampedusa's carpenter went to the beach and began collecting the blistered, brightly coloured driftwood from the wreckage of migrant boats that had washed up on Lampedusa's shores.

Alone in his workshop, Francesco carved crosses from the timber, shivering at the wood's strange touch which he said made him think of holy relics and which smelt "of salt, sea and suffering".

He asked his parish priest to display a big, rough cross above the altar to remind the congregation of the migrants' desperate plight and he offered every migrant he saw a small cross as a symbol of their rescue and of hope for a new life.

Lampedusa and the migrant crisis

October 2013: 366 migrants died when their boat capsized off the island

April 2015: 800 people are feared to have drowned when a boat sank in Libyan waters off Lampedusa

Lampedusa is Italy's most southerly point, closer to Africa than Europe

Migrant arrivals by sea in Italy last year reached 153,842, down from 170,000 in 2014

856,723 migrants arrived by sea in Greece in 2015

Europe's migrant crisis: Special report

The carpenter and the museum BBC Radio Four PM report

Maps and graphics: Migration to Europe charted in detail

British Museum boss's final acquisition

British Museum, external: The Lampedusa cross

Within a few weeks, the carpenter had commissions for migrant crosses from every parish in Sicily. And within a couple of years he was making Pope Francis an altar and chalice from the driftwood.

I told that story on BBC Radio 4's PM programme last May. Listening at home in London, British Museum senior curator Jill Cook was mesmerised by Francesco's tale.

On a personal level she was deeply moved by the carpenter's kindness, and professionally, too, she was extremely excited.

Here, she thought, was an object she could acquire for the museum and which would put the migrants and their story firmly into the museum's record.

"We don't show photographs at the museum," Jill explained to me "We only show objects, and so the migrants, who have nothing, were always going to be invisible. And then I heard about the carpenter and his crosses."

Jill Cook felt so strongly that the museum should have a cross that she dared not tell her bosses what she was doing in case they stopped her.

Instead, she swore an Italian colleague to secrecy and asked him to call Mr Tuccio and commission him to make her a cross.

Wrecked migrant boats lie abandoned on a beach on the island

Lampedusa's carpenter immediately agreed to make a cross and donate it to the British Museum. The curator began to contact archaeologists she knew to sort out the complicated logistics of bringing it to London.

She needn't have bothered. Francesco Tuccio popped it in the post and one morning his parcel arrived on her desk.

There were tears as Jill Cook defiantly unwrapped her cross in front of the museum's director and other senior staff.

She remembers a great silence before she stuttered something about it being living history and deserving a place in Britain's greatest collection of historical artefacts.

More silence followed until the museum's then head, Neil MacGregor, announced that not only would he accept the cross into his collection but that he would select it as the last acquisition of his directorship.

The Lampedusa cross now takes pride of place in the British Museum

And so a crude, wooden cross with blistered blue, green and yellow paint now stands in a large glass exhibition case at the British museum, a testimony to history in the making.

Francesco Tuccio chose the wood he'd used carefully - it came from a boat which capsized off the coast of Lampedusa on 3 October 2013 with the loss of 366 lives.

This was the disaster that prompted the Italian navy to launch their Mare Nostrum sea and rescue mission.

"I was so happy and proud when the museum contacted me. And then I asked myself a question," he said.

"If this message has reached such an important museum, visited by people from all over the world, is this enough to break down the wall in the hearts of people still indifferent to this terrible crisis?"

It is hard to stand in front of that humble cross, in the middle of so many opulent and priceless exhibits and not to be moved to tears. Its message is powerful, direct and so deeply sad.

For Jill Cook it is an object upon which hang so many stories. A testimony to an extraordinary period of history, but also she hopes, a testimony to humanity.

- Published18 December 2015