Brexit worries on both sides of the Irish border

- Published

Brexit debate held in Newry last autumn

There is little sign of the scars of the past in Newry these days - the Georgian High Street looks prosperous, and the modern shopping centre which has been developed along the quayside of the town's 18th Century canal is buzzing with life.

But the small group of public officials and local activists I met in a cafe there all remember when this area saw the Troubles at their most savage.

And they associate the changes that have come, thanks to the peace process, with the benefits that have flowed from EU membership.

Newry is just north of Northern Ireland's border, and Conor Patterson, now chief executive of the Newry and Morne Enterprise Agency, recalled what it was like to cross it in the bad old days.

"My mother was from Dundalk (in the Republic), so we travelled every week from Newry to Dundalk, and experienced weekly what the hard border meant in practice," he says.

"That was long queues - not just through the security border but thereafter at the customs post… it was really tough."

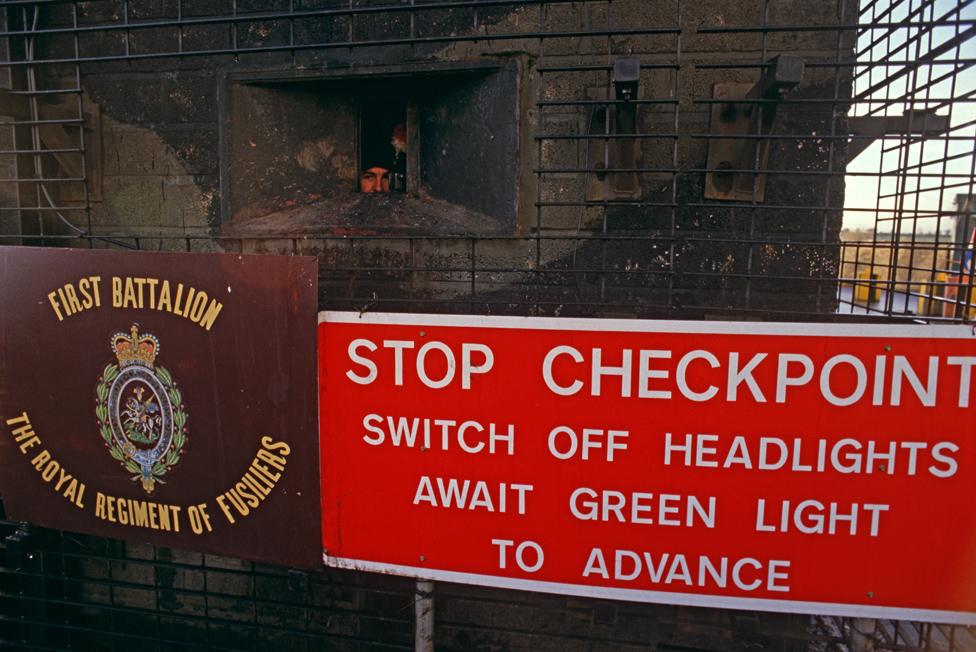

Border crossing point during the Troubles

Pamela Arthurs, chief executive of East Border Region, a local authority-led cross-border organisation, worries about a Brexit threat to the stability which, she says, has been brought to the region by £2.4bn of EU funding.

"The concern we would have is if there was a Brexit, what would the alternative be?" she asks.

"Are we assured that the amount of money would continue?"

Find out more

Listen to Brexit: The Irish Question by Ed Stourton on BBC Radio 4's Analysis programme on Monday 8 February at 20:30 GMT, or catch up via the iPlayer

The UK's EU referendum: Everything you need to know

Unionists who want to leave the EU bridle at the idea that it would undermine the peace process.

"We have come through far, far more difficult challenges to the political institutions in the peace process than this issue," says Nigel Dodds, MP for Belfast North and deputy leader of the DUP.

"The peace process was based on a desire to move Northern Ireland forward, away from years and decades of violence. That's not going to be interrupted or disadvantaged by whatever decision we make on the EU membership issue."

But the way the peace process has been raised as an issue in Northern Ireland reflects an important dimension to the forthcoming referendum on Britain's membership of the European Union.

The Brexit debate can look very different from different parts of the United Kingdom.

Since the last time we voted on Europe - in 1975 - there has been a constitutional revolution.

The devolution of power to the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh and Northern Ireland Assemblies has changed the relationship between the constituent parts of the UK profoundly.

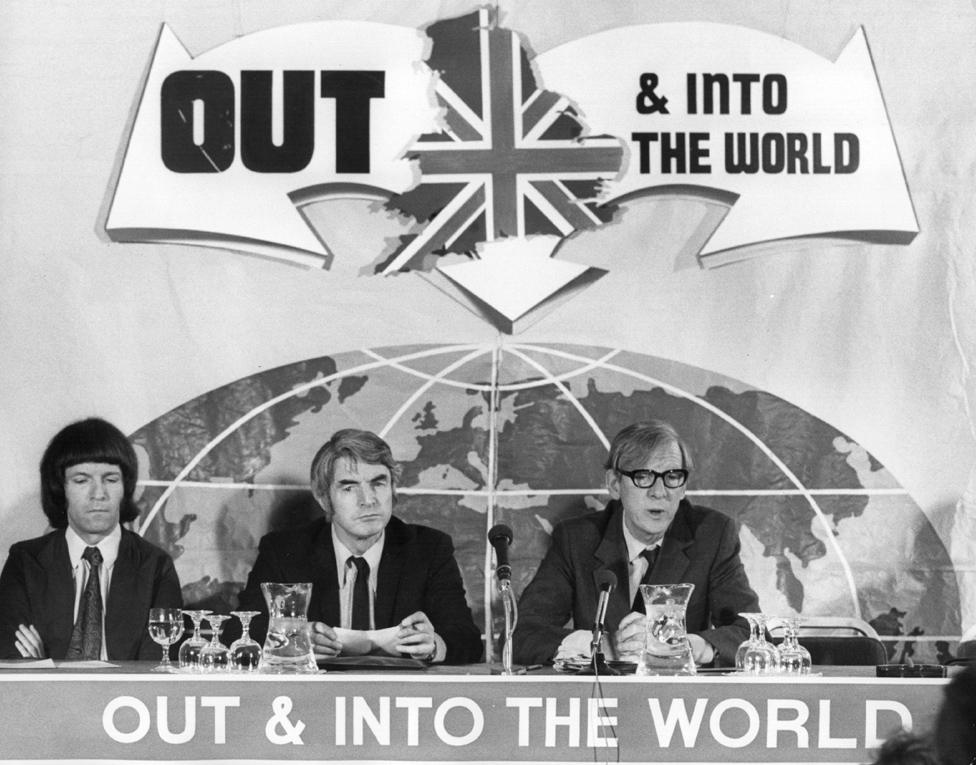

Anti-European campaign for a 'No' vote in the referendum on the EEC

Dr Jo Hunt of Cardiff University, who studies the impact of devolution on the way government works in the UK, says that the "devolved parts of the UK have developed their own relations with the European Union", and argues that that is likely to be reflected in the way people vote.

In Northern Ireland the most important factor which makes the Brexit debate different is the border.

It is the UK's only land border with another sovereign state, which runs for more than 300 miles (483km) from Carlingford Lough on the Irish Sea to Lough Foyle in the North West.

And fears that it might become a so-called "hard" border have prompted Dublin to get involved in the the UK's internal debate in a way some Unionists resent.

"When you have two countries that are linked in the way our countries are, with a land border between us and extraordinary economic, political, historical people-to-people links, anything that puts a barrier between them has to be a negative thing from our point of view," says Dan Mulhall, the Irish ambassador in London.

His Prime Minister, Enda Kenny, went a step further and, on a recent trip to London, warned that a Brexit could cause "serious difficulties" for Northern Ireland.

Enda Kenny (right) has expressed concern over a possible Brexit

"I don't dispute that Irish Republic leaders and politicians have a right to express a view as far as it affects the Irish Republic," says the DUP's Nigel Dodds.

"I am critical when Enda Kenny comes to the UK and says a decision to leave is bad for Northern Ireland."

And "leave" campaigners challenge the assumption that the border would change radically.

Veteran MP Kate Hoey who was born in Northern Ireland and is co-chair of Labour Leave says: "I don't see a situation where we would end up with big barriers up."

"I see no reason if we were not in the European Union why we wouldn't build a good relationship with the Republic that would work out a lot of these issues".

Sinn Fein has in the past been sceptical about some aspects of the EU, but they will be in the "stay" camp, and it sees the possibility of what Martina Anderson - one of the party's MEPs - calls a "constitutional opportunity".

If the leave campaign wins but Northern Ireland votes to stay, it will, like the SNP in Scotland, push for a second, separate referendum there.

"The days of Mother England wagging its finger to Scotland, Wales and to us in the North, and that we would be pulled out of the EU if the people of Northern Ireland are against that, are over," Anderson says.

Many of these positions, of course, reflect local political concerns, but their impact could be felt right across the UK.

Cardiff University's Dr Jo Hunt argues that the referendum "is far more than just a question about remaining in the EU. It is about our constitutional future".

Devolution has, she points out, been "an ongoing and evolving" process.

"This," she believes, "could be seen as a trigger button."