Desperation fuels Europe's zeal for migration deal

- Published

There is desperation on all sides of Europe's migration crisis - desperate migrants are posing a problem which European politicians are desperate to solve

"Where there's a will, there's a way," Angela Merkel has insisted since the migration crisis exploded across Europe last year.

For months she's resisted closing her country's borders and setting an upper limit on the number of asylum seekers allowed into Germany despite rising, and at times frantic, public and political pressure to do so, including from within her own CDU party.

Iron Angie - as she's sometimes known at home - demonstrated her unwavering determination once again at yesterday's EU-Turkey summit and in the lead-up to it.

There have been dark mutterings in the German media that, despite increasing problems at home linked to the arrival of over a million asylum-seekers, the German chancellor has spent more time in Ankara than Aachen, Berlin or Cologne of late.

But there was stubborn purpose behind the shuttling.

Mrs Merkel's political future - and her legacy, after a decade as German chancellor - are hanging in the balance.

Big and bold

She faces three key regional elections this weekend, with polls predicting huge gains for the anti-immigrant AfD party.

She needed something big and bold on migration, allowing her to avoid performing an awkward U-turn on her national policies but at the same time sending a clear message to the people of Germany that she has the situation in hand.

Iron Angie has resisted pressure to dilute her liberal approach to migration - but knows her future hangs in the balance

Make no mistake - it was Germany and no other European nation that insisted on a summit with Turkey this week.

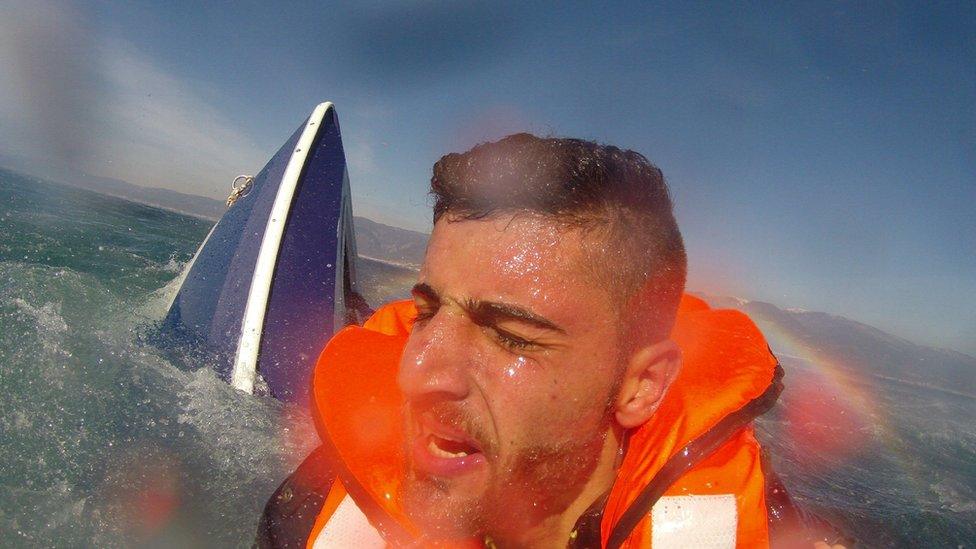

Turkey is key to resolving Europe's current migration chaos. That's where most refugees and others jump on board people smugglers' dinghies, risking their lives to enter Europe via the Greek islands.

But trust between Turkey and the EU is not strong. An "action plan on migration" between the two back in November failed to yield many results.

There has been little sign of Turkey cracking down on people-smugglers along its coastline, and limited evidence of the €3bn (£2.3bn; $3.3bn) the EU then promised Turkey in humanitarian aid.

So Mrs Merkel began a new push for what she hoped would be a better Turkish deal.

Donald Tusk, the head of the European Council, which represents all EU member countries in Brussels, joined in the efforts (after all, he would be the summit host), flying to Turkey ahead of Monday's meeting.

But neither of these seasoned politicians were quite prepared for what is now being described as a "Turkish bazaar" here in Brussels.

Turkey's Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu arrived at the summit all smiles for the cameras.

"Turkey is ready to work with the European Union," he beamed - omitting to say at what price.

Then, behind closed doors, he slammed the EU with a whole host of additional political and funding demands:

More money - at least another 3bn euros to help with the more than 2.5 million refugees already in Turkey

The resettlement of one Syrian from Turkey to the EU for every Syrian readmitted by Turkey from Greece (the EU now hopes to send all migrants arriving on the Greek islands, including Syrians, back to Turkey)

Faster access to visa-free travel in most of the EU for Turkish citizens

The re-opening of stalled talks on Turkey's bid for EU membership

Even a few months ago, my bet is that faced with this steep list of demands, EU countries would simply have turned their back and walked out.

Not now.

Chancellor Merkel isn't the only one desperate to solve the migrant crisis: The EU's credibility is crumbling, its members have never looked less unified and Greece, stuck with tens of thousands of stalled migrants on top of being saddled with crippling euro debt repayments, threatens to implode.

The bottom line, for the EU, is to put off anybody and everybody from getting in dinghies or trying any means possible to get to Europe to improve their lives. It hopes to send every economic migrant back home and to pay to look after refugees in camps closer to theirs.

Turkey, which borders Iraq and Syria, is on the frontline of the crisis - and Europe hopes may hold the key to tackling it

Voters across Europe say they are spooked by the migrant crisis. But however much Europe's leaders and EU bosses in Brussels fear for their future, they can't compromise all their principles trying to make this problem "go away".

And that is why last night's summit didn't end in a deal. Of course, triumphant words flew out of the mouths of leaders and broadcasters across Europe - "turning point", "Big Bang" and "breakthrough".

Step too far?

But that is only if - and it's a big if - the proposals are written up and signed at another migrant summit next week - and "if" they are then implemented.

There's a lot to think about.

Can the EU afford to close its eyes to the Turkish president's increasingly autocratic and arguably anti-democratic behaviour in its rush to do a migration deal?

Just before the summit, the Turkish government took over one of the country's best-selling newspapers and tear-gassed outraged protesters on the streets of Ankara, for example.

And what of the legal implications of the EU exporting migrants en masse back to Turkey?

The UN has warned this could go against international humanitarian law, with some asylum cases needing to be heard here in Europe, they say. Turkey does not have asylum laws in place for Afghans and Iraqis for example, so what will happen to those migrants?

And then there are the logistical challenges.

Imagine the scenes - not just young men, but old women, wheelchair users, pregnant mothers and screaming babies, many from Syria and other troubled areas. After all they've been through to to get to Greece, will they meekly accept getting on a boat or plane to be sent back to Turkey?

And these are just some of the complications surrounding an EU-Turkey deal, never mind the splits in Europe over how to deal with the migrant crisis.

So, on Monday Angela Merkel got what she needed for her weekend elections: a tough-sounding something with the promise of a Turkey deal in the offing.

Conveniently for her, the votes will be counted in Germany before the talk from the summit begins to publicly unravel.