Ireland election: What went wrong for PM Enda Kenny?

- Published

Enda Kenny's resignation late on Thursday night as taoiseach (prime minister) means the start of a period of intense horse-trading - new terrain for Ireland, with the outcome very unclear.

There was no photo opportunity as Mr Kenny handed his resignation to President Michael D Higgins. The late-night drive to his Phoenix Park residence was a muted affair compared to his installation as leader after a landslide election win in 2011.

The country was then in the grip of economic disaster, after the €85bn (£71bn; $94bn) bailout ordered by the EU, European Central Bank and IMF "Troika" following a disastrous banking crash in 2008.

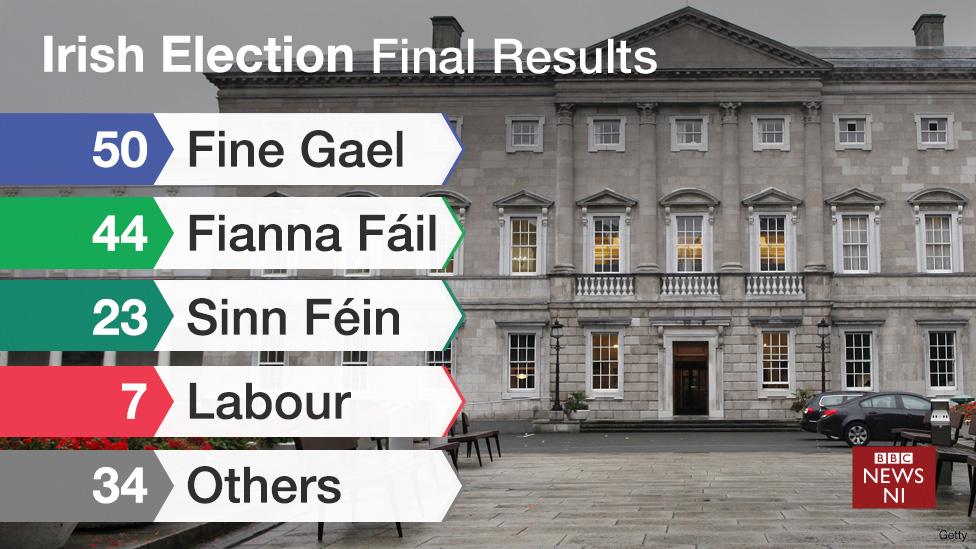

On 26 February Irish voters rejected the outgoing Fine Gael-Labour coalition government led by Mr Kenny, but left no winner in a position to take over.

For Mr Kenny, electoral defeat is a bitter personal disappointment - quitting on a day when it was revealed Ireland's economy had grown by 7.8% in 2015, growth not seen since 2000 and the heyday of the "Celtic Tiger" boom.

But the portrayal of Ireland as an austerity success story under Mr Kenny is key to understanding his defeat.

Election promises in 2011 to refuse to sink any more state money into failed banks were replaced with acquiescence once in power to the Troika's demands - and acting as its zealous agent in pursuing a painful course of punishing austerity.

Ireland was broke and had debts to pay - but anger that the bill included the gargantuan debts of banks and property developers ran deep among many people struggling to make ends meet during the recession.

Cuts to public services intensified this anger, hitting Mr Kenny's party and his coalition partners hard at the polls.

Charges for water - once paid for from central taxes - created Ireland's biggest mass movement of modern times.

The impact of spending cuts on the vulnerable struck a raw nerve in a society where compassion for the weak remains a strong political force.

Thousands marched in Dublin ahead of the election to protest at water charges and austerity

The Right2Change movement brought together those angry at inequality in Irish society

The day Mr Kenny quit, the town of Longford came to a halt with a protest over the loss of two special needs school assistants. The government may be gone but its austerity programme remains.

His election defeat is all the more painful for him as he faced a divided and fragmented opposition.

Fine Gael's election slogan "Let's Keep The Recovery Going" failed to resonate with those who say they felt no recovery, just the austerity which the party enforced.

A collapse in house-building after the crash and failure to build social housing have brought an accommodation crisis and growing homelessness in a country with the EU's youngest population and highest birth rate.

The view from the street

A sharp urban-rural divide also played a role: Ireland's economic revival has been centred around the capital Dublin, in or around which a third of the population lives.

But depression remains in many rural areas, with poor infrastructure such as lack of broadband hindering prospects for economic development. Weaker banks have meant limited funding for the vital small business sector which accounts for over 90% of private sector jobs.

A drive through rural Ireland shows signs of economic blight - and emigration, thought to be a thing of the past during the boom of a decade ago, has returned as a feature of Irish life.

For many middle-aged voters, the loss of a generation of their children to places as far away as Australia has been painful.

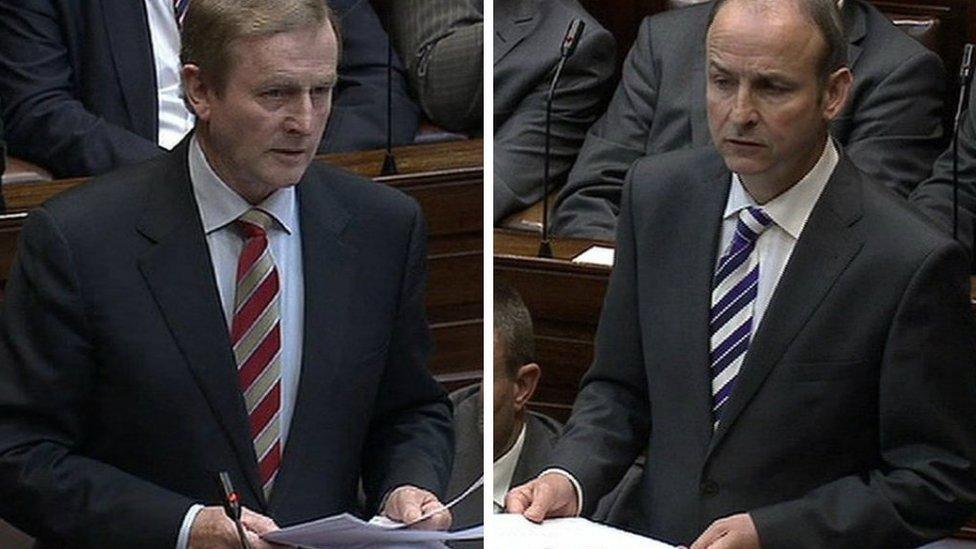

Fianna Fail leader Micheal Martin ruled out a "grand coalition" with his rivals on Thursday night, saying the people had voted to remove Fine Gael from office.

A Fine Gael-led minority government could leave the party at the mercy of its old rival. Another possibility mooted is power-sharing - with a rotating leadership and equal divide of ministerial seats, for the first time ever.

Little will happen between now and early April, due to the St Patrick's Day period followed a week later by the centenary celebrations for the 1916 Easter Rising, likely to be the biggest Ireland has ever seen.

Mr Kenny remains as a nominal caretaker taoiseach, with those of his ministers who kept their seats in the election staying in position for now on the same basis. But big international political storm clouds mean this is unlikely to be a long-term option.

The EU migrant crisis, ongoing economic difficulties in the EU, plus Britain's Brexit referendum - which could have a big impact on Ireland - will intensify demand for a working government in Ireland, even if that means fresh elections.

- Published10 March 2016

- Published11 March 2016

- Published28 February 2016

- Published24 February 2016