Elections are key test for Merkel's future

- Published

Angela Merkel with leading CDU candidate Julia Kloeckner on the campaign trail

Quedlinburg is a tumbling, medieval fairytale of a town. A cluster of half-timbered houses and cobbled streets leads up to a huge hilltop castle.

From its ramparts, you can see for miles across the eastern state of Saxony-Anhalt. It is a region whose political make-up mirrors that of the federal government; a coalition between Angela Merkel's conservative party and the social democrats.

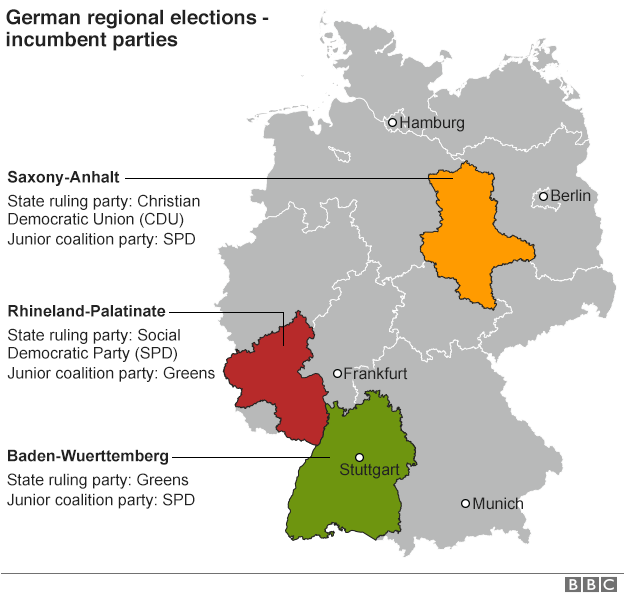

What happens at the ballot box here on Sunday will be closely scrutinised. It's one of three German states holding elections.

They may be regional, but there may be far wider consequences. Because this is the first time German voters get to deliver their verdict on Mrs Merkel's refugee policy.

Already here in Saxony-Anhalt, the political landscape is changing. Polls suggest one in five voters here now supports Germany's populist party Alternative fuer Deutschland (AfD).

Nationally, AfD is taking votes from all of Germany's established political parties - including Mrs Merkel's conservatives.

Some suggest that many of their supporters have abstained from voting in the past.

German power is the real key to Europe

Migrant crisis: EU and Turkey plan one-in, one-out deal

Migrant crisis: Will Merkel be left out in the cold?

Greece needs EU help to avoid chaos, says Merkel

AfD is anti-euro, anti-migrant and controversial; its leader Frauke Petry recently suggested border guards shoot at illegal immigrants.

Its vocal opposition to Mrs Merkel's asylum policy has helped it to gain ground. Analysts also point out that Mrs Merkel has taken her conservatives so far to the political centre that AfD is filling the vacuum on the right.

What Mrs Merkel once dismissed as a small fringe party is likely to do well in the old east where anti-refugee sentiment is particularly strong. No-one really knows why.

Some argue that, 25 years after the wall came down, people have endured so much change that they resist further social shifts.

But it is an ironic position, given that relatively few asylum seekers are actually housed here. Well over a million people arrived in Germany last year, but just 3% live in Saxony-Anhalt.

In Quedlingburg (population 23,000) just 250 people are waiting to hear whether Germany will grant them asylum.

Maureen Wehlenpfennig says the migrant crisis will dominate the election

Even so, local baker Maureen Wehlenpfennig tells me that the refugee crisis has made this a single issue election.

She herself plans to vote for the Social Democrats. The warm buttery smell of vanilla seeps from the oven as she prepares a batch of cheesecakes.

"These elections will be a barometer for the political atmosphere," she tells me. "A wake-up call for people, especially politicians. Obviously none of the right-wingers has a solution and we must be careful to avoid an atmosphere of hatred."

Frank Ruch believes Mrs Merkel can win back voters

Across town, in the wood-panelled grandeur of the town hall, the mayor of Quedlinburg views the regional elections as a test-run for Germany's general election next year. Frank Ruch is one of Angela Merkel's conservatives.

"I support the chancellor," he says "but her welcoming attitude will cost us votes. We'll win voters back, especially those who've gone to Afd, if we use clear language and propose clear measures to solve the refugee crisis."

Mrs Merkel's own approval ratings have tumbled in recent months. But Mr Ruch believes she will recover.

Her government, he points out, has toughened its asylum policy (making it, for example, easier to deport asylum seekers who commit crime).

That, he says, combined with her efforts to secure an international solution, will persuade the electorate.

Now that the Balkans route is, in effect, closed to asylum seekers, there are far fewer people arriving in Germany (several hundred a day rather than the 90,000 who crossed the border in January).

But, in the back room of a pub on a Monday night, that doesn't seem to matter.

AfD is confident of success in Quedlinburg

Ignoring the podium, a local AfD candidate stands holding a microphone in the centre of the room. He is preaching to the converted.

A woman (I guess she's in her 60s) listens intently. Dietlinde Lempel tells me she was angry with Angela Merkel over her approach to refugees. Now she feels hatred.

"She was always bad for this society," she says. "I'm not against diversity but there must be limits. She doesn't have to live with these people - we do!"

It is clear how Lempel will vote.

"AfD speaks to people's hearts. They take people's concerns seriously. No-one else listens."

After the hustings, the candidate Andre Poggenburg tells me that, while his party is accused of racism, homophobia and inhumanity, "this is propaganda from our political opponents who can't fight us with facts".

The party, he believes, will do well in the region. "East Germany has a different mentality. The preparedness and courage to oppose political decisions is higher here than in the west."

It was Angela Merkel who said the refugee crisis would change Germany. The electorate here may yet punish her for that.

- Published10 March 2016