Turkey caught in overlapping security crises

- Published

Women mourn over the coffin of one of the victim's of Sunday's bombing in Ankara

Who'd be in Turkey's shoes right now?

Since July last year, hundreds of soldiers and civilians have been killed in terrorist attacks. Suicide bombs have torn into crowds of demonstrators and tourists. Military convoys have been targeted in the heart of the capital.

A long-running Kurdish insurgency, once thought to be close to resolution after years of painstaking efforts to build bridges, has erupted once more.

The country is awash with Syrian and other refugees. The government has been under pressure to stop them moving on into Europe and prevent would-be jihadis travelling the other way.

How dangerous is Turkey's unrest?

Tears and destruction amid PKK crackdown

Turkey v Islamic State v the Kurds

Washington has been pressing Ankara to play a greater role in defeating the so-called Islamic State (IS) group.

And Russian warplanes have crossed into Turkish airspace, eliciting a hair-trigger response which brought down both a plane and the wrath of a Kremlin once again flexing its muscles in the Middle East.

Overlapping crises

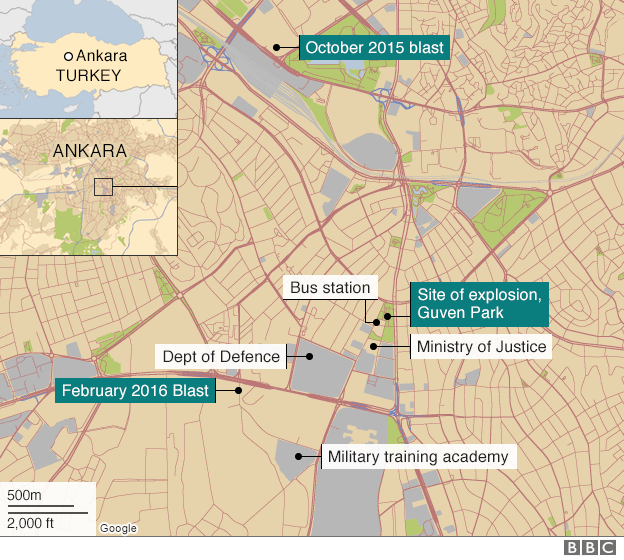

Sunday's car bombing in Guven Park killed at least 37 people

More than 100 people were wounded

Turkey finds itself in the midst of a hideous vortex of overlapping security crises, struggling to tackle one without exacerbating another. With each bombing, the precariousness of Turkey's situation seems even more acute.

Of the half dozen or more bombings over the past nine months (which followed a relatively peaceful two years), most have been blamed on IS. Over the weekend, Turkish forces were firing artillery rounds at IS positions across the Syrian border.

But the government in Ankara blames Kurdish militants, both for Sunday's bombing in Ankara and a mid-February attack on military personnel, which killed 28 people.

The Guven Park explosion was the third deadly attack in Ankara in recent months

A two-year-old ceasefire between the government and PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party) guerrillas broke down last summer. According to the International Crisis Group, more than 340 members of Turkey's security forces have since been killed, along with at least 300 Kurdish fighters and more than 200 civilians.

But the fragile peace had already started to unravel six months earlier, when Kurds accused the government of President Erdogan of doing nothing to stop the IS assault on the northern Syrian town of Kobane.

The government eventually allowed Kurdish "peshmerga" fighters from neighbouring Iraq to join the fight for Kobane. Combined with American air strikes, it was enough to repel the assault.

Reopened wounds

But the spectacle of Turkish troops and police using force to prevent Turkish Kurds from expressing solidarity with their Syrian cousins served to reopen old wounds.

Kurds were convinced that Turkey was secretly in league with IS, allowing foreign fighters easy passage across the border and, many believed, supplying weapons too.

Over the past year, there have been at least four alleged IS attacks on Kurdish activists in Turkey which, Kurds believe, the Turkish authorities have done nothing to prevent.

For its part, the government in Ankara looked on in dismay at the growing relationship between Washington, its Nato ally, and the Syrian Kurdish militia, the YPG, which Turkey regards as an offshoot of the banned PKK.

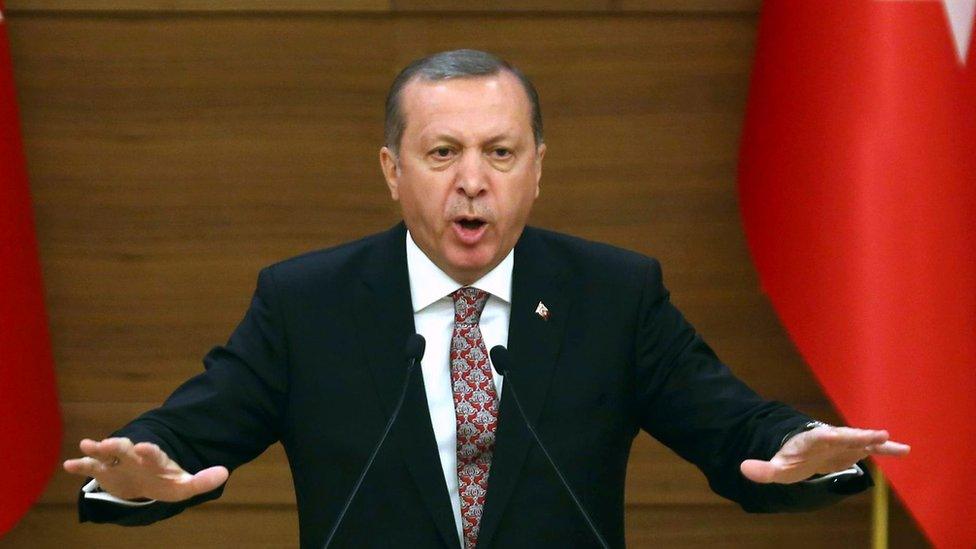

The Obama administration has come to regard the YPG as a key ally in the fight against IS. When US envoy Brett McGurk went to Kobane last month for talks with the YPG, President Erdogan was furious.

"Is it me who is your partner or the terrorists in Kobane?", external he asked.

Pressure cooker

Russia's involvement in the Syrian civil war has added another dangerous level of complexity to this regional maelstrom.

Turkey had long argued that the West's principal objective in Syria should be the removal of President Assad. Now, a newly assertive Kremlin was busy tipping the military balance in favour of Mr Assad.

To make matters worse in Ankara's eyes, the West seemed to be allowing Russia to call the shots.

President Erdogan has been left dismayed at Washington's growing relationship with the YPG and Russia's involvement in Syria

Turkey's shooting down of a Russian jet in November, and the war of words that followed, showed how poisonous this regional dimension had become.

The arrival of thousands of new Syrian refugees at the Turkish border merely served to add to the enormous humanitarian burden which Ankara already felt it was coping with alone.

With Russia dictating events to the south, the EU making demands to the west, bombs exploding on its streets and its own Kurdish areas once again in turmoil, it's no wonder that Turkey feels beleaguered.

It lashes out in ways that seem to make matters worse. Some Kurdish cities now look more like Syrian warzones than parts of a country that aspires to EU membership.

This is a pressure cooker on Europe's doorstep. And the heat is still on.

- Published14 March 2016

- Published13 March 2016