Labour law reform: Hollande's last throw of the dice

- Published

President Hollande is fighting for his political legacy

It is easy to find one's brain befuddled before the complexity of the French Labour Code.

In fact, with more than 3,500 pages to its latest edition, plus vast amounts of supplementary case law, it is not just easy to be befuddled - it is inevitable.

And let us venture further. Befuddlement is not merely incidental to the French Labour Code, external. It is part of the very design.

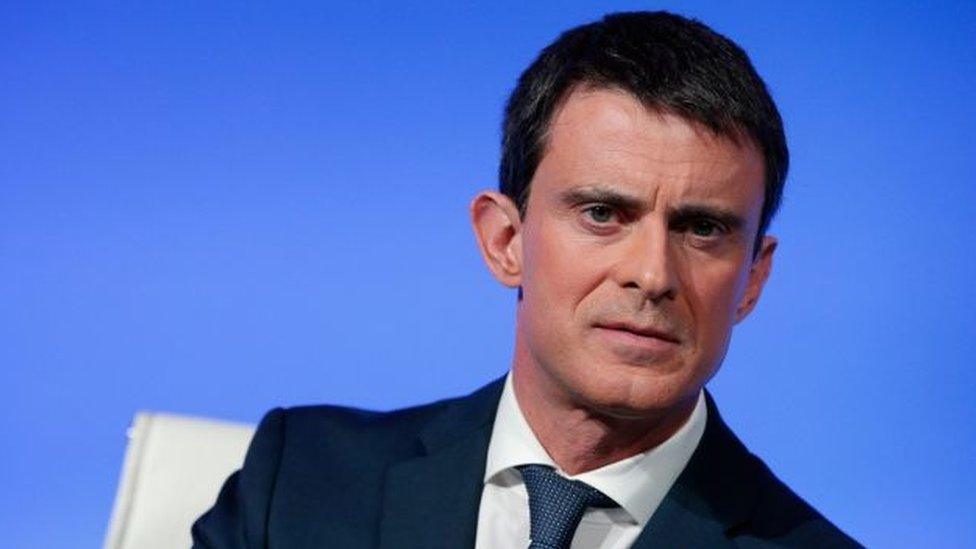

There cannot be more than one person in several hundred thousand who understands the latest reform plan being circulated by Prime Minister Valls.

On Monday, as the various "social partners" stopped before television cameras outside the prime minister's offices, their reactions to the plan (revised version) were like rival exegeses on the Talmud.

France's working week:

France's 35-hour working week was approved by Lionel Jospin's socialist government in 2000. Anything more is legally considered overtime.

Previously the legal duration of the working week had been 39 hours, established under Francois Mitterrand.

Some employers say the 35-hour week has pushed up costs, and made it difficult for France to compete in global markets.

The current government wants employers to be able to negotiate longer hours and lower overtime pay with staff, arguing that it would help to reduce the country's double-digit unemployment rate.

The Medef business leader complained that a compensation ceiling imposed by tribunals in the case of proven wrongful dismissal would no longer be "prescriptive" but "indicative".

The CGT union leader complained that new guarantees limiting the justification of economic dismissal on the basis of a company's French - rather than international -- performance were insufficient.

The FO union leader regretted that a worker's Compte Epargne Temps (Personal Time Savings Account) would not be included in the future Compte Personnel d'Activité (Personal Activity Account).

And that it was also unclear where the Compte Penibilite (Hardship Account) and the Compte Personnel de Formation (Training Account) would fit in.

Labour Minister Myriam El Khomri has worked on the reforms

One students' leader was pleased that there was a commitment to the Garantie Jeunes (Youth Guarantee Scheme). But another supported more strikes because under the law overtime pay can be negotiated at 10% rather than 25%.

One "reformist" union leader was happy because the "philosophy" of the law was to devolve negotiations to company rather than sector level. One "hardline" union leader was angry for exactly the same reason.

And a business leader said whatever the "philosophy", it was all irrelevant because the law's original intention - to allow small businesses to make deals directly with workers, rather than unions - had just been removed in the revised version.

How any ordinary person is supposed to make head or tail of this - let alone decide whether the maze of new clauses to the Labour Code will actually bring down unemployment - is beyond understanding.

Judgement time

The purpose of the new "Law on New Protections for Businesses and Workers" is to do precisely that - tackle France's crippling unemployment (five million if you include all categories).

It is President Hollande's last throw of the dice, before elections next year.

Early on, Hollande had said he should be judged as head of state on whether he had "turned the unemployment curve around". But this he has singly failed to do.

Some 600,000 more people are in the dole queues today than there were in 2012. Most of them are young people - another group who the president promised to pay special attention to when he took office.

Equally damning: for all France's vaunted social protection, 90% of new job contracts today are short-term "CDDs", which normally last just three months. Employers are too scared to offer the sacrosanct "CDIs" - which are permanent.

So with the clock running out and his unpopularity at new highs, the president has cast in his lot with the economic liberalisers in his Socialist Party - that is to say Prime Minister Valls and Economy Minister Emmanuel Macron.

The new law was intended to start the same process that has long been under way in France's neighbours, loosening up the labour market and reducing employee protection, but in return creating new jobs.

There have been protests against the planned reforms

A month on, and we have seen the reaction. A day of strikes and protests last week was not hugely followed - but sufficiently so as to rattle the government, especially as a large part of the Socialist Party is itself opposed to the changes.

So now we have the Khomri Law, external (after Labour Minister Mariam El Khomri) Mark II. Under pressure from the street, Prime Minister Valls has removed several clauses, adapted others - while (he says) remaining true to the reforming spirit of the original.

But - and here is the point - who is to know?

As we saw at the start, the content of the law is bewildering in the extreme. Only a handful of people understand it, and they themselves have differing interpretations on what effect it will actually have on the jobs market.

All that can said with certitude is that it is a million miles from the radical, game-changing reforms that have been introduced in Germany and the UK.

In France, once again, it is textual fudge that will win the day.

Prime Minister Manuel Valls is keen to push through reform

Politically it will be a master-stroke, probably allowing the law to go through with a couple of "reformist" unions onside and avoiding all-out confrontation with the street.

Judgement on its practical effect will be deferred because - after all - it takes years for complex changes like these to work their way into the jobs system.

And by that time the law will be forgotten - apart, that is, from an extra hundred extra pages in the Labour Code.

- Published9 March 2016

- Published14 January 2016