Pope Francis's reforms polarise the Vatican

- Published

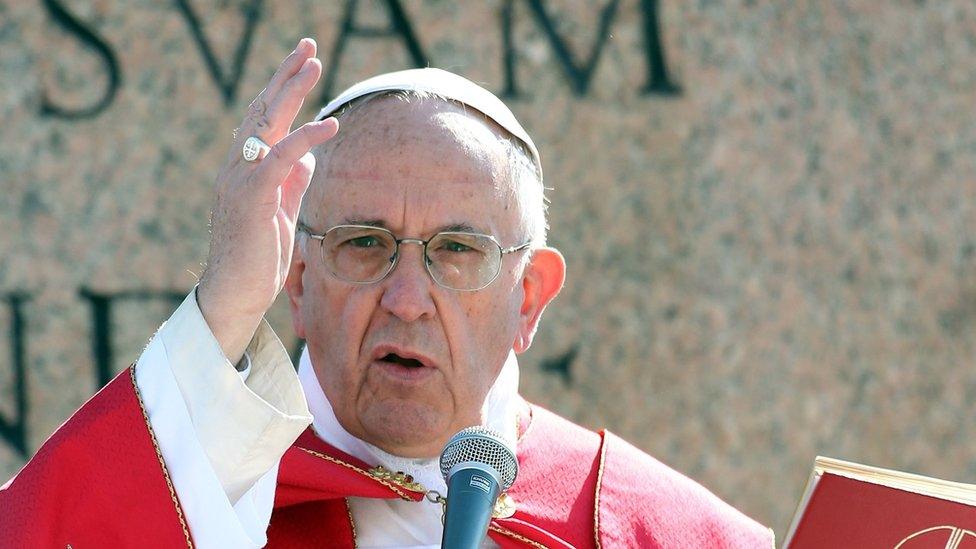

Rarely has a pope been more popular with the people.

A survey of Pope Francis's standing, external around the globe shows that he is seen positively by well over half the world. Some 54% say their opinion of him is favourable and just 12% see him unfavourably.

That means that his overall rating in the WIN Gallup International poll, or net score, this Easter is 41% (with rounding taken into account) - higher than any secular world leader.

US President Barack Obama topped a similar poll of political leaders by the same company. He was seen favourably by 59% but unfavourably by 29%, giving him a net score of only 30%.

@franciscus

Last weekend, Pope Francis joined Instagram, external with a photo of himself at prayer, adding to the followers he already enjoys on Twitter, external (8.9 million at time of writing).

The Pope's first post on Instagram

Three years into his papacy, Francis has enjoyed enormous goodwill and positive PR around the globe, winning hearts and minds not just among Roman Catholics (85% have a favourable opinion of him), but also from other religions and non-religious people. He is regarded favourably by:

65% of Jews

53% of Protestants

51% of atheists and agnostics

33% of Buddhists

28% of Muslims

However, the one constituency that was not polled in this survey, but whose results would have made for interesting reading, was the Curia itself, the Vatican bureaucracy in Rome that Pope Francis promised to shake up at the start of his papacy.

Honeymoon over

Within the Curia, the Pope has polarised opinion, much as he has done between more conservative and liberal Catholics, even though he has not changed Catholic teaching and remains a staunch and vocal opponent of abortion, recently terming it a crime and "an absolute evil".

While his focus on mercy and interpreting the gospel with compassion have been welcomed by many, not all of Pope Francis's reforms are proving so popular and some are encountering stiff internal resistance. Any honeymoon period within the Curia for this pope is long since over.

Pope Francis

Born Jorge Mario Bergoglio on 17 December 1936 in Buenos Aires, of Italian descent

Ordained as a Jesuit in 1969

Studied in Argentina, Chile and Germany

Became Cardinal of Buenos Aires in 1998

Seen as orthodox on sexual matters but strong on social justice

First Latin American and first Jesuit to become pope, the 266th to lead the Church

Said to be a football fan, supporting Buenos Aires team San Lorenzo de Almagro

Outside the Curia, some - especially those on the more liberal side of the Church - say that more substantial and concrete progress will be needed in Francis's fourth year in office on the main challenges facing this papacy if there is truly to be a "Francis Revolution".

They cite the four most pressing issues as:

reforming the Curia

dealing with the long and shameful history of cover-up of child abuse within the Church

trying to ensure financial rigour at the Vatican

shaping the Church's approach towards homosexuality in a way that alienates neither the growing Church in the developing world, nor the faithful in much of the developed world where same sex marriage is legal and increasingly unremarkable

October's convention of the Synod of Bishops left many with concerns about the unity of the Church

Pope Francis began his reforms by assembling a special commission of cardinals to advise him (the "C9"), a kind of papal cabinet, and is gradually pushing through the restructuring of parts of the Curia.

One of his first reforms was to the Vatican's own communications departments and more structural reforms or mergers of departments ("dicasteries") are due this year.

So far, such structural reform at the Vatican has remained incremental, although the clean-up under Cardinal George Pell of Vatican finances and the Vatican Bank is perhaps the most advanced of those changes, with Pope Francis recently setting new financial and accounting guidelines for the department that creates saints.

Divided over devolution

This pope has made very clear his dislike of clericalism and his wish for a "healthy decentralisation" of the Church is an idea that sends shivers down the spine of many within the Curia and the wider faithful.

His push for more power to go to the peripheries is far from popular with those who currently wield it, but is also feared by many Catholics who believe that greater devolution is a road down which the Church should not go, lest it dilute or break up its universal message and sow confusion among the faithful.

For others, dealing with the horrific legacy of child sex abuse is also proceeding too slowly.

Peter Saunders' removal from the Vatican's commission examining clerical sex abuse has been controversial

Pope Francis has termed sexual abuse "an ugly crime" and has set up a commission to fight it, although the recent departure of Peter Saunders,, external one of only two survivors of such abuse on the commission, cast doubt on how effective it can be.

Mr Saunders and others believe that the Vatican is still not doing nearly enough to root out current child abuse by clerics or deal swiftly and transparently with perpetrators.

Likewise the Synod of Bishops, which was convened to discuss the family, raised hopes among more socially liberal Catholics that real changes might be afoot.

Those hopes centre on a change in the Church's attitude towards the divorced and remarried being allowed to take communion again, as many in Germany and elsewhere wish, and in a more welcoming attitude towards gay Catholics - although same sex marriage was pushed firmly off the agenda.

The papal exhortation - or what Pope Francis thinks should happen next as a result of those Synods - is due to be released any day now. Whatever the Pope says in it is likely to be claimed by both sides as a victory.

Yet some fear that its conclusions may risk further dividing a Church that is increasingly riven by internal disagreement over the direction that its own structure and hierarchy needs to take, even as well over half the globe cheers on this pope of extraordinary personal popularity.