Brussels explosions: Why has Belgium's capital been attacked?

- Published

The attack on Brussels airport raises questions about levels of security

These are the darkest days Belgium has known since World War Two, according to one Belgian politician.

The attacks, claimed by jihadist group Islamic State (IS), murdered people at Brussels international airport and on a metro train in the heart of the Belgian capital.

And the targets were among the most sensitive in Europe. Brussels is home to the EU, Nato, international agencies and companies, as well as Belgium's own government.

Why has Brussels been attacked?

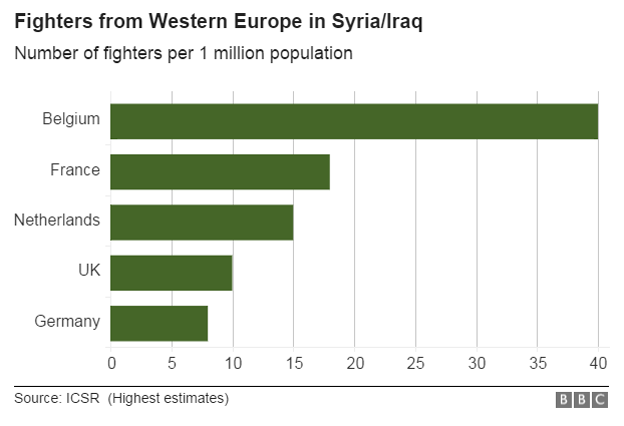

Not only is Brussels a high-profile target for Islamists, Belgium has struggled with Islamist groups for years and some 500 of its citizens have been lured into fighting for IS in Syria and Iraq.

Several cities have housed Islamist cells, but the most active have been in Brussels and in the south-western suburb of Molenbeek in particular - an area with a high ethnic Moroccan population and a high rate of unemployment.

Several of the bombers and gunmen who targeted Paris last November, killing 130 people, had been living in Molenbeek. The main suspect not to die in the Paris attacks, Salah Abdeslam, returned to Belgium the day afterwards and managed to evade police until 18 March. He and an accomplice were captured alive, again in Molenbeek.

Many Belgians were expecting a response from jihadists. "I had certainly expected something else would take place, but not that it would happen on this scale," says Belgian jihadism expert Pieter Van Ostaeyen.

More about the attacks

Why have so many Belgian Muslims been attracted to jihadist violence?

More Belgian Islamists have gone to fight for IS than from any other European country per capita. Almost half have come from Brussels.

But it is not just Brussels, and Molenbeek in particular, that has had a problem with jihadism.

Islamists have also emerged from other Belgian cities, including Verviers and Vilvoorde and most significantly Antwerp, where the now disbanded group, Sharia4Belgium, recruited the first Belgian fighters for Syria.

Many trace Belgium's problem with Islamism to its decision in the 1970s to allow Saudi Arabia to construct the city's Great Mosque.

The Saudis also sent over a large number of imams to preach a hardline, Salafist form of Islam to a recently arrived Muslim population.

Critics believe the Salafist influence, combined with a lax approach by authorities over a 20-year period, helped jihadism to spread.

And then there was anger when the government changed tack, banning women from wearing a full Islamic veil in public.

Pre-planned attacks or revenge?

So were Tuesday's bombings retaliation for last Friday's success in capturing two Islamists alive? The arrests were clearly a blow to IS and Belgian jihadists.

Abdeslam has been described as the logistics expert in the Paris attacks. He rented flats, drove militants across Europe and bought bomb-making equipment. Days before his arrest, an accomplice who had been hiding with him, Mohamed Belkaid, was shot dead by police. He had been wrapped in an IS flag.

Abdeslam (pictured by CCTV in November) was arrested on 18 March and has been giving information to Belgian police

"What seems likely is that attacks were already being planned and due to specific arrests they were accelerated because the terrorists knew they were being hunted," says Prof Dave Sinardet of Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Free University Brussels).

In fact Brussels had already tried to guard against multiple attacks following an apparent threat 10 days after the Paris attacks. For several days the city went into lockdown, much as it did on Tuesday, with public transport at a standstill and people told to avoid travelling around.

Did Belgium's security forces fail?

Three men with suitcases packed full of explosives were able to enter the airport at Zaventem and blow themselves up. An hour or so later another man was able to enter a metro train a stone's throw from the headquarters of the EU and blow himself up.

Security forces had a dry run in November, the terror threat was at its second highest and soldiers were already deployed on the streets of several cities.

Soldiers have been visible in major Belgian cities for some months

A beleaguered police force has clearly buckled under the weight of an almost non-stop Islamist threat. And yet it suffers from institutional problems too.

Brussels is a relatively small European capital, and yet it still has six police zones. Its CCTV system is far less developed than London or Paris.

"It's clear there are inefficiencies in the level of security services. For years we haven't put enough energy into issues of security and terrorist threats," says Prof Sinardet. However, he argues this kind of terrorist attack is very difficult to avert, as witnessed in Madrid, London and Paris.

Are further attacks likely?

A CCTV image of three men said to be suspected of being behind the airport attacks has emerged

For Belgians, this is the most awkward question. Several suspects are still urgently being sought by police.

One of the suspected airport attackers (the man in the hat on the right of the picture) was on the run on Tuesday and police were already actively hunting two other suspects who were both accomplices of Salah Abdeslam.

One of the missing Paris suspects is Mohamed Abrini, and nothing has been heard of him since November last year.

It is unclear if another Paris suspect, Najim Laachraoui, is still alive. Unconfirmed reports suggest he blew himself up in the airport attack. His fingerprints were found in the Brussels flat where Paris bombs were made, and he may have been the bomb-maker.

After the Paris attacks, US counter-terrorism expert Clint Watts wrote of the "iceberg theory of terror plots, external": for every attacker, there were usually several others helping to facilitate the plot, but what one saw was just the tip of the iceberg.

Mr Watts believes that the Brussels bombings are the fallout from the Paris attacks. What is not clear is whether those still on the run plan further bloodshed.