Karadzic verdict vital to Bosnia's future

- Published

Radovan Karadzic has been on trial for eight years

On 5 February 1994, a mortar bomb fell out of a clear blue sky into the heart of a crowded marketplace in central Sarajevo.

It struck an overhead canopy on the way down and exploded just above the heads of people gathered there.

Sixty-eight people were killed in an instant, and 250 more were injured.

Bosnia's war had been raging for two years, and mortar attacks were commonplace in Sarajevo. They were part of a deliberate war against civilian targets.

But not since the war had begun in April 1992 had so much life been destroyed at a stroke.

It changed the dynamic of the war.

The Western powers, for the first time, took sides in the conflict, warning the Bosnian Serbs they faced military intervention by Nato if the atrocities did not stop.

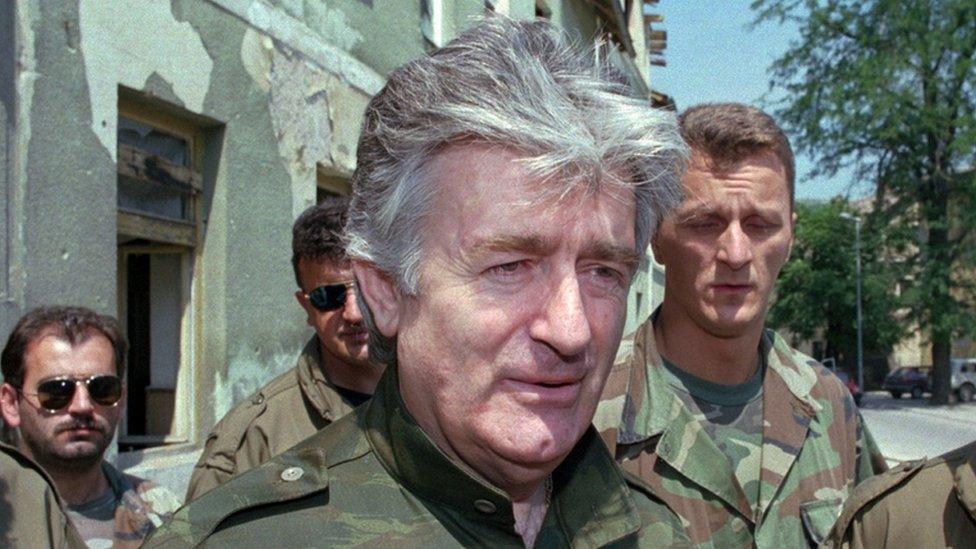

Radovan Karadzic was the political leader of Serb nationalist forces.

As usual, he denied his forces had been to blame for the attack, saying the bodies picked up from the carnage at the marketplace were either those of people who had died from natural causes in hospital, deposited there covertly, or shop-window mannequins taken to the scene to fool Western TV crews.

I was among the TV crews in the city that day.

Beginning of the end

In the days that lay ahead, I went to the funerals of those who had been killed and watched relatives hurriedly lower coffins into hastily dug graves and then quickly depart, for fear the funeral parties themselves would be attacked from Serb positions in the hills above then city, as they had been in the months of war already past.

In retrospect, this was the beginning of the end for Radovan Karadzic.

From then on, he was taking on not just a much weaker enemy on home soil, but international public opinion.

Until then, the Western allies had been inclined to see all sides as equally guilty.

But now they were increasingly conscious it was the Bosnian Serbs who were keeping the war going.

A year later, led by the US, they intervened decisively, external, bringing the war to an end with an aerial bombing campaign that allowed Bosnian Croat and Bosnian government forces to start rolling back many of the military gains the Serbs had made during the war.

By the time the leaders of the former Yugoslavia gathered at Dayton, Ohio, for the talks that would bring peace, Radovan Karadzic was not among them.

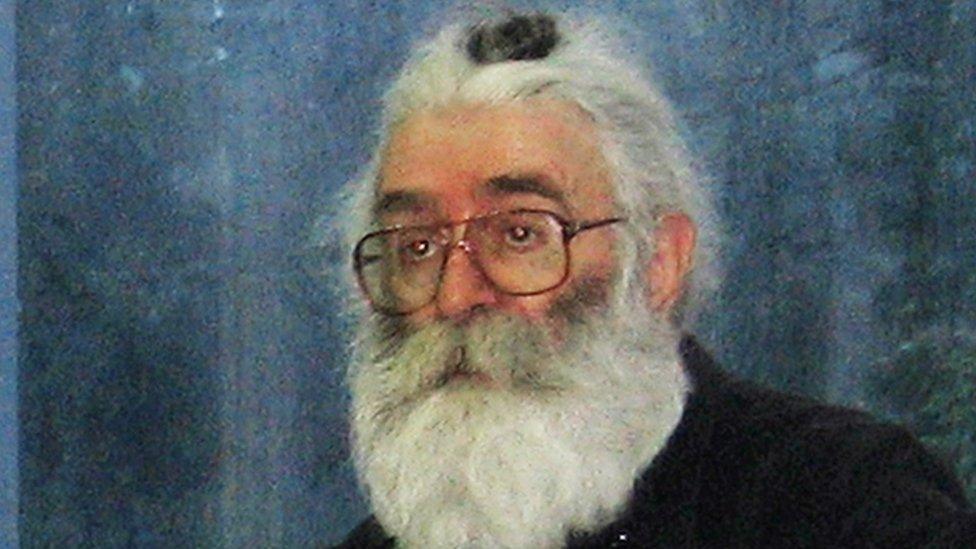

Mr Karadzic assumed the alternative identity of Dragan Dabic

He had been indicted by the war crimes court - the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) to give it is formal name - established by United Nations Security Council resolution in 1993.

For most of the next 13 years, he would be on the run, arrested finally in Belgrade in 2008 disguised as "Dr Dragan Dabic", an alternative health guru living openly in the Serbian capital, even addressing public meetings and appearing on video recordings in a long white beard and hair tied in a knot on the top of his head.

He was handed over to the Hague court by a reformist Serbian government anxious to turn the page on its own country's complicity in war crimes.

Radovan Karadzic presided over a reign of terror in Bosnia that lasted 1,000 days.

The capital city was besieged by his forces and bombarded almost daily.

Nearly 12,000 died in Sarajevo alone, external, many of the civilians apparently targeted deliberately not only by mortar and artillery fire but by the much more intimately menacing presence of snipers hidden in city centre apartment blocks.

In November 1994, during a ceasefire that had held for many weeks, Djenana Sokolovic, external was out collecting wood.

She had been visiting relatives with her two young children.

Mr Karadzic is accused of orchestrating atrocities in Sarajevo

A burst of gunfire rang out from a building on the other side of the front line.

Mrs Sokolovic was hit in the abdomen.

She was taken to hospital by UN peacekeepers.

What she didn't know until later was the bullet that passed through her also struck her seven-year-old son, Nermin, in the head and killed him instantly.

Mrs Sokolovic was named in Mr Karadzic's indictment.

She had already given evidence in the trial of another accused man.

"I would go to the Moon to get justice for my son," she told me.

"It meant so much to me to go to the Hague.

"I would go again tomorrow if they asked."

Ethnic cleansing

What happened in Sarajevo was captured in graphic detail by the international journalists who, shortly after the start of the war, set up home in the city centre Holiday Inn.

It was hard and dangerous work, but the war was, at least, accessible to us.

It played itself out in front of your camera lens.

Much more difficult to document was the campaign known as "ethnic cleansing" taking place elsewhere in the country.

From April 1992 onwards, in northern and eastern Bosnia especially, Serb forces carried out a campaign of forced removals.

Hundreds of thousands of non-Serbs were driven from their homes.

Often these homes were torched or dynamited.

You could drive through the countryside and pass village after village that had been levelled.

It was the result of the war, Serb leaders would say.

Concentration camp survivor Kemal Pervanic: "Karadzic destroyed our community - it's going to take many generations to recreate it"

But interviews with survivors told a different story.

Kemal Pervanic was 24 years old when Serb forces came to his village, in the Prijedor municipality of north-western Bosnia.

The civilian people were rounded up.

They had no weapons and put up no resistance.

The men were separated from the women and children, who were put on a fleet of buses and driven away to become refugees in parts of the country the Serbs did not claim as their own.

The men were taken to internment camps and held there.

Mr Pervanic was held for seven months.

"It was a living hell," he said.

"We had very little food.

"We couldn't wash.

"We slept on concrete or gravel.

"Men were being beaten and killed, women were raped.

"I could hear all this through the wall in the room I was being held in.

"You never knew from one minute to the next whether you would be killed."

Mr Pervanic showed me a school photograph taken in 1983, when he was 15.

"The boy at the bottom left is Senad," he said.

"He was taken with me to Omarska camp.

"He died after being shot in the neck by a guard who was handling a gun carelessly.

"The one further along the front row was one of the camp guards, and behind him is a boy I shared a desk with in school.

"I saw him in the camp too, wearing his [Bosnian Serb] uniform and carrying a rifle."

In the picture, Serb and Muslim children sit side by side, intermingled, utterly unconcerned about ethnic distinction.

"This is what Karadzic destroyed" Mr Pervanic said.

"It will take generations to rebuild this kind of community."

Mass murder accompanied the ethnic cleansing.

Leaders of the non-Serb communities, especially Muslims, were rounded up and killed.

The aim was to make it impossible for Serbs and Muslims ever to live together again.

This was how the ethnically pure Serb state in Bosnia was to be built.

There are lasting scars from the massacre at Srebrenica

Bosnian Serb political and military leaders were absolutely open in their determination to dismember Bosnia.

They saw it as an illegitimate state and an affront the the sovereignty of the Serbian nation.

The long-term aim was to carve out a Serbian territory that would claim about two-thirds of the territory of Bosnia-Hercegovina, then unite with Serbia proper to create a Greater Serbian state.

The campaign of ethnic cleansing culminated, in July 1995, in the now notorious massacre at Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia.

Here, in the beginning, local Muslims had armed themselves and had resisted the ethnic cleansing.

The enclave had been besieged by Serb forces for three years, and many had died on both sides in the fighting.

When Serb forces overran Srebrenica, external, up to 8,000 Muslims were murdered in the space of a few days, and their bodies dumped in mass graves.

It was the atrocity that finally tipped the world into military intervention - and the war was finally over within a few weeks.

Karadzic Timeline

1945: Born in Montenegro

1960: Moves to Sarajevo

1968: Publishes collection of poetry

1971: Graduates in medicine

1983: Becomes team psychologist for Red Star Belgrade football club

1990: Becomes president of Serbian Democratic Party

1990s Political leader of Bosnian Serbs

2008: Arrested in Serbia

2009: Trial begins at The Hague

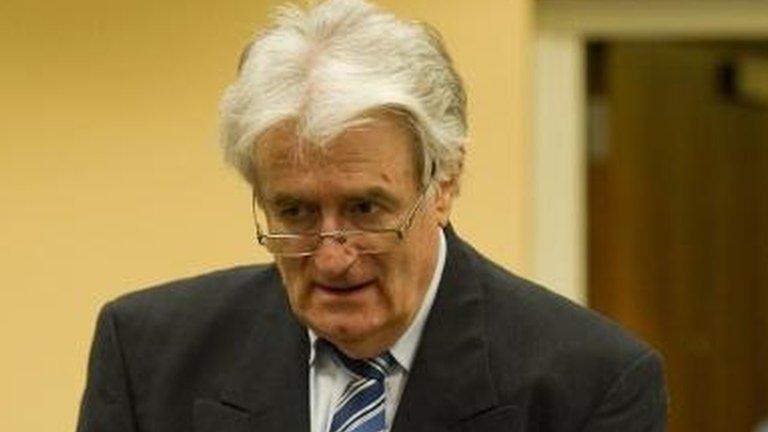

Radovan Karadzic faces 11 separate charges, including genocide, extermination, forced removal, and crimes against humanity.

His trial - during which he has represented himself - has lasted eight years.

The prosecution's most difficult task will have been to draw a direct line of culpability from the men who committed the crimes on the ground to Mr Karadzic in person.

He denies everything and has told the court he expects to be acquitted.

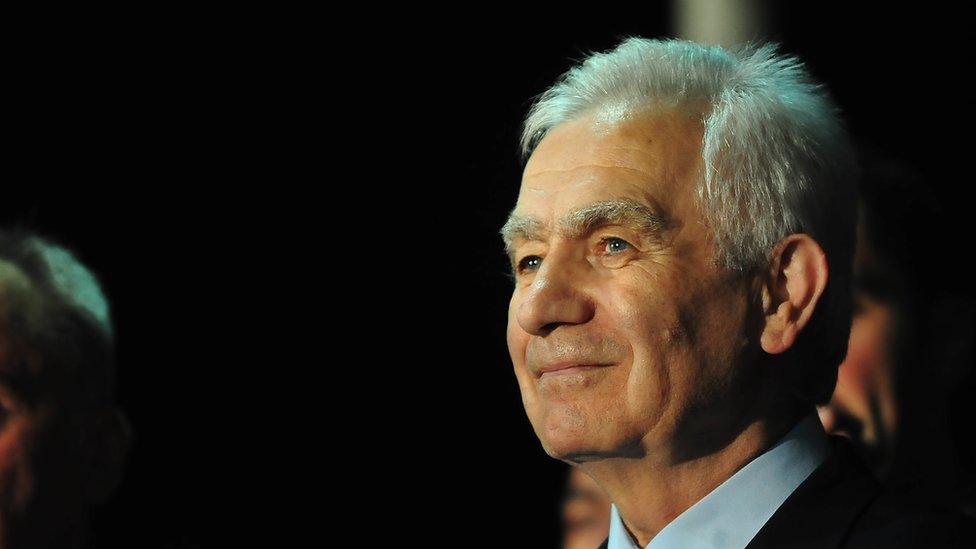

One of his closest lieutenants during the war was Momcilo Krajisnik.

He was found guilty of war crimes and sentenced to 20 years in jail.

Momcilo Krajisnik was welcomed as a returning hero after release from prison

He served his sentence mostly in British prisons, and was released in 2013 after serving two-thirds of his term.

He returned to the Bosnian Serbs' wartime capital of Pale, outside Sarajevo, and was greeted as a hero by a huge crowd of exuberant Serbs.

Some of them waved portraits of Mr Karadzic.

"Radovan Karadzic is absolutely a hero for the Serbian people," Krajsnik told me recently.

"They see this [trial] as an injustice against them.

"Karadzic is absolutely a victim and a hero.

"I can say with safety that he is not guilty of the crimes he is accused of."

Bosnian Serb public opinion remains deeply in denial about the crimes committed in the name of the Serbian nation 20 years ago.

Bosnia remains divided and unreconciled.

The Hague tribunal has indicted more than 160 and brought more than 120 to justice.

Some have been acquitted, others sentenced to long prison terms.

But it took thousands to commit those crimes, and many of the foot soldiers of the ethnic cleansing will never face trial.

Many, 20 years on, are still at large, still in their posts in police stations and town halls across the country.

Why does the Karadzic verdict matter?

"It matters," says Mr Pervanic, "because if he, as the leader, was not held to account, it would be a signal to future generations that you can start a war, cause the deaths of tens of thousands of people, and it'll be fine. Nothing will happen to you."

- Published18 March 2016

- Published16 October 2012

- Published24 March 2016