Bewildered migrants await fate on Lesbos

- Published

Migrants taken to camps complain they are "treated like animals"

Every day this week has brought hundreds more migrants across the Aegean sea to the Greek shore.

Many say they know nothing about the new deal struck between the EU and Turkey, which could mean their stay here is short-lived.

Those who had heard rumours of imminent deportations clearly hoped they were not true.

"I have dreams for my family. A happy family. In Europe!" Rada Ali tells me, her eyes sparkling and with a big, warm smile.

Her family from Damascus were in a group of more than 60 rescued from a dinghy this week by the Greek coastguard.

Rada and Mustafa say they have no idea what applying for asylum means

"Back to Turkey? No. Turkey, no!" she says, at the prospect of being returned there. Rada tells me she plans to travel to Sweden to be reunited with her eldest son.

Instead, like all new arrivals, she is soon being bussed to a detention facility. On board with her are dozens of children.

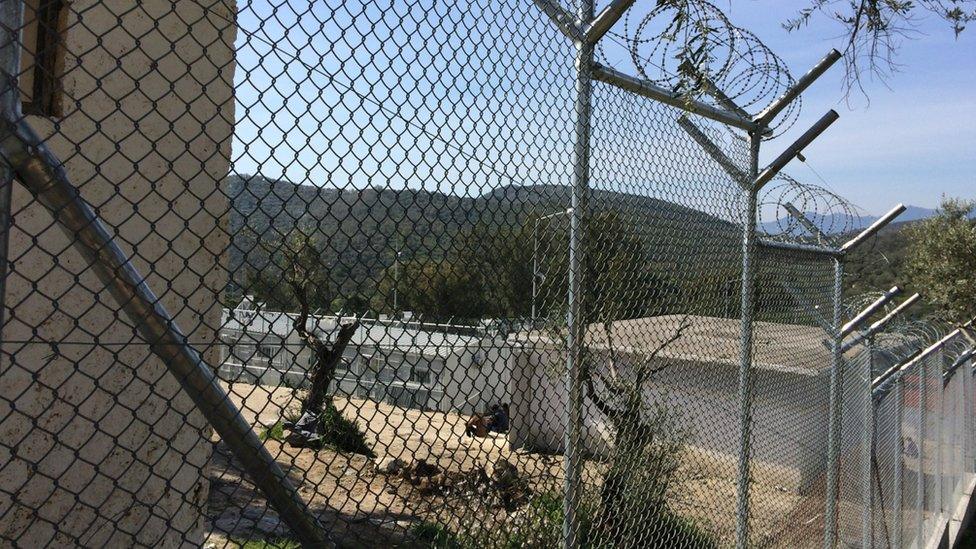

A day later I find her in tears behind the high fence and barbed wire of the migrant camp.

Her smile crumbles as she tells me the place is overcrowded and the family have to sleep outside, on the floor. It's cold at night and her son Mustafa says they queue for up to four hours for food.

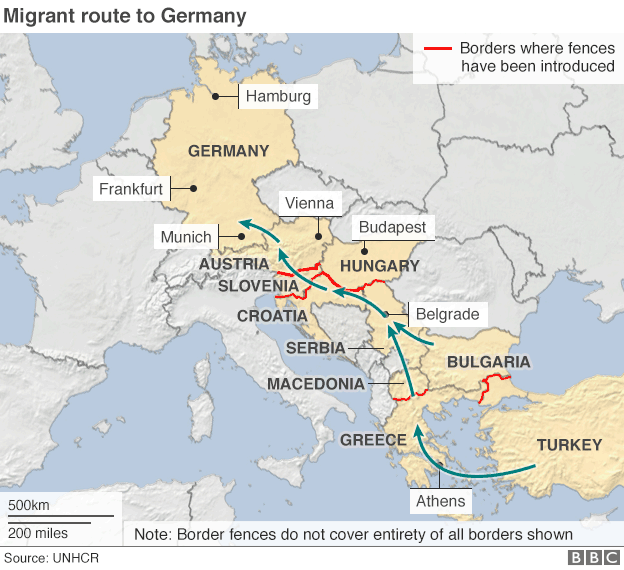

Turkish ferries will be used to transport migrants from Lesbos

The UN refugee agency and others have stopped their humanitarian services at the facility, in protest at the indiscriminate, forced detention of asylum seekers.

"Everyone is worried about April 4th," Mustafa tells me. "They've heard that some people in the camp will be sent back to Turkey then, but no-one knows who or how."

A Greek official told us from Athens that the first to go would be those who had not requested asylum. That's primarily "economic" migrants. But Mustafa and Rada have no idea what "applying for asylum" even means.

"We were told just to stay here," Mustafa says, bewildered. Others who crowd around are clearly angry.

"They say you're under arrest, but I never went to trial!" a Syrian who calls himself Roy tells me. "They just put us here like goats. Like animals."

Down in the port, Turkish passenger ferries are on standby to take the first group of returnees across the sea. But how that plays out in practice, is still very unclear.

Key points from EU-Turkey agreement

Returns: All "irregular migrants" crossing from Turkey into Greece from 20 March will be sent back. Each arrival will be individually assessed by the Greek authorities.

One-for-one: For each Syrian returned to Turkey, a Syrian migrant will be resettled in the EU. Priority will be given to those who have not tried to illegally enter the EU and the number is capped at 72,000.

Visa restrictions: Turkish nationals should have access to the Schengen passport-free zone by June. This will not apply to non-Schengen countries like Britain.

Financial aid: The EU is to speed up the allocation of €3bn ($3.3 bn; £2.3 bn) in aid to Turkey to help migrants.

Turkey EU membership: Both sides agreed to "re-energise" Turkey's bid to join the European bloc, with talks due by July.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.