Jihadist shadow hangs over Georgia's Pankisi Gorge

- Published

Jihadist Omar Shishani, originally from Pankisi, is thought to have inspired dozens of young residents to join so-called Islamic State

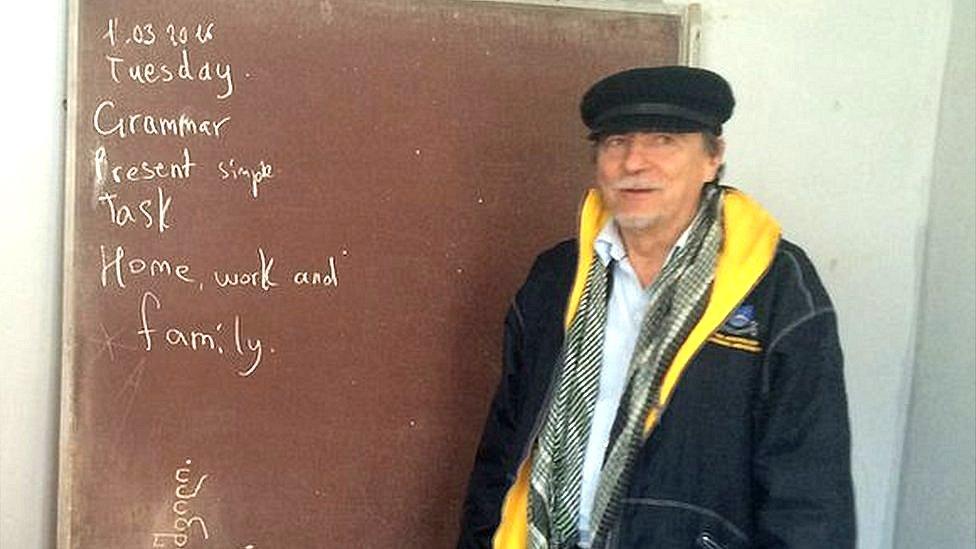

"This is one of our classrooms; it's very Dickensian," says Vladimir Lozinski as he ushers me into a narrow room with five or six tables and a blackboard. The children rise up as we enter.

Mr Lozinski helped set up the Roddy Scott Foundation English language school in the Pankisi Gorge, in north-eastern Georgia, in 2008. The foundation is named after a British journalist killed in the mountains nearby in 2002 while documenting the Russian-Chechen war.

"Pankisi was a pretty wrecked and forgotten place in many ways. The only thing this valley was famous for is the Chechen fighters that fought the Russians over the mountains," he says.

"Even for the Georgian government it was a 'no-go' area: you would have been kidnapped. They cleaned them out eventually."

Vladimir Lozinski is concerned by the rise of radical Islam in Pankisi

These days, the Pankisi Gorge has won greater notoriety as the home of Omar Shishani, a senior commander of so-called Islamic State (IS). The US says he was killed last month in north-eastern Syria although his death was not confirmed by IS.

Shishani was a former officer in the Georgian army. His real name was Tarkhan Batirashvili and his father still lives in the valley. He is thought to have inspired dozen of young men from Pankisi to join the fight in Syria.

A former imam in the village of Jokolo in the Pankisi Gorge was jailed for 14 years in Georgia in February for helping recruit young men for IS.

Aiup Bochashvili's co-defendants were also given lengthy prison terms.

At the local community centre I met a woman who had recently learned of her 25-year-old son's death in Syria. Her hands were folded across her chest, her eyes red from crying.

Although reluctant to give an interview, she told me that her son left the valley five years ago; she had been to visit him in Syria twice, and she had even brought him a wife from Pankisi.

Sleepy village

In the village of Duisi, a dirt road leads to Khadori hydro power plant, built by a Chinese company in 2004.

It was the last time local men had regular work here, says Lia Margoshvili, Pankisi resident and a school manager at the Roddy Scott foundation.

"We have lots of problems with unemployment, there is no work, there is no money," she says.

A single new building stands out in Duisi. It is a mosque.

Mosques have appeared in every village in the Pankisi Gorge, including here at Duisi

"In the past few years mosques have appeared in every village in Pankisi," says Ms Margoshvili. "They opened Arabic language courses at mosques and kids go and learn Arabic, but nobody knows where the money is coming from."

The majority of Pankisi's 10,000 population are Kist Muslims, an ethnic group of Chechen or Ingush origin who settled in Georgia two centuries ago.

Despite 200 years of common history, people here feel marginalised from the rest of the country, says Shorena Khongushvili, editor at the recently established community radio station RadioWay.

"We have 12 villages here. These are traditional people. This is a society that usually feels separated from the outside world," she says.

"The Syria thing became very popular. We don't want Pankisi to keep this image, we want it to be more open."

The Georgian government does not have a strategy for dealing with Saudi theological interpretations of Islam popular in Pankisi, according to Arabic studies professor Giorgi Lobjanidze. He has translated the Koran into the Georgian language and takes part in seminars here.

A group of men listen to Professor Lobjanidze's lecture on Islam

"If we had an opportunity to create a university of Islamic theology and teach it in Georgian here, it would have been great to educate these people about Islam without the third parties."

At the Roddy Scott Foundation I enter an older class of teenage girls with Vladimir Lozinski. Most are wearing hijabs.

"Do you listen to music? Who has a favourite singer?" Vladimir asks.

The class is silent until the teacher responds: "Vlad, according to their religion they don't listen to music," she says.

This revelation seems to unsettle Vladimir.

Most of the Pankisi Gorge's 10,000 residents are Kist Muslims who originate from Chechnya

"They should be listening to music because it's good for their soul. This thing that's creeping in. They are kids, they've got to have fun."

The Georgian government is also concerned about the rise of fundamentalist Islam in Pankisi. As part of a drive to integrate the valley into wider Georgian society it has started a recruitment drive to encourage young men to join the military.

In January, Georgia's President Giorgi Margvelashvili made a high-profile visit to Pankisi along with the US ambassador. It was seen as a public rebuttal to a statement by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov that jihadist training camps existed in Pankisi.

"Things are changing slowly," says Lia Margoshvili. "The authorities have finally realised that if they keep neglecting Pankisi - it will become a much bigger headache for them in future."

- Published9 July 2014

- Published3 December 2013