Why is Pope Francis going to Lesbos?

- Published

Papal travel is a complex science: a delicate formula that has to balance Vatican diplomatic relations, religious occasions, strategies to reach the world's 1.2 billon Catholics - and the incumbent Pope's personal wishes.

Pope Francis' trip this weekend to the Greek island of Lesbos, which hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants have used as a stepping stone in their trip to northern Europe, clearly emerges from the Pope's own personal desire.

Migrants and refugees have always occupied a central part of his discourse - and so has his criticism of the way developed countries have dealt with this crisis.

"All too often," he said recently of migrants, "[they] meet along the way with death or, in any event, rejection by those who could offer them welcome and assistance."

Hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants have arrived on Lesbos

In two speeches - at the Moira refugee centre and at the Mytilene port - Pope Francis is set to urge leaders and societies to show more compassion for those fleeing war and poverty.

But more than anything, the short visit is seen as hugely symbolic - and if you look at Pope Francis' travel record, it seems that for him, making an appearance is enough of a message.

Media power

In July 2013, his first trip outside Rome after being elected pontiff was to Lampedusa, the tiny Italian island off the coast of Libya that - like Lesbos - was becoming a symbol of the incipient migrant crisis.

Pope Francis has visited migrant hotspots before

The visit occurred months before the attention of the world turned to the deadly crossing between Libya and Italy.

Ever since then, it became clear that travelling to the front line of a conflict would become a recurring feature of Pope Francis' travel agenda.

And it has also become obvious that the Vatican is increasingly aware of the symbolic power that the Pope has - and the global media attention that comes with a visit by one of the world's most popular leaders.

So the Pope is also using his seemingly unrivalled media power to shed light on certain conflicts around the world - even if this means pushing the boundaries on the definition of papal travel.

War zones

Take his trip last November to the Central African Republic (CAR), one of the poorest countries in the world, ravaged by more than three years of armed conflict between Christians and Muslims.

For months after the Vatican first announced the trip, observers insisted that it posed too high a security risk for the Pope himself and the crowds that were expected to greet him in Bangui.

After all, never before had a pope visited an active war zone.

The Pope said he came to CAR "as a pilgrim of peace and an apostle of hope"

Pope Francis, oblivious to calls to reconsider, went ahead with the trip - visiting a mosque and camp for displaced people, holding a mass at the cathedral and calling on factions to lay down their weapons.

After the papal plane left the conflict has continued, but the visit did bring an enormous amount of media coverage to a conflict that ranks amongst the most under-reported war of our times.

It was the "Francis effect", in full form.

Message to mobsters

In 2014, moved by news of the savage murder by the mafia of a three-year-old child in the southern Italian region of Calabria, he travelled to the remote village of Cassano allo Ionio.

At the stronghold of the local crime syndicate known as 'Ndrangheta, the Pope issued a strong message to mobsters: you are all excommunicated. And his words reverberated across the Italian peninsula, where the mafia continues to expand its tentacles.

Pope Francis took a moment to pray at the US-Mexico border

Full of standout moments too was his presence at the fence between Mexico and the United States earlier this year, or his visit to Cuba in September last year, where he supported the historic thawing of the island's relationship with the United States.

But is there anything more than pure symbolism in the Pope's travels?

Awkward moments?

Sometimes his attempts to mediate in international conflicts are seen as naive, if not somewhat clumsy.

During his trip to the Holy Land in May 2014, at the end of a mass at Bethlehem's Manger Square, he broke the news that he was inviting the then Israeli President Shimon Peres and Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas to a "day of prayer" at the Vatican.

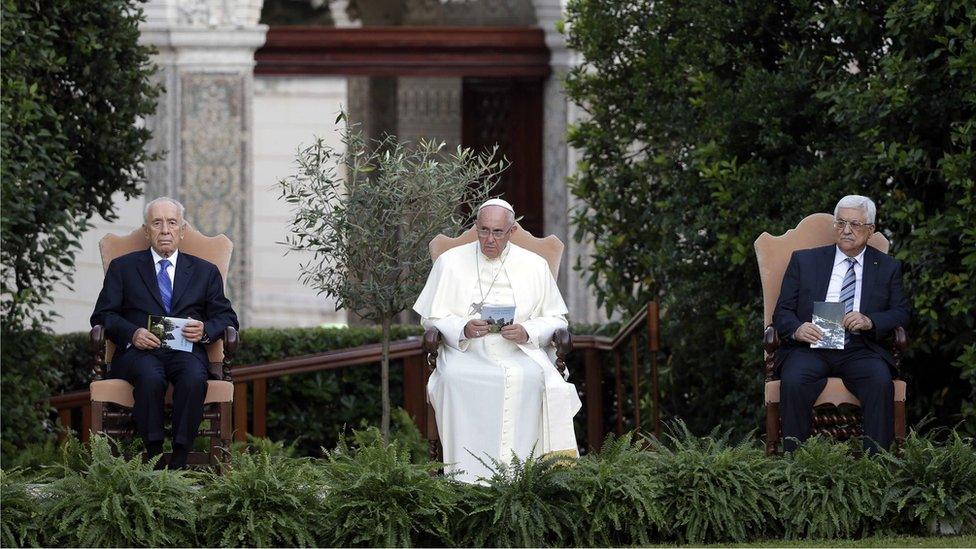

A few weeks later, the event did take place and under the eye of the world's media the three leaders - joined by the Patriarch of Constantinople Bartholomew - shared a slightly awkward photo opportunity, during which they planted an olive tree in the Vatican Gardens.

Uncomfortable pose? The then Israeli President Shimon Peres, Pope Francis and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas pictured in 2014

It is difficult to establish what concrete, on-the-ground effect - if any - such a gesture had on the decades-long conflict in the Middle East.

But, ignoring the sceptics, this Pope seems keen to continue his policy of getting involved in continuing crises - visiting hotspots in what he calls the "peripheries" of the world and issuing strong calls for more mercy for the downtrodden.

This weekend's trip to Lesbos is clearly emblematic of this approach.

Pope Francis

Born Jorge Mario Bergoglio on 17 December 1936 in Buenos Aires, of Italian descent

Ordained as a Jesuit in 1969

Studied in Argentina, Chile and Germany

Became Cardinal of Buenos Aires in 1998

Seen as orthodox on sexual matters but strong on social justice

First Latin American and first Jesuit to become Pope, the 266th to lead the Church

Said to be a football fan, supporting Buenos Aires team San Lorenzo de Almagro

- Published7 April 2016