How Chernobyl shook the USSR

- Published

The Soviet authorities' handling of the Chernobyl disaster came to symbolise a corrupt and failing system

The disaster at Chernobyl three decades ago came at a time when the rigid foundations of the Soviet system began to be challenged at various levels.

First, there was the new Soviet leader who, as the joke had it at the time, was the first in a long time who could walk and talk unaided.

Mikhail Gorbachev had been in power for little over a year. He shook not just the geriatric hierarchy of the Communist Party but also allowed, even encouraged, debate about subjects that previously had been taboo. The economy, pluralism of thought and the environment were top of the agenda.

Little did he know that Chernobyl would take the debate and public activism to a completely new level.

Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev (third from right) with wife Raisa on their first visit to the Chernobyl plant, three years after the disaster - which ultimately undermined public faith that the Soviet system could be reformed

All of a sudden the USSR witnessed a new phenomenon - the grassroots, green movement. In Ukraine and Belarus in particular, the countries most affected by Chernobyl, these movements were gaining strength at an unprecedented pace.

They were led not by party bureaucrats but by writers, students, doctors and scientists. And the Communist Party found itself in the glare of harsh, critical scrutiny.

People could not forgive the authorities for their deceit about the levels of radiation, confusing health advice and their political callousness.

A classic example was their refusal to cancel the May Day rally in Kiev and their demand that children be brought into the streets to show that Kiev was safe.

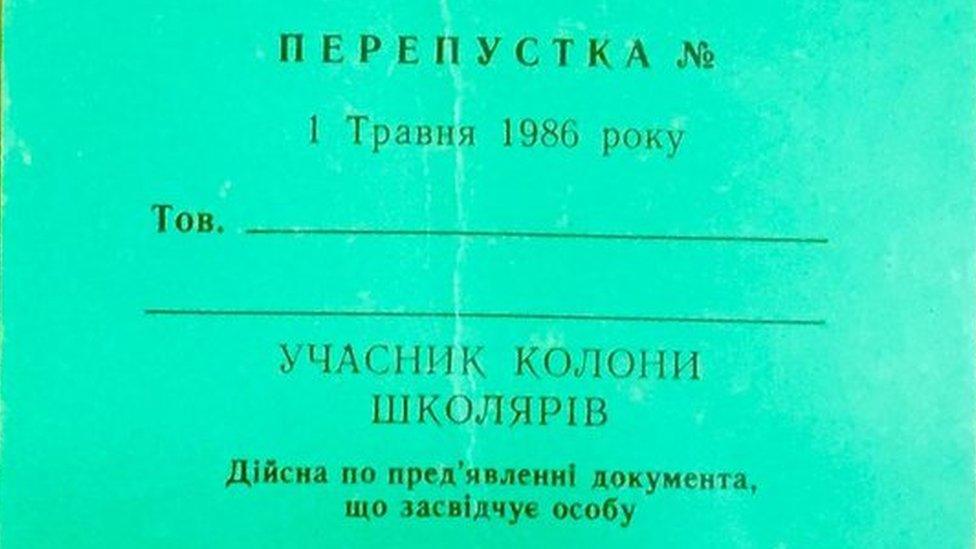

A ticket inviting a "column of schoolchildren" to join an outdoor May Day parade just days after the accident - though children of the Party elite had been flown out

When people later learned that some of the children of the party elite had been flown out of Kiev, they were devastated.

Failing system

Rallies in Ukraine organised by the green groups gathered tens of thousands of protesters.

Slowly but surely their slogans started to change, as Chernobyl revealed itself as the symptom of a corrupt and failing system rather than a technological catastrophe.

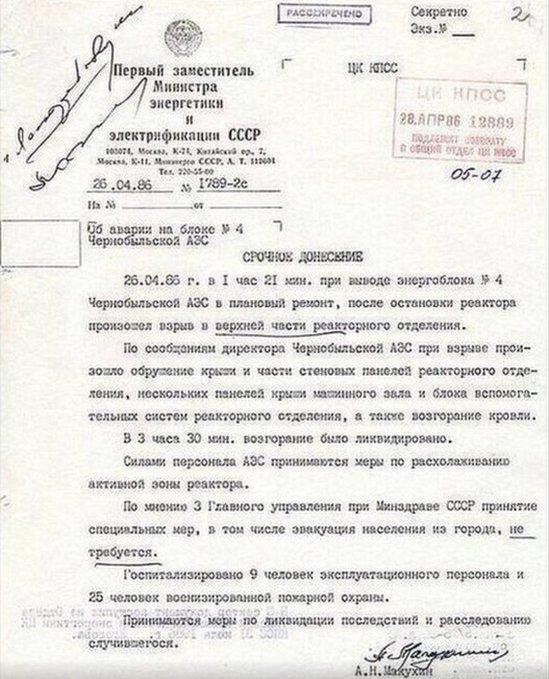

Within hours of the disaster, Soviet deputy energy minister Alexei Makukhin wrote a secret message to the Soviet Communist Party detailing an explosion in the upper part of the reactor, the collapse of the walls and part of the roof. Staff were taking measures to cool the "active zone" of the reactor, he said, adding there was no need for the evacuation of the nearby town of Pripyat.

Very soon a pro-independence movement grew on the back of the Chernobyl protests in Ukraine and Belarus - with the ineffectiveness of the Soviet system a key factor.

There was also the issue of money. The ongoing intervention in Afghanistan and catastrophic failures of the planned economy which had resulted in severe shortages of basic food staples even in Ukraine - the USSR's breadbasket - were already exerting a severe strain on the system.

Add the enormous cost of Chernobyl, and it foreshadowed a bad end to the reformist ambitions of President Gorbachev.

He and his allies tried to modernise something that was unstable and inefficient.

After Chernobyl, his own citizens did not believe it was possible. The risks were too high.

- Published26 April 2016

- Published23 April 2016