Migrant crisis: Afghan teens build new lives in Germany

- Published

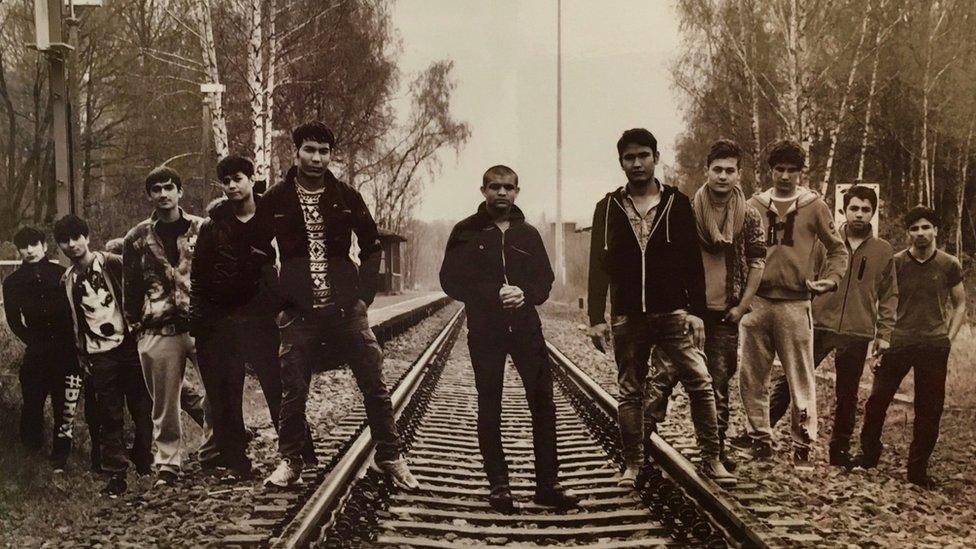

These Afghan boys are living in a home for unaccompanied migrant children in rural Saxony (pic: Detlef Rohde)

As they made their epic, sometimes harrowing journeys across Asia and Europe, the Afghan boys could hardly have imagined anything more incongruous.

On a placid stretch of the Mulde River, in the heart of rural eastern Germany, they are learning the art of rowing.

Their efforts are still a little clumsy, and their language skills rudimentary, but as they splash their way upstream, the smiles tell their own story.

These unaccompanied boys, thousands of miles from home and separated from parents and siblings, seem happy, even settled.

They are part of a huge, continent-wide phenomenon.

Young refugees near Colditz have access to education and sports such as rowing

Aid agencies estimate there are at least 20,000 unaccompanied child refugees across Europe. The real number could be much higher.

In Germany, in January and February this year, 31% of the 120,000 asylum applications were from minors, according to Save The Children.

For all their teenage bravado, these are among Europe's most vulnerable refugees.

"I don't know when I'll go back to Afghanistan," says 14-year-old Hajitullah, whose diminutive stature has already secured his place as cox.

"This is the first time I feel safe," says 16-year-old Kheshraw.

Afghan and Syrian refugees started arriving at the Paul Guenther school in Geithain in February. The school had very little notice and has had to make rapid adjustments.

German as a foreign language is now taught to a class of refugees, accompanied and unaccompanied, from Afghanistan and Syria.

Their teacher, Thomas Saalfeld, a translator by profession, has only been teaching since February. His immediate task is to get the students fluent enough to start attending other classes in German.

It is a real challenge, but Mr Saalfeld seems undaunted and his students are making obvious progress.

He says they are like sponges, with extraordinary levels of motivation.

'Like a father'

Hajitullah is just glad to be there.

"I want to get an education because in Afghanistan I never went to school," he tells me.

As he juggles with a class of different ages, backgrounds and abilities, Mr Saalfeld says he is determined to give the new arrivals the best possible start.

"They see me as a bit like a father," he says of his unaccompanied students.

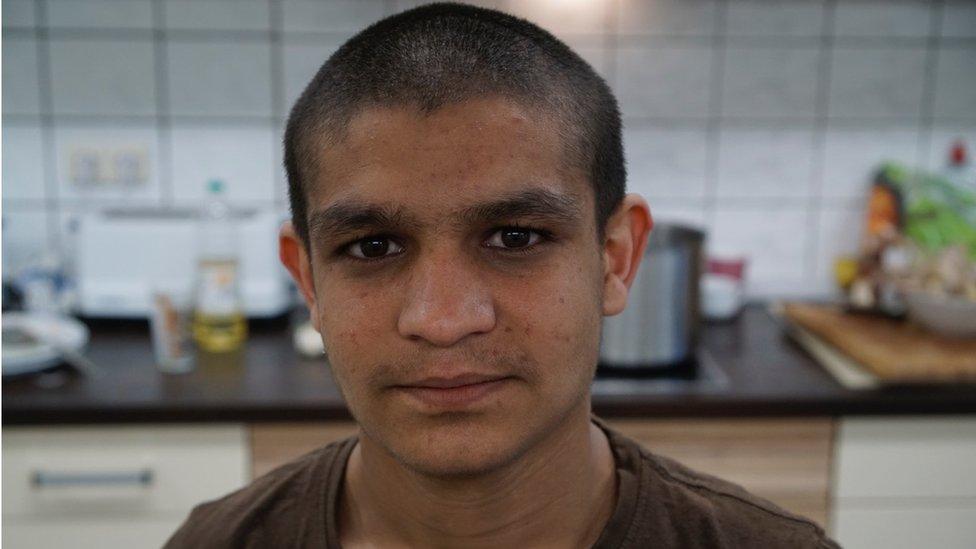

Hajitullah is just 14 and arrived in Germany alone last year

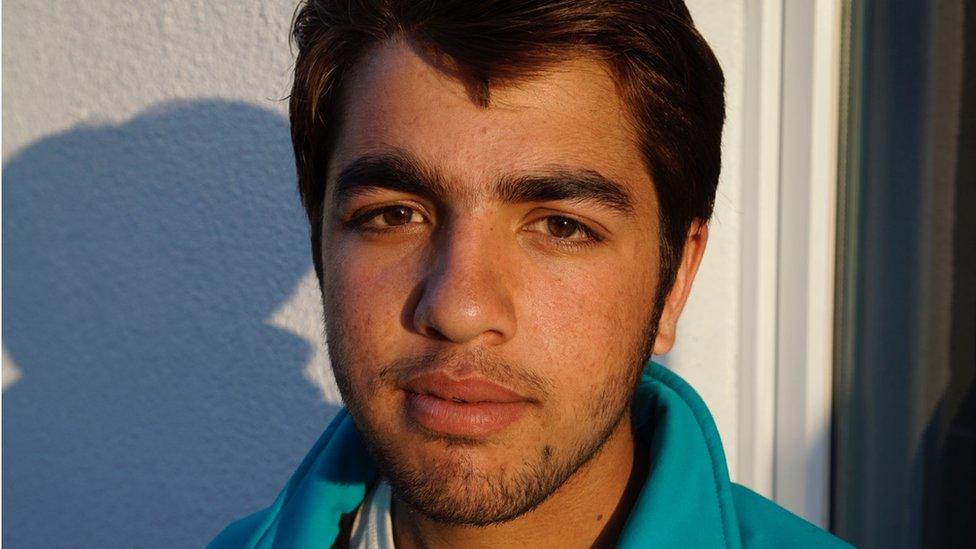

Shahid is worried about his father in Afghanistan, who was taken by the Taliban two weeks ago, he says

At break time, the new arrivals keep mostly to themselves. They have only been here a few weeks, and this small, tight-knit rural community has never had to handle an influx like this before. In nearby big cities, like Leipzig, there is anti-immigrant sentiment.

Laura Schloesser, 16, says she has not had much to do with the refugees so far, but cannot see why anyone would harbour bad feelings towards them.

"Refugees are coming not because they think Germany is such a good country. They're coming because of war and crisis," she says. "We have to respect this."

Tiny Geithain, with its ageing population and traditional values, seems to have offered a warm welcome to the refugees. But that does not mean everyone agrees with Chancellor Angela Merkel's policy of welcoming migrants with open arms.

"It's not right," says Klaus-Dieter Augustin, who runs a small shoe shop with his wife.

"No country in the world just opens up the borders and lets 100,000 people march in completely uncontrolled."

Geithain is a small community in eastern Germany

At the end of the school day, on a warm spring morning, the Afghan boys sat on the grass and played cards, listening to music from home and occasionally slipping off to make internet calls to family members.

They are free to go into town, but their €10 (£8; $11) a week pocket money from the local authorities does not go far (the home receives another €7 a week per boy to pay for cultural events).

Detlef Rohde, who put his job in journalism on hold in December to come and look after the boys, says the state should be more generous.

"We can help these people. We should help these people. We're rich enough to do that," he says.

Like the school in Geithain, he had just a few days to prepare for his new role. As for training, he says his only qualification is that he has children himself.

He is full of praise for Chancellor Merkel.

"When she said, 'I help these refugees', she did a political suicide," he says.

"I said, 'This is my chancellor'. She's right, this woman. Absolutely!"

For now, the Afghan boys are safe, being well looked after and, slowly, integrated into this quiet corner of Germany.