Europe's migrant story enters new phase

- Published

For now, the 'migrant crisis' in northern Europe is over

Refugees arriving at Rosenheim station in January - at that time the trains were coming twice an hour but now, only 80 people arrive per day

That doesn't mean there aren't people suffering nor that millions have stopped wanting to head up from Africa and the Middle East. What it does mean is that the stunning flow of more than one million people through the eastern Mediterranean, northwards via the Balkans to EU countries that we saw last year has been stopped.

Even as late as January this year, the numbers looked set to exceed last year's total with 3,500 to 4,000 asylum seekers a day still arriving in Germany. But figures obtained by the BBC show that in April a daily average of only 183 made it (giving a total for the whole month of 5,485, less than one day's arrivals back in September).

Filming at the station in the Bavarian town of Rosenheim in January, we were told that 800-1,200 migrants were arriving every day on trains from Austria.

Last week, a federal police spokesman in Rosenheim told us that the daily average is now only 80, almost all of whom have come via the "Brenner route", meaning Austria's border with Italy. Even this, though, is now being sealed by the Austrian government, amid scenes of protest at the weekend.

Other countries that took large numbers of asylum seekers last year - from Hungary to Austria, the Netherlands or Sweden - all report similarly dramatic reductions.

International co-operation works - and so do fences

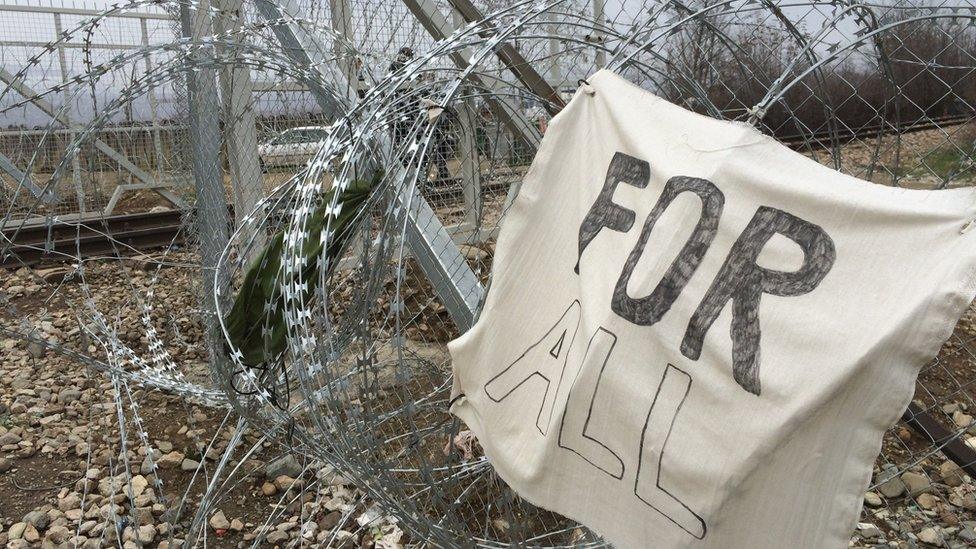

A fence at the Greece-Macedonia border, seen from the side of Idomeni, Greece

There have been two major elements to the effort against illegal immigration. The first is the European Union's deal with Turkey, external. In return for billions of euros, a promise of visa-free travel and a new legitimate scheme for resettling people who have fled Syria, Turkey agreed to clamp down on the people smugglers as well as accepting migrants caught and deported from Greece.

The deal with Turkey has been controversial, not least because many Europeans feel it conceded too much. It is also fragile. Last week Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan threatened to scrap the whole arrangement because of a dispute with the EU over his country's tough anti-terror laws.

Turkey's deal with the EU has had a dramatic effect, but it hasn't been 100% effective. Last week, for example, 537 migrants arrived in Greece from Turkey.

Efforts to prevent people going further north have, however, been completely successful - or as near to that as matters. And this brings us to the sealing off with razor-wire fences of the Greek-Macedonian frontier as well as successive border crossing points on the migrant route through the Balkans.

This centre for migrants in Slovenia is now empty

Filming at the transit centre at Sentilj in Slovenia, close to the Austrian border, in mid-April, relief workers told me that not a single person had arrived since Macedonia closed its border with Greece in early March. The camp, which at its peak processed 4,000 people in a day, is now being gradually dismantled.

The action between a group of Balkan states, co-ordinated by Austria, to close off these routes faces its own uncertainties - not least that the Macedonian government is tottering in the face of a domestic political crisis.

But the conclusion that many have drawn - particularly nationalist politicians in Austria and Hungary - is that fences work and could be used to protect Europe's borders even if President Erdogan reneged on his deal with the EU.

Southern Europe remains exposed

Thousands of migrants are still arriving in Italy by sea

Many predicted that closing down the Greek route would drive many to cross the Mediterranean from Libya. In truth though it's not that simple, because of the risks, both in the sea crossing and from brutal Libyan militias.

In 2016 so far, around 29,000 have arrived in Italy and they continue to do so at the rate of roughly 1,500 a week - that's about one-fifth to one-sixth of the traffic that was going via Greece before the EU-Turkey deal came into effect.

Just as last summer's mass migration prompted the sealing off of Greece by its northern neighbours so this is happening now with Italy, led once more by Austria but with Switzerland and France also restricting freedoms previously granted by the Schengen agreement.

The danger for both Greece and Italy is that their European "partners" fail to honour pledges to resettle those given asylum, seal off their countries and that arrivals across the Mediterranean continue. With more than 50,000 already stranded in Greece, this scenario is already very real to them.

The underlying causes remain

Most of the migrants who arrive in Italy have come from West Africa

Last week, the International Institute for Strategic Studies reported that the number of people displaced by armed conflict (mainly in the Middle East and Africa) had increased by 40% since 2013.

Add to that an often desperate search for opportunity. Most of those coming across the Italian route are not Syrian or Iraqi but from Nigeria, The Gambia, Senegal and Guinea.

Among Syrian and Iraqi asylum seekers, one phrase commonly heard on the migration route north was "Europe invited us" or "Merkel invited us".

How far the marked change of attitude in Europe changes this feeling we will soon see. But a growing sense of the difficulties of making the journey, as well as of the hardships that could await, may well reduce Europe's pull factor, particularly for those coming from the Middle East.

Fortress Europe is here to stay

Fortress Europe is closing its borders

The shutting down of the Balkan migration route may well have saved Angela Merkel's chancellorship. Success will lead many to doubt the formula that mass migration into Europe is just a part of globalism that cannot be resisted, not least because anti-immigration politics is surging across the continent.

Such is the desire of European politicians to "regain control over the EU's external borders", to use Mrs Merkel's favoured phrase, that they will make extraordinary bargains with Turkey or indeed Libyan militias.

And while many have commented that President Erdogan now has a pressure point he can use against the EU at will, that also gives him an interest in the deal's continued survival.

What the last few months have shown us is that many governments (notably in central and eastern Europe) are far more interested in preventing illegal migration than they are in living up to refugee quotas. Some have also made clear that they are prepared to use their armed forces to protect their borders if they have to.