Protecting Europe from ballistic missiles

- Published

The defence facility can now 'fire bullets at bullets'

America's latest addition to its Ballistic Missile Defence System looks out of place surrounded by mile after mile of flat Romanian farmland.

The building at Devesulu,, external which houses radar and 12 interceptor missile tubes, appears remarkably similar to the "sensors and shooters" that have already been placed on US Aegis warships.

It has even been painted in the same battleship grey and is manned and operated by US Navy personnel who will rotate on six-month tours as if they were at sea. They might as well be, because there are few signs of human life nearby.

Devesulu is the first land-based ballistic interceptor system to be set up in Europe. At a ceremony attended by Romanian, US and Nato leaders on Thursday it was declared "operational".

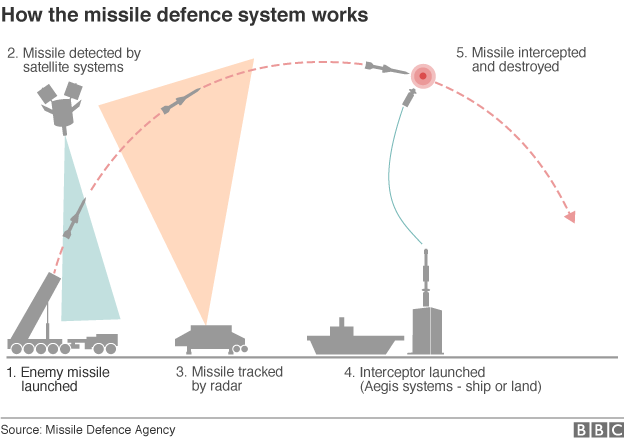

It is now able to fire "a bullet at a bullet": the interceptor missile tries to hit a ballistic missile on re-entry into the earth's atmosphere.

Work is now starting on building a second base in northern Poland. Together with four US Aegis warships, these Aegis Ashore sites will provide a network that can identify, track and shoot down ballistic missiles fired towards Europe.

Turkey already has an early warning radar that activates the Aegis system and will eventually be joined by one in the UK.

Dutch and Danish warships are also being fitted with sensors that will plug into the system.

It will all be controlled from the US base in Ramstein, Germany. Ostensibly under Nato control, in reality it is the US that is largely driving and funding this programme.

Where is the threat?

So where does the threat come from? Nato's Secretary General, Jens Stoltenberg, says "many countries are seeking to develop or acquire their own ballistic missiles".

The Middle East region is often mentioned but US officials have been more specific in naming Iran as a potential aggressor.

Despite the recent agreement on Tehran's nuclear programme, it is pressing ahead with its own ballistic missile programme.

Still, it seems odd to ramp up the pressure on Iran so soon after it's made concessions to the West. As for other "threats from the Middle East" it is all rather vague.

Strangely, the clearest language from both Nato and US officials is about what the system is not. "It's not about Russia" is the prefix to any description of the system.

At the Deveselu ceremony the US Deputy Defence Secretary, Robert Work, said: "I want to make clear - neither this site, nor the site going into Poland - will have the capacity to undermine Russia's strategic (nuclear) deterrent."

Mr Stoltenberg insisted: "The interceptors are too few and located too far south to intercept Russian intercontinental ballistic missiles."

The base is staffed by US personnel

The language, though, appears to be deliberately precise. There is no mention of Russian short and medium range ballistic missiles.

Nor is there any denial that the sensors will be able to look into Russian territory. Few would argue the two nations housing the land-based interceptors, Romania and Poland, are more worried about say Iran or North Korea's actions than their biggest and nearest neighbour.

There are, of course, plenty of good reasons to play down any potential impact on Russia as tensions are already high.

Russia has been flexing its military muscle near to Nato's borders and the Alliance has responded by stepping up its own military exercises.

It is easy to see why the reassurances have not worked.

Moscow says the system is a threat to its own security, even if it is a defensive measure. And given recent history it is hard to see how this system, which will be upgraded through its lifetime, has "nothing to do with Russia''.

Russia has a track record of being misleading and worse - not least over its intervention in both Ukraine and Syria.

But on missile defence, Nato and the US may also risk being accused of not telling the whole truth.

- Published12 May 2016

- Published11 May 2016

- Published3 May 2016

- Published28 October 2013

- Published20 May 2012

- Published3 May 2012