Migrant tragedy: Anatomy of a shipwreck

- Published

The stretch of the Mediterranean between Libya and Italy has claimed thousands of migrants' lives

An unprecedented operation by the Italian Navy is under way off the coast of Libya to recover the wreck of a migrant boat that sank in April last year - leading to the deaths of up to 700 migrants, the largest single loss of life in the Mediterranean in decades.

Only 28 people survived the sinking on the night of 18 April - among them, a 27 year old Tunisian man who is currently facing trial in the Sicilian port town of Catania, accused by prosecutors of being the skipper of the migrant boat and part of a network of Libyan smugglers.

Mohammed Ali Malek faces charges of multiple manslaughter, human trafficking and irresponsible sailing of the boat. Prosecutors have asked for an 18-year jail sentence.

Mohammed Ali Malek (left) was among the 28 survivors in the shipwreck which claimed up to 700 lives

In an exchange of letters with BBC News from his jail in Catania, Mohammed Ali Malek claims that he is innocent, not the captain but just another migrant who paid 2,250 Libyan dinars ($1,600) to get on the boat that would take him to Italy, where he had lived in the past.

But court documents show that all the other survivors - including a Syrian man also under arrest and accused of being second-in-command - told officials that not only was Mohammed Ali Malek captain of the boat, but that his lack of sailing skills had caused the tragic collision with a Portuguese ship that had come to its rescue.

Few concrete details are known about the exact dynamics of the accident - so what do we know now about how this overcrowded migrant boat ended up in the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea?

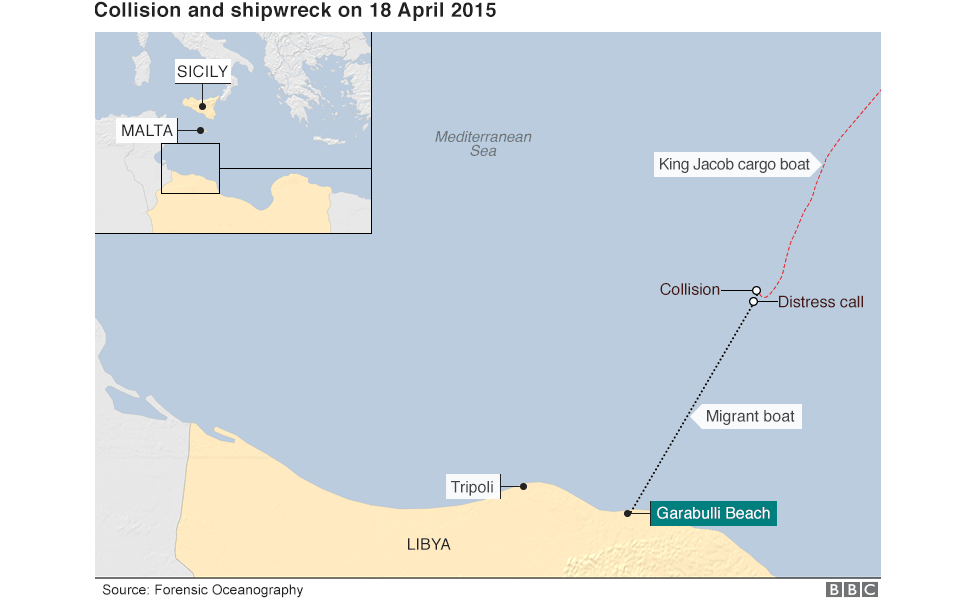

The boat's journey started, like so many others, on the beaches near Garabulli, in Libya.

Many migrants who try to make the crossing from Libya set off in inflatable boats before joining larger vessels. off-shore. This boat has been intercepted by Libyan authorities

The migrants, most of them sub-Saharan Africans fleeing from poverty and conflict in their home countries and further violence in Libya, were being held at an illegal centre near the coast.

From there they were taken in small groups by dinghy to a wooden fishing boat anchored off the coast, where they amassed on the deck and inside the hull.

The 27m-long (90ft) boat is thought to have been carrying more than 800 migrants.

Mohammed Ali Malek was one of those operating the dinghies, survivors told Italian prosecutors. As soon as the fishing boat was packed with migrants, he took the helm and brandished a wooden stick to coerce migrants to follow his orders, they said.

Distress call

The boat set off at the crack of dawn on 18 April.

According to the survivors, it quickly became evident that he had little experience commanding a boat. They claim he did not know how to read a compass and that he asked for help from the migrants huddled on the deck.

Hasan Ksan, a Bangladeshi survivor, said that the captain had used a satellite phone several times to communicate with his colleagues back onshore in Libya - and that he was armed with a gun.

The boat continued its journey for several hours - and by mid-afternoon, the captain of the boat followed what by now is the regular procedure for migrant boats making the long crossing.

Once in international waters, he placed a distress call with the Italian coast guard in Rome and asked for rescue.

Abdullah Ambrousi was the commander of the King Jacob, an enormous Portuguese container ship that was sailing nearby.

He received a call from the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre in Rome, asking him to change course and attend to the fishing boat in distress.

He did, and after around two hours, the radar on his ship detected the presence of a vessel in its vicinity. But it was so small, and it was so dark, that it was impossible to see anything with the naked eye.

The King Jacob started heading towards the signal and Capt Ambrousi ordered his crew to switch on one of boat's headlights.

Now he could see it - a wooden, rickety and extremely overcrowded fishing boat.

Inside the hull of the boat was Ousmane Gano, a 31-year old migrant from Senegal.

The migrants on the upper deck of the vessel told those amassed inside that they could see "a big ship" that had come to their rescue, he explained.

"They asked us not to move to keep the boat stable."

Sank within minutes

Capt Ambrousi told Italian investigators that he steered the King Jacob to avoid collision, but that whoever was sailing the migrant boat continued to do so erratically, as if trying to "follow" the King Jacob's sudden change of route.

He then insists that he ordered his crew to switch off the King Jacob's engines to avoid a collision.

But from the bridge, he saw tragedy unfolding before his eyes.

The fishing boat started to sail at slow speed towards the King Jacob - but then, Capt Ambrousi said, it suddenly increased its pace.

The small vessel's bow rammed the King Jacob's port side, and then its starboard side scratched against the huge merchant ship.

The King Jacob cargo ship responded to the call for help

The fishing boat manoeuvred as if sailing backwards - but started to lose balance possibly because of the agitation among the panicked migrants who could see what was happening.

It started to capsize, and in less than five minutes, Capt Ambrousi told investigators, the fishing vessel had sunk.

Mohammed Ali Malek's timeline of the events that night is not entirely different from what other survivors narrate - but in his account, the "role" of captain is played by "an African man" he cannot identify because "he maybe died in the sinking".

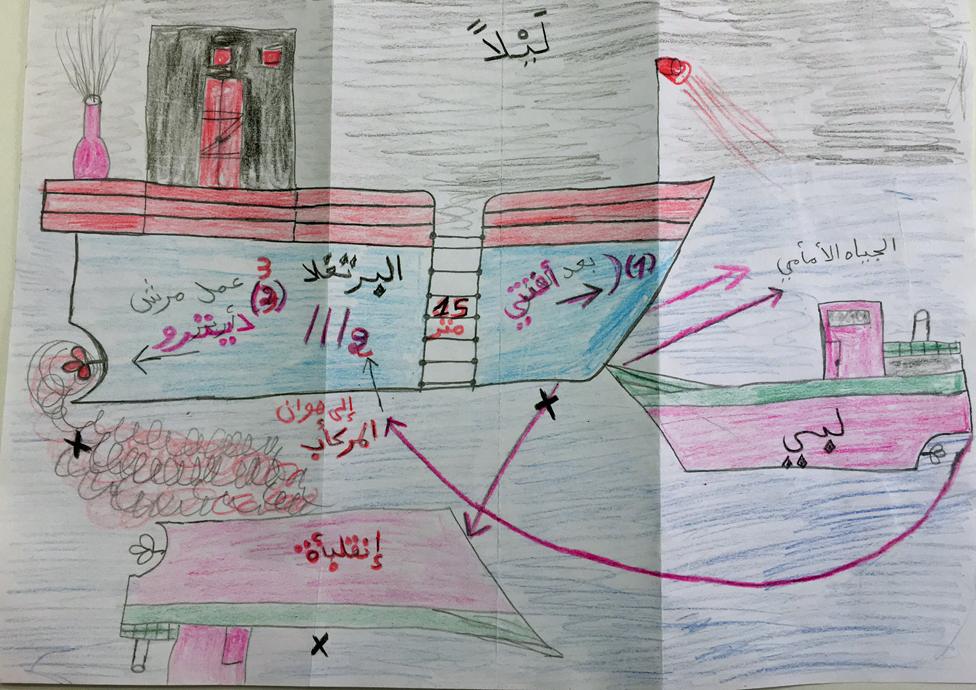

He admits in his letters that the two vessels crashed into each other, although in his account it was the King Jacob that hit the small boat.

And he alleges that the migrant boat lost balance because "the big blades of the propeller [of the King Jacob] created big waves that capsized our ship and we all fell into the sea".

Mohammed Ali Malek's drawing of how the collision happened

Mohammed Ali Malek sent BBC News a drawing showing his version of how events unfolded - but prosecutors in Catania have no doubt that he is to blame for the crash.

His "naive, careless and negligent" sailing of the migrant boat caused the collision, reads his formal accusation, which highlights that the accounts of the crew of the King Jacob and the survivors match almost completely, and that the marks left on the King Jacob's port side also confirm this account.

Mr Malek and his lawyer, Massimo Ferrante, made a formal request to include the recordings of the King Jacob's black box as evidence in the trial - the tribunal refused their request, mainly because the recording had been erased with time.

Survivors, including Mr Malek, describe the complete chaos that followed the capsizing of the ship.

In his letter, he told BBC News how he climbed on to fishing nets and described the scene.

"From there I could see many people at sea, shouting for Allah, who sadly then died", he wrote.

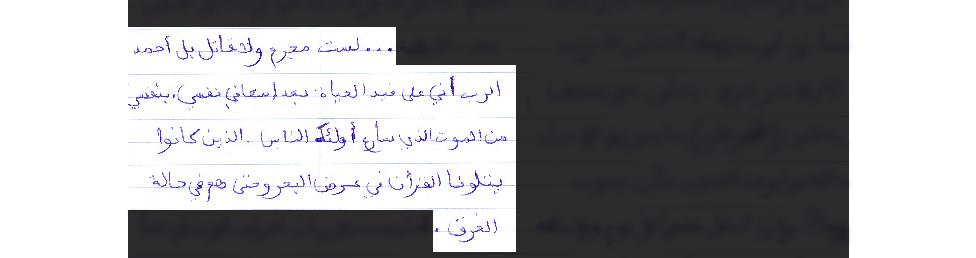

One of Mr Malek's letters to the BBC

"I'm neither a criminal nor a murderer. I thank God that I'm alive after saving myself from death which many people on the boat faced and started reciting the Koran as they were drowning"

Letter from Catania prison, May 2016

Mohammed Ali Malek faces charges of multiple manslaughter, human trafficking and irresponsible sailing of the boat

Interviewed by UK-based research group Forensic Oceanography, a Sierra Leonean survivor told how, once he was safe on the deck of the King Jacob, he could see his friends swimming for their lives, trying to hold on to ropes that had been thrown to save them.

An Italian Coast Guard vessel and several other commercial ships rerouted to the scene joined the recovery effort - but only 28 people were saved.

The number of dead is still uncertain - so far, 171 bodies have been recovered.

Italian authorities fear that, once the wreck of the boat has been examined at port, the total death toll from the event could reach up to 700.

The migrants' boat lies at a depth of 370m. It is thought hundreds of bodies may be on board

Meanwhile, Mohammed Ali Malek awaits the next hearing of his trial in Catania.

"To the relatives of the victims I would say that all the accusations against me are influenced by the statements from the other survivors," he wrote in one of his letters.

He insisted that he had been accused because he was the only Tunisian on board, and that his alleged deputy Mahmud Bikhit, who is also on trial, was unfairly accusing him of being the captain.

"I'm neither a criminal nor a murderer," wrote Mohammed Ali Malek. "I thank God that I'm alive after saving myself from death which many people on the boat faced and started reciting the Quran as they were drowning."

The sinking came a few months after the Mare Nostrum search and rescue operation was suspended

Many believe that the criminal charges against him are only a part of the picture when trying to understand how such a massive loss of life could happen in the Mediterranean.

In their report Death by Rescue, external, researchers Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani claim that the lack of a proper search and rescue operation off the coast of Libya put lives an peril - and was a crucial factor in determining the fate of the migrant boat.

A few months before the accident, Italy had suspended Mare Nostrum, its wide-ranging operation in the stretch of sea between Sicily and North Africa. Operation Triton, managed by the EU's border agency Frontex, replaced it.

Triton's area of coverage was much more limited in scope, which meant that commercial ships travelling in the area - like the King Jacob - were called upon more often to assist migrant boats in trouble.

These merchant ships, the researchers write, were "unfit to carry out the large-scale and particularly dangerous rescue operations involving migrants", and that the burden on them was "excessive".

Migrant shipwrecks Jan 2014 - April 2016

The April 2015 sinking, together with another one a few days earlier which left a smaller number of victims, marked a turning point in the EU's management of the migrant crisis.

The reach of search and rescue operations was extended, while a separate mission was launched to fight smugglers at sea, with mixed results.

Meanwhile, relatives of the hundreds who died that April night will find consolation in the fact that they finally may be able to bury their loved ones, thanks to Italian efforts to identify all bodies.

When announcing the plan last year, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi said that these people were pursuing "freedom", and giving them a proper burial was a gesture of "humanity".

Web production by Christine Jeavans

- Published19 April 2015

- Published20 April 2015