Inside Cizre: Where Turkish forces stand accused of Kurdish killings

- Published

Parts of Cizre were levelled after forces left

Serious allegations have been made about the deaths of civilians at the hands of Turkish security forces in the overwhelmingly Kurdish town of Cizre in south-eastern Turkey earlier this year.

Local people say Turkish security forces killed up to 160 civilians in the town, according to statements made to the BBC and human rights groups.

The worst single incident ended with the deaths of around 100 people who had been sheltering in three cellars.

The UN human rights chief has expressed his concern in unusually strong terms and wants to send in investigators.

The Turkish foreign ministry dismissed the allegations. It said that the Turkish military took all necessary precautions to protect civilians during military operations.

The killings happened during a 78-day curfew imposed on Cizre between 14 December 2015 and 2 March this year. During the curfew, the town of about 100,000 people was sealed off.

The curfew was part of a military campaign in south-eastern Turkey, which is still going on, targeting the PKK, the armed Kurdish group. Turkey, the European Union and the United States classify it as a terrorist organisation.

Since the long-running conflict resumed last year, the PKK has killed hundreds of Turkish soldiers and police. It has also exploded bombs in Ankara, the Turkish capital, killing many civilians.

Most Turks, and some Kurds, condemn the actions of the PKK. But in the Kurdish villages and towns of south-east Turkey, the PKK is often seen as a protector.

Firat Duymak, whose father died: "In Turkey we have nothing. There is no justice; there is no court"

In Cizre, some of the most serious allegations centre on the area around Bostanci Street, where Turkish security forces are accused of killing as many as 100 civilians who were sheltering in three basements.

Until the curfew, Bostanci Street was part of a district of narrow streets and densely-populated blocks of flats. The buildings were shattered by artillery, tank fire and street fighting, according to local people. When the curfew ended and the fighting stopped, Turkish security forces sent in bulldozers to level the ruins.

Now it's hard to see where Bostanci Street ran. I am shown the site of the cellars by 18-year-old Firat Duymak, whose father, Mahmut, was killed there. All that is left is a pile of rubble, indistinguishable from the rest of the wasteland of concrete fragments that was left behind by the war and then the bulldozers.

Firat denies that his father was a member of the PKK. He says he was in the cellars to look after civilians who were there, including students who had come from elsewhere in Turkey just before the curfew was imposed to show solidarity with Cizre.

Firat condemns the actions of the Turkish state and its police and military.

"They are the terrorists; the ones who commit all these atrocities," he says. "Even if those people were from the PKK, why does the state have to destroy and burn their lives? Even war has rules.

"Can you rip the people up when you catch them? You have courts; you have a justice system. In Turkey we have nothing. There is no justice; there is no court."

The UN wants to investigate allegations that Turkish forces massacred around 100 civilians in Cizre.

'All coming from Erdogan's head'

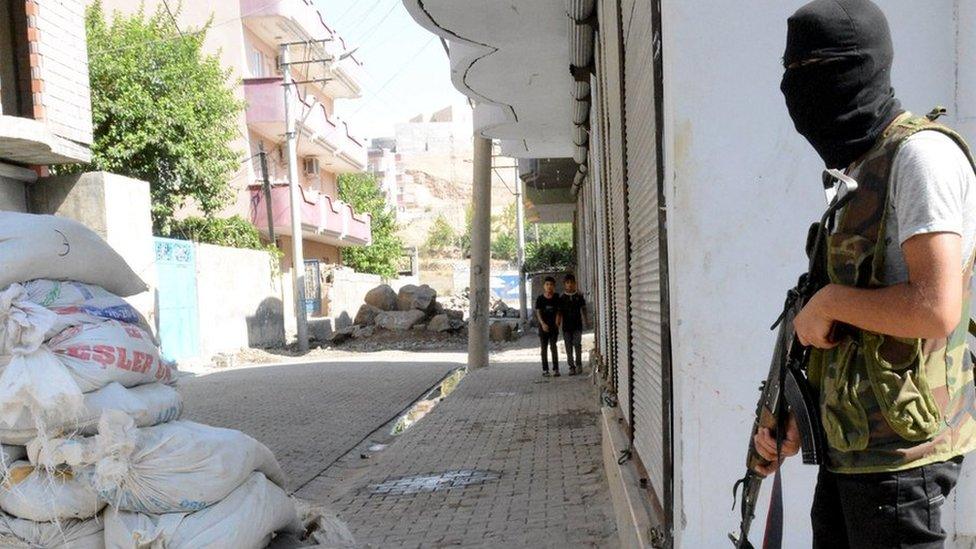

The areas of Cizre that were targeted by the Turkish military were known to be centres of PKK activity. Since 2014, a militant PKK Kurdish youth organisation had made parts of Cizre effectively a no-go area for the police, digging trenches and blocking roads.

Some local people resented what looked like preparations for war. Kurdish MPs tried to persuade the PKK militants to fill in the trenches, with limited success.

The question is whether the Turkish state's response to an outright challenge to its authority was proportionate to the threat it faced and in line with the laws of war.

Firat Duymak and many other Kurds in Cizre say it was not. He blames Turkey's President Recip Tayyip Erdogan, whose government is increasingly authoritarian, and produces his father's identity card.

"All these things are coming from Erdogan's head. My father was not a terrorist, he was a civilian; he was a citizen," he says.

"The state should look at his ID card. Let the state look at his identity. The Turkish flag is on his ID card, not the flag of the PKK."

'My kids will grow up with a grudge'

Back at the family home, where war damage is still being patched up, Firat's mother Lutfiye sits with the youngest of her five children, a boy of three.

"All my kids have been hurt psychologically," she says. "We were in the firing line for a month. You cannot sleep; you cannot go to the toilet. They call you a terrorist. They behave as if you are not a human being. No human being could do this to anybody.

"My kids will grow up with a grudge. Do you think you can finish Kurds? You cannot."

She says that soldiers smashed up homes of residents, and defecated on the beds.

"How does a person who does that claim to be a human being?"

Lawyers from the local Bar Association told investigators from Mazlumder, a Turkish human rights group, that "following the deaths in the basements in Cizre, there was no crime scene investigation and no judicial authority was allowed to enter the basements."

Mazlumder also heard allegations that civilians, including children, were targeted and shot dead by government snipers.

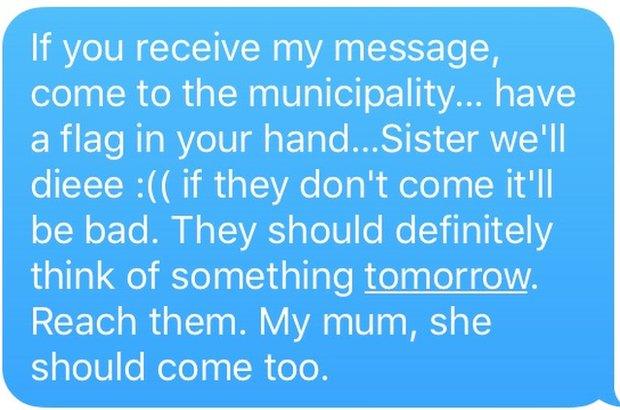

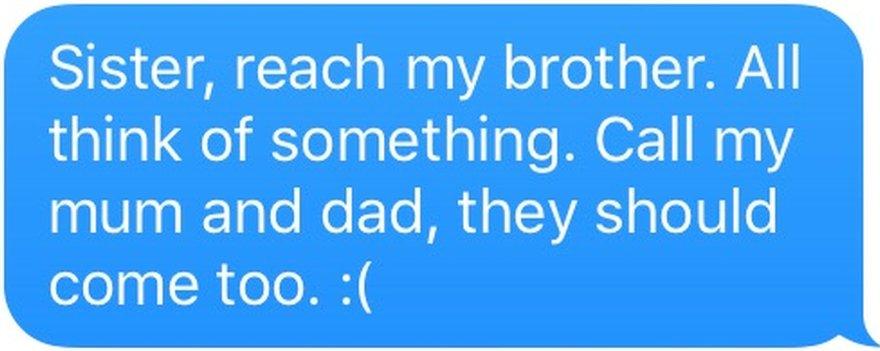

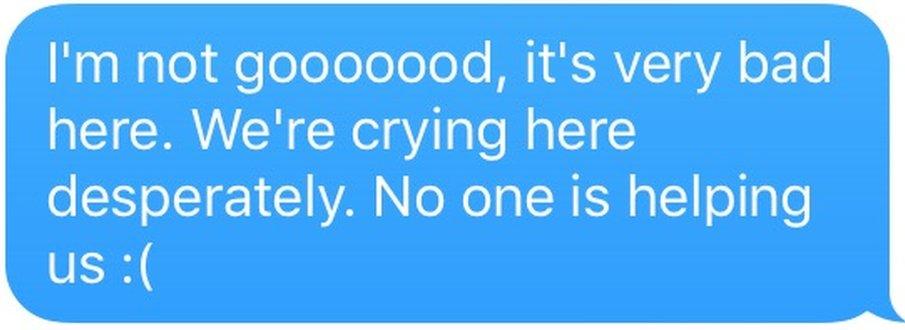

A 50-something couple, Mehmet and Murside Balcal, sit in the courtyard of a rented house - their own home was destroyed - mourning Ferhat, their 20-year-old son, who died in the cellar.

His father reads out text messages various members of the family received from their son. He had implored them to organise a demonstration to try to persuade the security forces who ringed the cellars to let them out.

(The original text messages have been translated into English.)

Murside, his mother, was turned back and she says they were arrested when they tried to demonstrate. She sits with two portraits of her son in her arms, hugging them and weeping.

But this is a bitter conflict, and the weeping is on both sides.

Pinar Saglam's hands shake as she lights a cigarette. On 13 March, a female PKK suicide bomber in central Ankara killed Kirim, her 21-year-old brother, and 36 others.

Pinar shows me a photograph she found on the web of a poster the size of a building in a Syrian Kurdish town.

It shows the leader of the PKK, Abdullah Ocalan, who is held on a Turkish prison island, next to the photograph of the woman who killed her brother and so many others.

Pinar is incredulous at the way the bomber was glorified. "Like a leader, like an angel," she says. "I mean, when I saw this picture I can't believe my eyes, because it can't be true, it can't be true.

"She was a murderer, murderer of my brother. Now her picture is displayed on the streets of Syria.

"I wrote about my feelings on Twitter. A Kurdish woman said to me that I was a Turkish Nazi. She said I shouldn't speak the way I do. She said Kurdish children are often killed in Kurdistan."

Pinar says she wants peace, not revenge. Plenty of other Kurds and Turks feel the same way.

But this is about more than a succession of personal tragedies, and the grief of parents and children.

The violence between Kurds and the Turkish state is the latest instalment of a long-running conflict. An attempt at a peace process collapsed last year. Both sides blamed each other.

The violence is not happening in a vacuum: the Middle East is gripped by violent change. War in Syria and Iraq is changing the region's balance of power.

Turkey is deeply involved in the war in Syria, backing militias fighting the regime. It is also a member of Nato. It is a big player in Europe and the Middle East.

Kurds in Syria are closely allied with the PKK, and have strengthened their position as the Assad regime retreated.

Ironically, the Syrian Kurds are also allies of the West, as they have fought well against the jihadists who call themselves Islamic State. But the Syrian Kurds' allies and patrons in the PKK are regarded as terrorists.

That adds up to a serious complication.

Turkey's President Erdogan is as worried as any of his predecessors about Kurdish ambitions for self-government. Perhaps more so, as the Kurds, despite their internal differences, have been among the winners so far in Syria and Iraq.

President Erdogan is acting to crush Kurdish ambitions, hoping that the tide will not turn in favour of Turkey's Kurds.

The European Union, meanwhile, wants Turkey to be a big part of the solution to the refugee crisis that has been created by war in Syria and Iraq.

On a pile of rubble in Cizre, next to the cellar where his father was killed along with dozens of others, is Firat Duymak. He blames the Turkish state for his father's death, and the European Union and Turkey's other allies for allowing it to happen.

"Europe blatantly watched all these atrocities, and did nothing, because of the refugees," he says.

"What Europeans do any more is not my concern. We don't need anyone's help. We're not interested in what they do or not do.

"The whole world is responsible for what happened in here."

- Published4 November 2016

- Published23 August 2016

- Published10 September 2015