Is populism a threat to Europe's economies?

- Published

Speaking to the people? Populism is on the rise in Europe - but is it a cause or effect of economic crisis?

The Financial Stability Review isn't bedtime reading for most of us, but among the 143 pages of its latest edition, a short passage of just a few lines has ruffled some feathers.

The report is published twice a year by the European Central Bank - a key institution responsible for implementing monetary policy across the continental union.

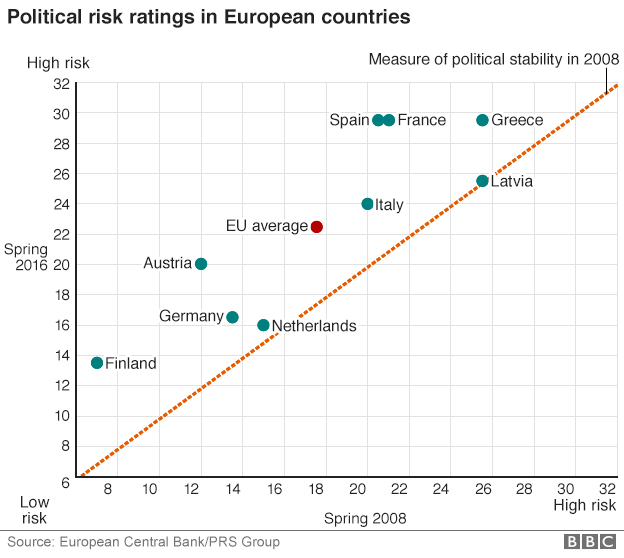

On page 12, nestled among warnings about "weak profitability expectations" and "prospective stress in the investment fund sector", is a rather starkly political message: "Political risks have increased across the euro area and pose a challenge to fiscal and structural reform implementation and, by extension, to public debt sustainability."

In other words?

The rise of populist parties across Europe, it is saying, has made the implementation of the orthodox economic reforms - espoused by the EU as a route to greater economic success and stability - less certain.

"This, in turn, may cause renewed pressure on more vulnerable sovereigns and potentially contribute to contagion and re-fragmentation in the euro area".

Re-fragmentation in the euro area? That really doesn't sound healthy for the future of the part of the bloc using the single currency. And the survival of the monetary union is indeed one of the big worries of these pillars of the European establishment.

What's the context?

The document feeds in to a broader narrative about the crisis - whereby the perceived failure of centrist or social democratic parties and the political establishment to deal with economic malaise has opened the door to upstart parties with "extreme" solutions - whether of the right or left.

From Finland to France to Hungary, the nationalist right has enjoyed recent success; and in Greece and Spain, radical left parties have gained fresh electoral appeal.

As populations ring the changes at the ballot box, European policymakers are keen to the threat that may be posed to their policy prescriptions by new parties which reject the old political and economic consensus.

Does business share these concerns?

I spoke to Christoph Schneider, a director at the federal chamber of commerce in Austria - where just days ago, the far-right Freedom Party failed by a whisker to take the presidency.

It is a largely ceremonial role but, many argue, would have been an important step for the party on the way to a more muscular political presence.

He told me that despite a "period of tension" in the run-up to the election, businesses in Austria were unsettled rather than panicked by the rise of the nationalist right.

"The Freedom Party doesn't really have a programme so we don't know what they stand for - except for their opposition to mass immigration, you can't pin them down," he said. In a previous coalition government in 2000, the party actually spearheaded a package of reforms seen as successful.

At the moment, he would describe the party as "an opportunist rather than a populist party" which is benefiting from the established political parties' failures to take popular concerns about Europe seriously.

But he said there were longer term concerns, both in the business community and the wider population.

"Until five years ago, we had economic success, political stability and social peace. Now the first two are in question - and once those falter, the third is next in line."

What about the view from the markets?

For Steve Barrow, strategist for Standard Bank, the ECB's warnings about populism has to be assessed on a country-by-country basis.

"I can see the ECB's point - but maybe it depends on what this populist force does with whatever power it might achieve."

Syriza in Greece, for instance, has "actually probably not done anything to the political orthodoxy" because it had so few options other than toe the line or exit the eurozone entirely.

"In Austria, Finland, France perhaps - you could argue that it would be different if a populist party had more power, that they're in a stronger position than Greece, not going cap in hand to the EU, in terms of doing things the EU doesn't like."

Nevertheless, for Mr Barrow, the crisis has highlighted the weakness of the European Union as much as the creditor countries.

"The EU should really be fining some countries for their budget indiscretions, but that's politically unacceptable - and part of the reason for that is that if we have traditional parties in power and they're not doing as much as the EU likes, and then the EU turns round and fines them, then you'll actually create an even bigger hotbed for the populist-type movement that rebels against what the EU is doing."

Instead, countries who are falling behind get a blind eye turned to them and more money loaned - "it's more 'extend and pretend', as economists like to call it. But potentially unsustainable debt is a problem for everyone".

The rise of the nationalist right has been mirrored by leftist parties elsewhere - such as Podemos in Spain

Has the ECB got its analysis the wrong way about?

It has, according to Olivier Vardakoulias, economist at the UK's New Economics Foundation (NEF).

"The ECB is mistaking the effect for the cause," he says - the rise of so-called populist parties is the result of economic and financial turbulence brought about by the way the crisis was handled by eurozone authorities, member states, and of course European institutions including the ECB itself.

Its response was to force member states to undertake "structural reforms" - "reactionary social measures including dismantling of the welfare state, dismantling of labour rights, reduction in social spending and so on", themselves deepening the crisis.

That in turn provoked different reactions - a pro-European far left challenging austerity and an openly anti-European far right.

In Greece and elsewhere, he says, the pro-European parties have been humiliated. "Greece was literally crushed and its democratic sovereignty was crushed" - "a reaction which was itself extreme".

"This is the danger, I think - if these movements fail to offer an alternative then I very much fear that people will turn to nationalist anti-European parties - and this will be a disaster for Europe."

What's his alternative?

Mr Vardakoulias insists that Europe needs to come to terms with the fact that its strategy has not delivered - and is putting at risk the political stability of Europe.

"The question is do they want to or are they ready to accept these facts and move towards an alternative policy for Europe as a whole - democratising the institutions, and actually resolving the crisis in the periphery but also in countries like France?

"If they don't there is a high risk that the eurozone will implode."

- Published13 November 2019

- Published1 January 2016