Switzerland basic income: Landmark vote looms

- Published

Under the plan each citizen would receive an equal monthly payment, regardless of their circumstances

Switzerland will become the first country in the world to hold a nationwide referendum on the introduction of a basic income on Sunday.

The proposal, if passed, would give every adult legally resident in Switzerland an unconditional income of 2,500 Swiss francs (£1,755; $2,555) a month, whether they work or not.

Supporters point to the fact that 21st-Century work is increasingly automated, with more and more traditional jobs, in factories, retail and even in finance and accounting, being done by machines. And they do not need salaries.

The campaign has staged some eyecatching demonstrations, including one in which hundreds of "robots" danced through the streets of Zurich, promising to "free" humans from the daily grind of Monday to Friday work, just to pay the bills.

"The robots are saying 'we don't want to grab your work and make you suffer'," said campaigner Che Wagner. "We want to make you free, that's why they want a basic income for us humans."

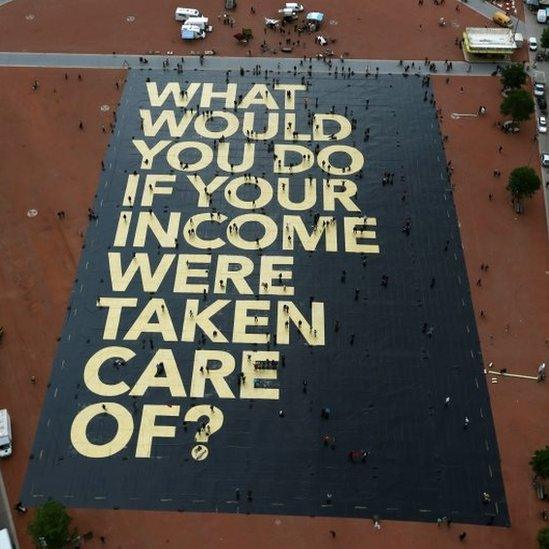

Supporters of a basic income last month crowdfunded a giant poster asking: "What would you do if your income were taken care of?"

Mr Wagner claims an unconditional income would be a fairer solution.

"In Switzerland for example, over half of all work that is done is unpaid - in the home, care, in the communities - so, that work would be more valued with a basic income."

Intelligent Machines: The jobs robots will steal first

What is artificial intelligence?

In fact the idea of a basic income is not new. In the 16th Century Thomas More suggested it in his famous work Utopia.

In the 20th Century economists from both the left and right argued that it could be a good idea.

There is little support among politicians for basic income - not a single parliamentary party has come out in favour

American economist Milton Friedman, who was a staunch proponent of free market capitalism, supported basic income because, he argued, it would allow what he called "a rag-bag of specific welfare programmes" to be abolished.

But despite all the debate, the idea of a basic income has never really caught on - until now, perhaps.

In Finland, the government is considering a trial to give basic income to about 8,000 people from low-income groups.

Different groups would be given different amounts, to try to find out whether more generous payments would deter people from seeking paid work.

Meanwhile the Dutch city of Utrecht is also developing a pilot project for basic income.

Around the world, many governments, from Australia to Canada, are taking a closer look at the administrative costs of running complex welfare systems and asking themselves whether a basic income would simply be cheaper.

Freedom to choose

Campaigners like Che Wagner are ideologically committed to the concept regardless of the cost, because they believe the current situation forces people into work they often do not enjoy, and which does not allow them to choose other activities they might enjoy more, and which could be equally useful to society.

Campaigners for a basic income say humans would be "freed" from the daily grind of Monday to Friday work

But Professor of Labour Relations Andy Stern believes increased automation, as illustrated by those dancing robots, is the most important reason for governments to think very seriously about basic income.

"Any good country needs to think about what's next," he told Swiss television.

"With a wave of technological change on its way, driverless cars, robotic surgery, the elimination of finance and accounting jobs, clearly there is going to be a huge disappearance of jobs.

"No one can really explain where the new jobs are coming from, so it would be foolish for a country not to prepare for what may be the greatest technological revolution in the history of the world."

Big questions

But there are many big questions over the Swiss proposal on basic income. For a start, although supporters have suggested a figure of 2,500 Swiss francs a month, they have offered no ideas on how that could be financed.

Opinion polls suggest voters are likely to reject the basic income proposal

Robots are far more efficient at doing repetitive jobs, basic income supporters argue

Instead, they say, if Swiss voters back the idea, Switzerland's parliament will have to work out how to implement it.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, there is little support among politicians for basic income: not a single parliamentary party has come out in favour.

But what is a surprise is that none of the political parties have cited cost as their main objection. Instead, there are concerns about encouraging a "lack of initiative and personal responsibility", and of not providing young people with a real incentive to find work.

Business leaders, already facing a skills shortage in many areas, are also alarmed.

But a key argument against basic income, and the one likely to sway many Swiss voters, comes from the right-wing Swiss People's Party (SVP).

Switzerland could easily afford to introduce a basic income, argues SVP representative Luzi Stamm, but not when Switzerland has a free movement of people agreement with all 28 EU member states, many of whom have a far lower standard of living.

"Theoretically if Switzerland were an island [basic income] would be possible," he said.

"You could cut down on existing social payments and instead pay a certain amount of money to every individual.

"But with open borders it's a total impossibility. If you would offer every individual a Swiss amount of money you would have billions of people who would try to move into Switzerland."

Like all European countries, immigration is a hot political topic in Switzerland. And the Swiss may be nervous about measures which could make their country more attractive than its neighbours.

Latest opinion polls suggest voters will reject basic income.

But the campaign has created a lively debate about how people will live, and work, in the future, and for Che Wagner that is already a victory.

"If you look back 20 years we will [ask] ourselves: why didn't we come up with this concept of a basic income earlier?" he said.

"It detaches work and income on an existential basis. It's great that we have fewer jobs, so that people can actually do what they want. We just want to make capitalism better and work in a more human way."

- Published16 December 2015

- Published31 July 2015

- Published31 July 2015

- Published15 May 2014

- Published18 December 2013