Auschwitz SS trial: Will Hanning case be Germany’s last?

- Published

To sit in the hushed makeshift courtroom where Reinhold Hanning is on trial is to watch Germany confront its past, face to face.

On Friday the court is expected to deliver its verdict on the former Auschwitz SS guard accused of complicity in the murder of at least 170,000 people.

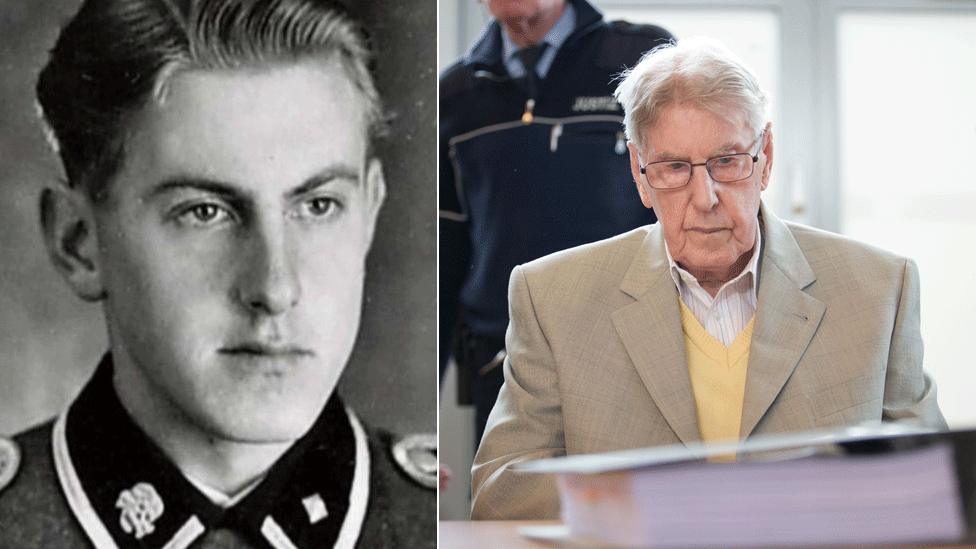

It's hard to imagine this frail 94-year-old man proudly dressed in his Nazi uniform, guarding terrified prisoners in a death camp.

But as, one by one, the elderly survivors of Auschwitz stand up and address him directly, that changes. Their voices are steady, their stories terrible. And the sights and sounds they describe resonate long after they've finished speaking.

And that's exactly what this trial is for.

The case in detail

Among the survivors to give evidence were Hedy Bohm, Leon Schwarzbaum (C) and Max Eisen

Reinhold Hanning denies complicity in more than 170,000 murders at Auschwitz

Prosecutors argue he contributed to the "aim of extermination"

Reinhold Hanning apologised, but survivor Leon Schwarzbaum said: "I lost 35 family members, how can you apologise for that?''

More than 1.1 million people were murdered at Auschwitz, most of them Jews

Of course this case is about determining one man's guilt or innocence, and establishing the significance of his part in the machine which systematically murdered millions of people.

In recent years, two other death camp guards have been convicted of helping to facilitate genocide. And prosecutors are racing against time to bring others to trial.

But this is really about Germany examining its darkest hour in public and officially recording, possibly for the last time, what happened. The survivors cannot prove Reinhold Hanning was there. But their presence at the trial, their voice, is considered crucial.

The Auschwitz survivor

Auschwitz survivor Hedy Bohm describes the moment she was separated from her mother shortly after arriving at the death camp

Hedy Bohm remembers, in vivid detail, her arrival at Auschwitz.

"I wish I couldn't but I do," she says. "It's not something you could erase from your mind.

"The shouting, the screaming, the crying, the children, the orders, the dogs barking… and in the background these fenced-in huge enclosures with these buildings. Where was I? What was this? Nothing I could make sense of."

Hedy was separated from her father and mother. She never saw them again. She was 14.

"I thought my mum would make it and when it's over we'd be together again.

"I didn't know; not in Auschwitz and in all the months when we worked in factories as slave labour; I didn't know about the crematoria; I didn't know the road my mother took and all those other mothers and children and babies, that it was going straight to be given poisoned gas and burned.

"I didn't know. I cannot forgive the men. I don't feel I have the right to forgive for having my mother and father killed and tens of thousands of children and babies. Who am I to forgive in their name? I don't have that right. But I have no anger. Thank God I have no anger."

Born in Auschwitz

Angela's mother Vera (L) gave birth to her in December 1944 after she was subjected to experiments by Josef Mengele

Angela Orosz-Richt never allowed her family to throw away potato peelings, insisting they ate them instead. Because in Auschwitz they saved her mother's life. And hers.

Angela's mother was pregnant when she was transported to the death camp. She managed to sustain the pregnancy by eating scraps from the kitchen where she worked. And she endured experiments - in utero - at the hands of the notorious Dr Josef Mengele.

"All my mother's life... she was trying to put it at the back of her mind" - Angela Orosz-Richt, Auschwitz survivor

"She became his guinea pig. One day she got an injection in her cervix. And the pregnancy - me - went to the left side. The next day she got another injection and I went to the other side. And that's what he played. He moved me with an injection. Then after a while, luckily, he forgot about her."

Angela was born on an icy December afternoon in 1944, hidden away on a top bunk in a women's accommodation block.

Just a few hours later, she says, her mother had to stand in a line, barefoot, for a three-hour roll call, terrified her new-born baby would be discovered or attacked by the hungry rats that plagued the camp.

For the rest of her life, Angela says, her mother had nightmares about her experiences in the camp. "When she was dying they gave her morphine but still she was saying 'Mengele is at the door, he is coming to get me!'

"We were holding her hand but Mengele was there."

More on the victims of Josef Mengele: The twins of Auschwitz

The Nazi Hunter

'Nazi hunter' Jens Rommel: "It's important for society to understand what happened in the concentration camps"

Water pipes gurgle worryingly in the hushed, gloomy room which is home to part of Germany's national archive. The air is papery and sweet. Uniform, grey paper boxes, each stamped with a black reference number, are stacked floor to ceiling.

These boxes contain files, details, the story of the darkest period in German history. And it is by painstakingly combing through them that Jens Rommel finds the clues that help him track down surviving Nazis such as Reinhold Hanning.

He finds their names typed on Nazi work records, scrawled in diaries or mentioned as witnesses in earlier trials of higher-ranking Nazis.

Those who ordered the atrocities are long dead. Many were never brought to justice, partly because, for a long time, the German authorities were reluctant to confront the past. Jens looks for junior, younger officers. If they're still alive, they're now in their nineties.

Last year, another former Auschwitz guard, Oskar Groening, was convicted of being an accessory to the murder of 300,000 Jews

'Auschwitz book-keeper' Oskar Groening sentenced to four years

"We have to try to do what's possible today," he says. "It's important for society in Germany and abroad to understand what happened in the camps, how it was organised and who was responsible. Not just the higher ranks but the lower ranks were necessary so that the machine could function."

There's been a shift in the way Germany deals with these people. In the past they were not deemed culpable; they were merely following orders. But in recent years, two former death-camp guards have been found guilty of helping to facilitate mass murder simply by working at the camps, by being part of the Nazi machine.

In 10 years' time there will be no-one left alive to prosecute. Reinhold Hanning's case is one of nearly 60 that Jens and his team have handed over to prosecutors in the past three years. But they are running out of time. He admits to a sense of frustration.

"I can't change what's been done or omitted in the past. Another 10 years and we could have done more."

- Published29 April 2016