Brexit: The view from the Reichstag

- Published

"You're in one of the most modern parliament houses on earth," the Reichstag tour guide says, pointing at the debating chamber.

The tourists, delighted, peer into the heart of the German Bundestag (parliament) and gaze up at the great sunlit glass dome above it, famously designed by Norman Foster.

What their smartphone photos don't capture, of course, is the political mood in the Bundestag. As MPs hold their final meetings before the summer recess, the shock and sadness at the Brexit vote has shifted - to frustration and anger.

Addressing reporters this week, the parliamentary leader of the Social Democrats (SPD), Thomas Oppermann, could barely contain his fury.

"David Cameron turned an internal conflict in his party into a conflict of society. In the end, he turned a divided party into a divided country. Demagogues like Johnson and Farage, in total irresponsibility, created chaos, lied to people, made promises they couldn't keep and now ran away into the undergrowth.

"We insist that the British clarify their position as soon as possible and start exit negotiations. We cannot give them any concessions because others will then demand the same."

Politicians here have watched in horror as Westminster fragments, and the cracks run, quicksilver fast, towards Germany.

More on Brexit:

The coalition government has bickered over how to respond to Britain. But what really divides them now is the EU. And how to reshape it without the UK.

In simple terms, the SPD wants further, deeper integration. And Angela Merkel's Conservative Party (CDU) wants to pursue a more flexible union where the remaining member states have more say.

Mrs Merkel's notoriously outspoken finance minister Wolfgang Schaeuble, who describes the referendum result as a "wake-up call", has proposed a European model which gives greater power to national governments.

"We must do everything to keep Europe together," says the CDU parliamentary leader Volker Kauder. "For that we need a common approach. I'm surprised that the SPD produces different proposals on a daily basis."

German Social democrat Thomas Oppermann believes David Cameron turned a divided party into a divided country

If that sounds like electioneering, that's because it is. Brexit has, in effect, fired the unofficial starting gun for next year's German general election.

Peter Beyer is one of Angela Merkel's Conservative MPs. The referendum result he says is of huge interest to his constituents who want to know what it means for Germany - and for Europe.

"If you look back, the different positions - for example, between austerity and spending - were there before. They were there with or without Brexit, but now it's brought them back into perspective. Brexit is a vehicle to again present to the Germans the two different concepts of Europe."

The EU will be a central - and perhaps now the only - election issue.

The right-wing Alternative for Germany party, chaired by Frauke Petry, did well in recent regional elections

The coalition has to address rising Euroscepticism (a phenomenon the SPD blame, in part, on CDU programmes of austerity) across the EU but also in Germany. A YouGov poll, taken one month before the British referendum, found that nearly one in three Germans would vote to leave the EU.

And then there's the right wing populist party Alternative for Germany (AfD). Its leaders want more power back in the hands of EU member states. And its anti-immigrant, anti-Islam and anti-Euro approach has won it support.

If the general election were held tomorrow, pollsters estimate it would take 15% of the vote. There's a fear here that Brexit might give fresh momentum.

But, right at the top of the Reichstag, where sunlight flashes on a mirrored central column, the German visitors disagree.

Fred looks up from a display of sepia photographs. "People will see - as a result of Brexit - the advantages to being in the EU, and that's why parties like AfD will have less support."

Sonya glances at the other tourists on the walkway which spirals around the dome. "I don't think Euroscepticism will win the upper hand in Germany, not if this great European project doesn't threaten the individuality of member states."

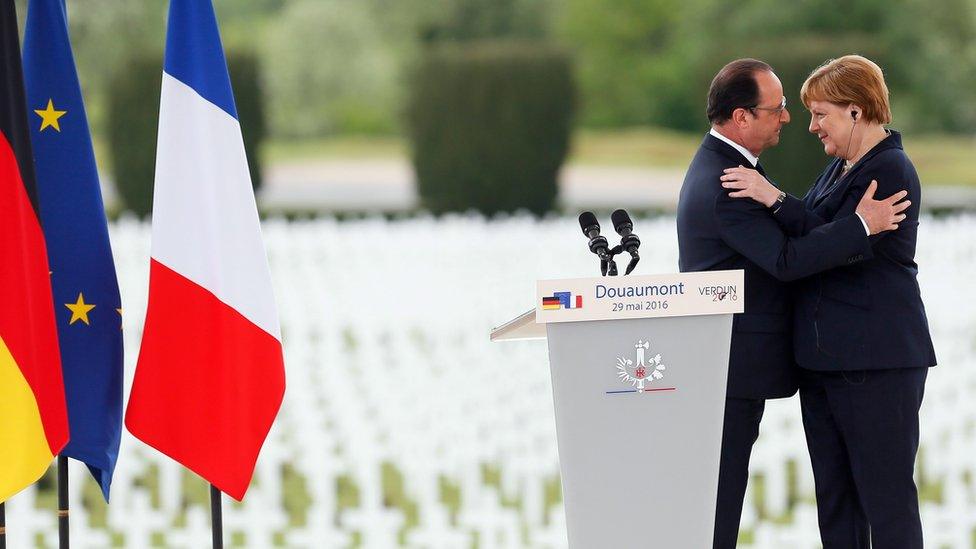

Will the Franco-German alliance be strong enough to lead a post-Brexit EU?

And in one of the Bundestag's many canteens, MPs gather to gossip. Brexit will undoubtedly change Germany's position within the EU. The UK has been a strong political ally, an important economic partner and a significant counterweight to Germany's clout within the union.

"The question for Germany now is with whom does it lead the EU?" says Daniela Schwarzer of the German Marshall Fund. "There's no danger it would try to lead it alone.

"The question is who are the allies to be partners in leadership? The Franco-German partnership is weakened. Germany has to get used to working with different constellations of allies. The different crises - the Eurozone, the migrant crisis - show it can't be the same partners every time."

Regardless of the political battle here in the heart of Berlin, what unites MPs is the desire to keep Europe together.

"I think it's the beginning of the end," says Jacqueline as she wipes the counter top and rearranges hotplates of schnitzel and vegetables. She was here, pouring coffees for shell-shocked MPs after the referendum result came in.

"People were really upset. And what does it mean? Imagine the British have a financial crisis - would we help them? I think they should rerun the referendum."

And - while few politicians here would echo her last point - there are many who hope that, as they leave for their summer vacations, they might come back to a different political atmosphere in the autumn. That, perhaps, Britain, with some breathing space, might yet change its mind.

- Published5 July 2016

- Published27 June 2016

- Published24 June 2016